Eurasia is emerging as a distinct entity with great economic and strategic significance. Stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east, the vast region covers 35 per cent of the earth’s surface and is home to five billion people, living in over 90 different countries and producing 65 per cent of global GDP.

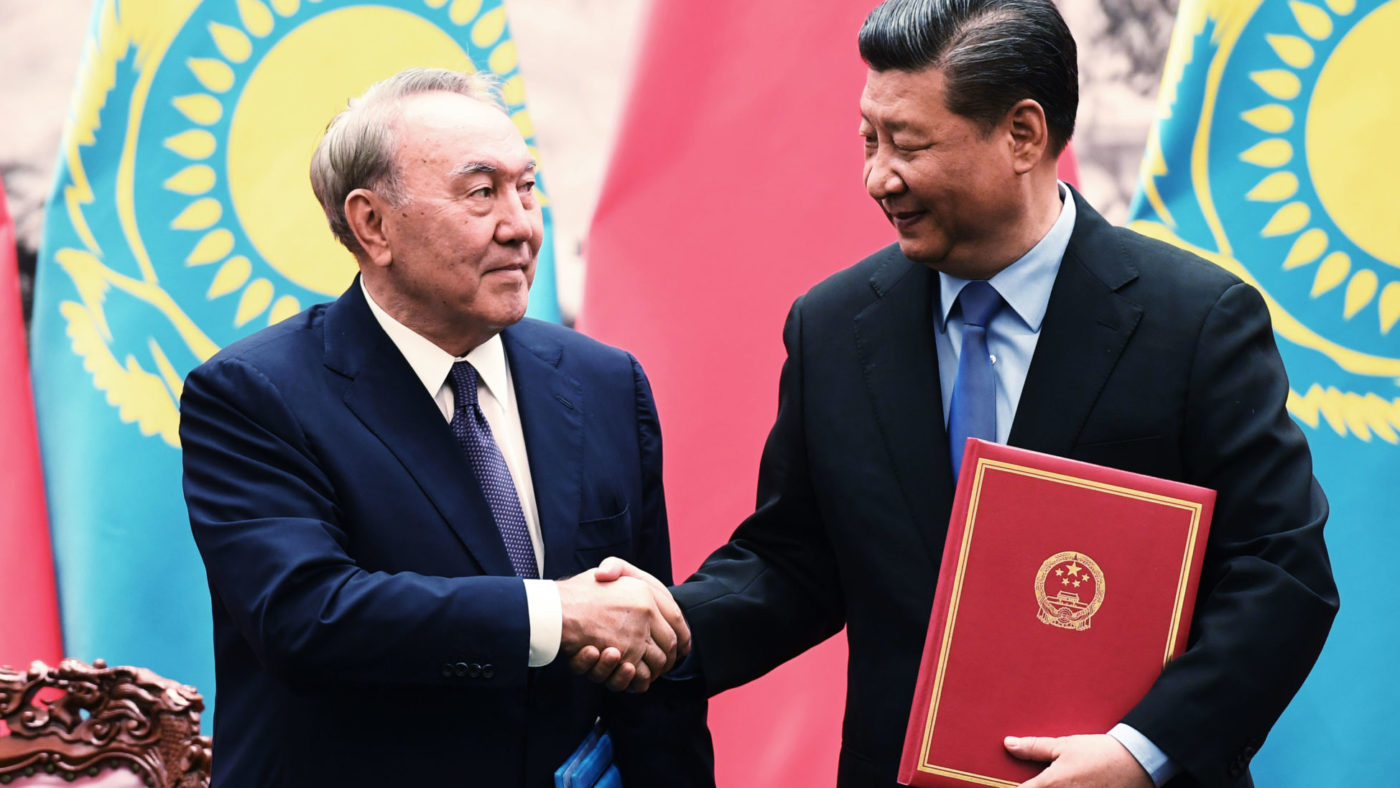

As early as 2007, Donald Trump was quick to identify Eurasia’s potential and trademarked the Trump brand in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Armenia. In 2012, he sought to trademark his name for hotels and real estate in countries across the spine of the Silk Roads, including Iran and Georgia. More recently, China has invested heavily in the region through the Belt and Road Initiative, which was launched in 2013.

