What would you say about a company that had dozens, if not hundreds, of top strategic priorities? Where the proportion of major projects in jeopardy kept climbing and climbing, that got worse and worse at telling shareholders what exactly it was up to, where two thirds of department heads have been replaced over the past two years?

If you were being kind, you’d call it a shambles. But if you were talking about the British Government? It would just be business as usual.

One of the many striking aspects of the Trump administration is that it has deliberately staffed its Cabinet-level positions with “deconstructors” – people who not only believe that government is inefficient, but that the specific departments they are now overseeing are doing more harm than good. Their remit is not to make them work better, but to stop them working.

Here in statist old Britain, such thinking seems almost obscene. Yes, George Osborne swung his axe back in 2010, and kept swinging in 2015. But there was no sustained attempt to reconsider the basics of what government was doing, as opposed to how much it cost to do it.

This is surely barmy. As Dame Margaret Hodge pointed out in a recent piece for CapX, the state spends such astonishing amounts of our money that the issue of whether it’s doing so effectively should be an absolute priority for everyone interested in politics.

Today, the Institute for Government has published its annual Whitehall health-check. And this issue runs through it like the writing in a stick of rock.

Inevitably, the headlines will focus on Brexit – on the fact that the demands of negotiating the terms of departure, and refashioning British law to fit, will fall on a drastically shrunken workforce.

That will especially be the case in departments such as Defra which have little to no experience with shepherding primary legislation through Parliament, given that so much of what they do has consisted of enacting rules already agreed on in Brussels.

But that shrinkage in the workforce reflects a bigger, and more positive, story.

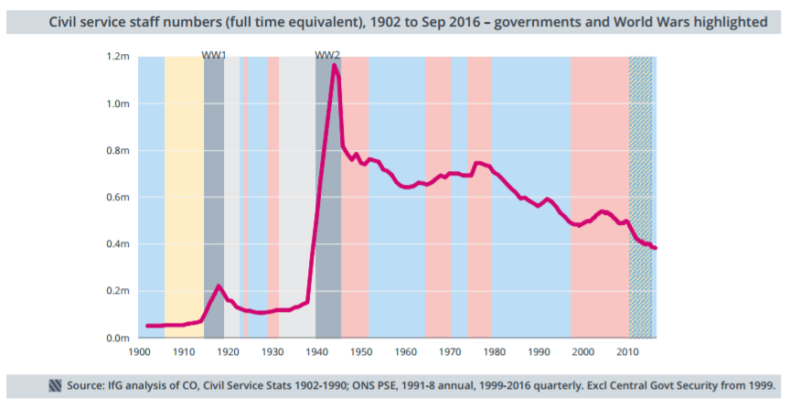

There is a line frequently trotted out – including in the IfG’s report, whose charts I’m using here – that the Civil Service is now the smallest since the Second World War.

What that fails to mention is that the same could be said of the vast majority of the years between 1980 and 2000, as well as every year since 2010.

As this chart shows, Britain really didn’t have much of a Civil Service before 1939. Afterwards, it had a huge one. But under Thatcher, Major and then Cameron, it was whittled away. The fall is even more dramatic when you consider that the chart shows Whitehall’s raw numbers, rather than its proportion of the growing population.

But it’s hard to argue that the economy, or the national fabric, suffered much if any damage in the process. The reverse, if anything.

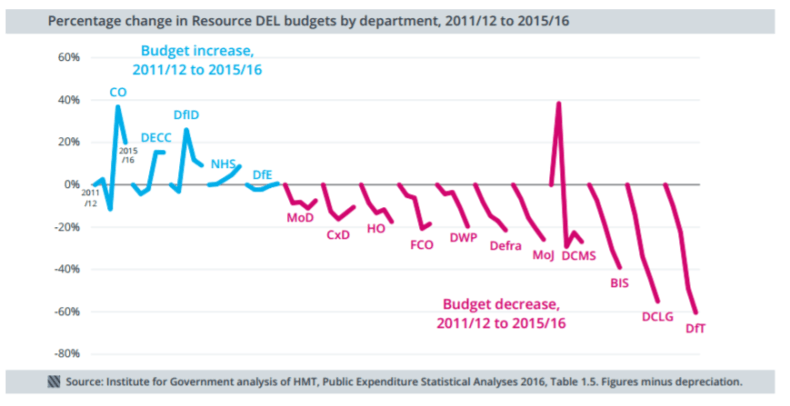

Yes, departmental budgets have shrunk in recent years.