Russia is also thinking in Eurasian terms, spearheading the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union in 2014. According to World Bank and OECD data, not one of the ten fastest-growing economies in 2017 was located in the western hemisphere, nor has one been for the last decade – Uzbekistan is now the world’s second fastest-growing economy. But why is Eurasia on the rise?

In his new book The New Silk Roads: The Present and Future of the World, which was released last week, Peter Frankopan explores Eurasia’s growth and role as a key player in a new world order. The Professor of Global History at Oxford University is also the author of The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, which was published in 2015. As he sat down trying to write an additional chapter to the new edition of his 2015 book, he realised that too much had happened and that a chapter would not be enough to cover the events since then and their impact, hence The New Silk Roads. The overarching theme is how the increasingly isolated and fragmented West stands in sharp contrast to the countries along the Silk Roads, where ties have been strengthened and mutual cooperation established – albeit not without big challenges.

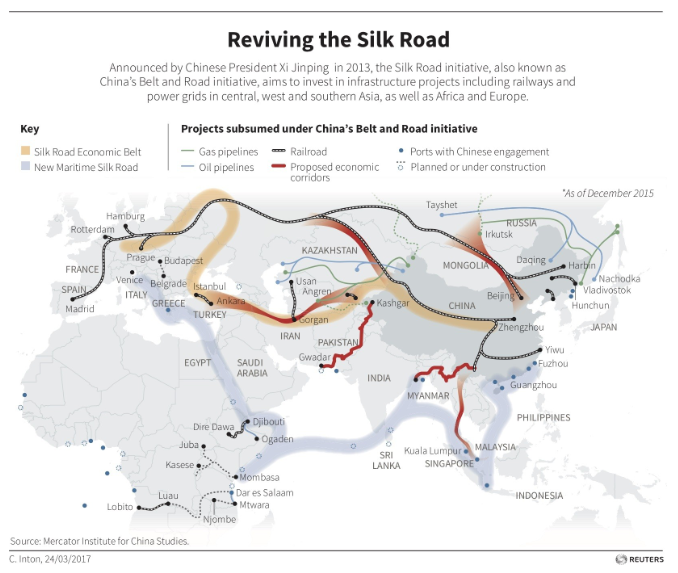

The Silk Roads were historically an ancient network of trade routes, formally established during the Han Dynasty of China, which formed commercial links between distant regions. Westerners brought horses, animal furs and skins, honey, grapes, gold, silver and slaves to the east; people from the east brought tea, spice, porcelain, silk, gunpowder, bronze, ivory and rice, among other things. As trade came to rely more on shipping, however, land routes fell out of favour and many Eurasian hubs floundered.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is explicitly resigned to re-connect the countries along the Silk Roads. And it seems to be working, with Chinese trade with countries along the Belt and Road up almost 18 per cent year-on-year in January 2018. The initiative – in reality a collection of different projects – aims to improve trading and transport links between China and the world, mostly through infrastructure investments.

The scale of the project is enormous. So far, China has paid over $900 billion in loans to 71 countries and many projects are already underway. Kazakhstan has opened a dry port on its eastern border with China. Its seaports on the Caspian sea are expanding and the east-west rail and road connections are being upgraded. On the other side of the Caspian, Azerbaijan and Georgia hope to capture some of the flow of Chinese goods to Europe via the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway and Georgia has secured $50m in Chinese investment in a proposed deep-sea port on the Black Sea.

While many of the countries benefiting from the BRI are in dire need of infrastructure and modernisation, there are plenty of risks in becoming too reliant on China – and there are still challenges that are not being addressed, as Frankopan points out.