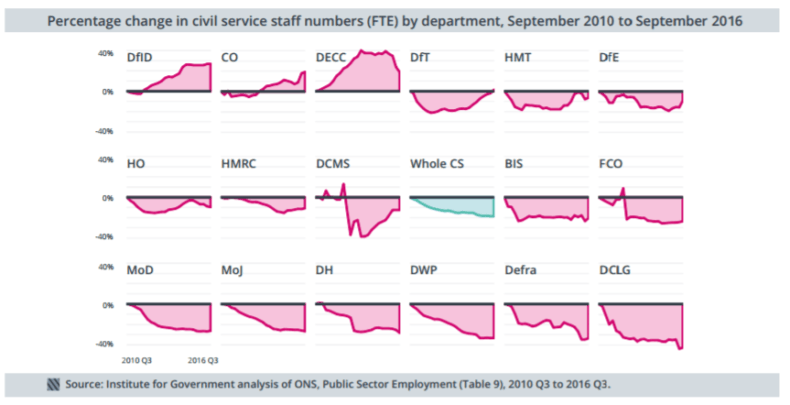

And the same is true of Whitehall’s staffing levels (at least in most of its many departments).

But it doesn’t seem to have affected morale. Between 2015 and 2016, even as the cuts continued, staff engagement in the vast majority of departments actually went up – the exception being the Department of Health, which as the report’s authors point out may owe something to a round of redundancies there.

In other words, just like everywhere else, it is not the quantity of employees that makes for good government, but their quality and productivity.

Many of those lost civil servants now appear to be the bureaucratic equivalent of typists or coal miners – people whose skills and necessity were superseded by technological advancement. HMRC, for example, no longer needs thousands of people to manually enter tax information, when we can all submit self-assessment forms online.

But even as it has cut its scope, Whitehall has still not limited its vision. The leviathan state has been put on a diet, but its ambitions and preoccupations remain as sprawling as ever.

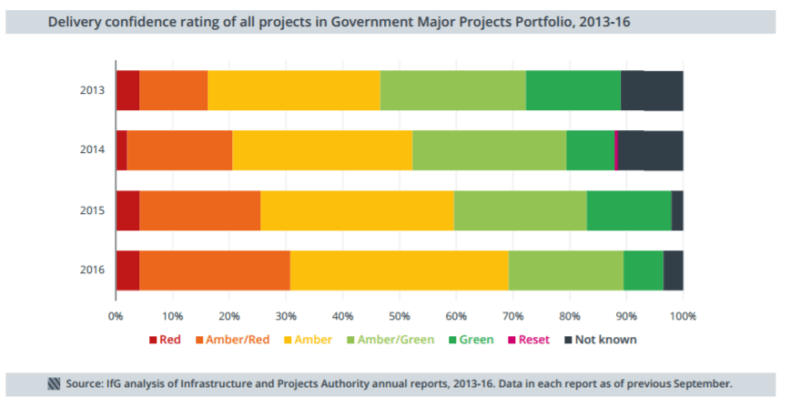

When he was appointed, the new chief executive of the Civil Service, John Manzoni, said that the government was “doing 30 per cent too much to do it all well”. Since 2013, the number of “major projects” the Government is pursuing has indeed fallen – but not by as much as Manzoni hoped.

At a conference I attended recently, Sir Jeremy Heywood, the actual head of the Civil Service (it’s confusing, I know), said that Whitehall has “nothing to learn” from the private sector in terms of project management.

Have just checked the tape for #IFGCabSecs event and @HeadUKCivServ really did say this. Hostage to fortune to say the least… pic.twitter.com/SRfesP47K8

— Robert Colvile (@rcolvile) November 30, 2016

Yet despite this boast, an ever-increasing proportion of them are coded as amber or amber/red, meaning that they are in danger of running into trouble – probably because there are still just too damn many.

The wider problem, however, is not just with those major projects – the Crossrails and aircraft carriers and Universal Credits – but with the basic structure of Whitehall.

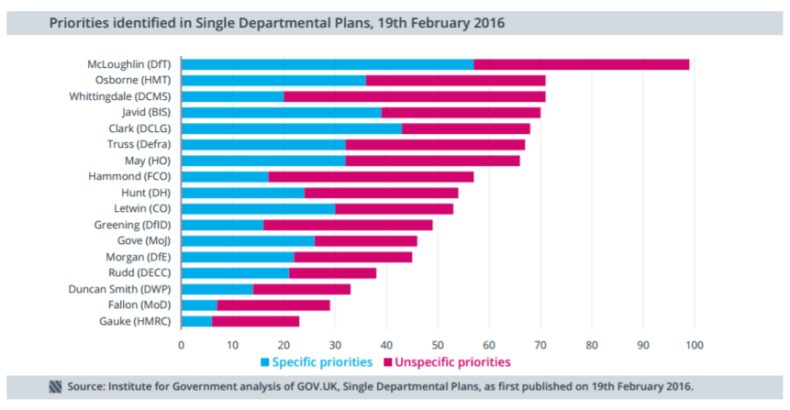

In their strategic departmental plans. every senior minister has set out between five and 50 “specific priorities”, and several times as many “unspecific priorities”. The idea behind the plans was to focus Whitehall on its key priorities. But as the IfG observes, they’ve become not a focused set of must-dos but “little more than a laundry list of nice-to-haves”.

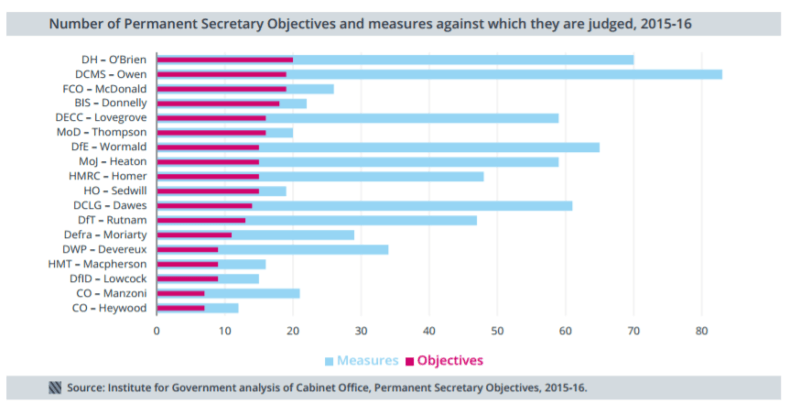

It gets worse. In the single year between 2014-15 and 2015-16, the average number of key objectives for the permanent secretaries, who actually run the departments on ministers’ behalf, rose from nine to 14. And the average number of performance measures against which these would be assessed more than doubled, from 15 to 39. Oh, and only six of those permanent secretaries had remained in post since the 2015 election, meaning that there was nothing resembling continuity in their implementation.

It’s always harder for government than for businesses to focus, laser-like, on a few specific goals. Each department is laden down with a host of statutory functions and commitments: you can’t tell farmers you’re not processing their EU grants because you really want to get woodlands sorted.

But this chaos of objectives and targets, of sudden shifts in strategy and personnel, hardly suggests an organisation that is focused, above all, on Getting Stuff Done. Take the objectives for Chris Wormald at the Department for Education – most sound entirely unexceptionable (apart from the platitudes about “the DfE way of doing things”).

But I counted 65 separate major priorities, listed in a way that put having “a well-attended series of induction and welcome events” at the department’s new offices on the same level as revising the national schools funding formula or speeding up the rate of adoptions.

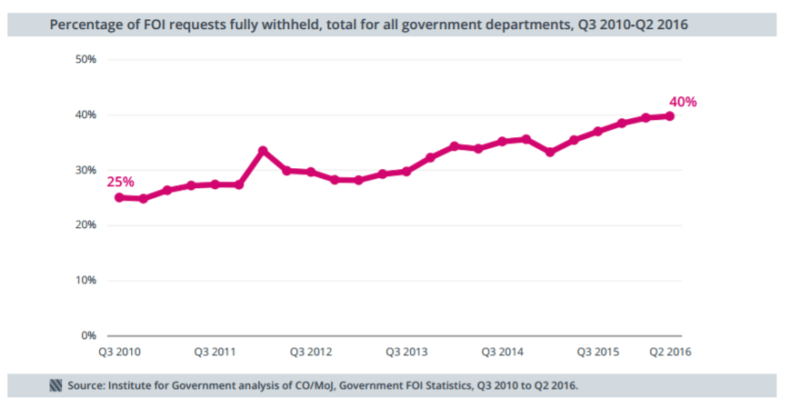

And at the same time as it is trying to do too much, government is becoming worse about letting others hold its feet to the fire. Year after year, fewer and fewer Freedom of Information requests are being answered – and details of departmental spending are being released in a notably dilatory fashion. There is nothing a bureaucracy likes less, after all, than having its feet held to the fire.

You don’t have to be a paid-up Trumpkin, in other words, to see that the British state could benefit from some clearer strategic thinking.

Over the coming years, the added pressure of Brexit may indeed put so much additional strain on the Civil Service that it cracks.

But it may also teach Whitehall a valuable and long-overdue lesson about priorities – and, in the process, lead to a better balance in its functions and priorities between the pointless, the desirable and the actually necessary.