Water is a particular concern across Central Asia, where many countries are landlocked. This is illustrated by the near-disappearance of the Aral Sea since 1967, when the rivers that fed it were diverted to support misguided Soviet agricultural initiatives. It is estimated that around 70 per cent of developmental problems in Central Asia are caused by fresh water shortages. Frankopan also links the water issue to the uprisings that took place in Iran earlier this year where 97 per cent of the country was to some degree experiencing drought.

There is also the problem of radicalisation in the region. The instability in Afghanistan and the significant numbers of ISIS supporters with Central Asian backgrounds fighting in Syria and Iraq are a cause for concern not just for the region, but the world. The terror attacks committed in New York, Stockholm, St Petersburg and Istanbul in 2017 were all perpetrated by men from Central Asia and many fear that China’s BRI investments will risk breeding further unrest and extremism.

The BRI is mainly a result of China’s economic transition from manufacturing to services and, because of that, the country has a lot of excess steel and metals they want to export, for which they need infrastructure to be put in place. There is also a large workforce that needs to be employed.

Therefore, China supplies all the workers to carry out the projects included in the initiative, which not only limits the scope for local involvement but also creates tensions with the younger host-country populations, who must now compete for employment opportunities. Frankopan argues that there is a real risk that the BRI will end up creating infrastructure networks for extreme and radicalised organisations in unstable countries.

In Kazakhstan for instance, China’s policies brought the masses out to stage nationwide protests in 2016, when the Kazakh government announced a land reform. These unprecedented demonstrations in the relatively stable Kazakhstan were partly driven by popular mistrust toward the Chinese companies and a culture of corruption in the Kazakh state.

Talking about the BRI at a forum in Beijing in May 2017, President Xi Jinping said: “We should foster a new type of international relations featuring win-win cooperation.” China’s benefits are clear: the initiative helps secure its energy supply, facilitates China’s economic transition and creates future business opportunities by using infrastructure to increase disposable wealth and demand for goods that Chinese businesses are able to supply. And the economic benefits of a new motorway, railway or port for the hospitality, industrial or retail sectors for the countries at the receiving end seem clear enough. But is it really a win-win situation?

Using a Chinese-only labour force can not only aggravate tensions and breed radicalisation but it also enables Chinese companies to do well at the expense of others. While it may not be in China’s interest to encourage extremism – Beijing is well aware that it needs secure and stable neighbours, especially at the border of its troubled western autonomous region of Xinjiang – the Communist Party is playing both sides and has invited several leading members of the Taliban to the capital to discuss projects.

The economic advantages are not as clear cut as they seem either. Transit countries are likely to keep trade tariffs to a minimum to stop China using different, cheaper routes for its goods, which would limit their opportunities to raise revenue. If the returns on the BRI investment prove underwhelming, they could struggle to repay China’s loans and to pay for maintenance, with soured bilateral relations as a consequence.

The investments have also exacerbated the widespread issue of corruption in the region. Corruption is an endemic vice in the Communist Party’s totalitarian political framework and the problem is only increased along the Silk Roads as Beijing engages corruption-ridden countries where democratic institutions are weak or nonexistent. In many Central Asian states, local elites have been lining their own pockets while burdening the wider population with debts that they cannot hope to pay back.

In the escalating trade dispute between Washington and Beijing, Eurasia, however, stands to benefit. Since January, Trump has been ramping up import duties on goods from China. After tariffs on $34 billion worth of Chinese goods officially took effect in July, China imposed equivalent retaliatory import duties on the US. Meanwhile, China has found alternatives in Central Asia. After no longer importing American soybeans for example, it linked a deal with a supplier in northern Kazakhstan to buy 100 tons. Kazakhstan also announced it would triple its supply of wheat to China by 2020 over 2016 levels.

And what about Russia? The contrast between Moscow’s modest regional capability and China’s multi-continental ambition begs the question: what happens if both autonomously and organically come to two different visions of Eurasia?

Russian officials have continuously warned members of the Eurasian Economic Union that they should be more cautious with China and that they would be better off negotiating with China in the framework of the EEU, which Russia dominates. But this advice largely falls on deaf ears. China’s financial clout and infrastructure-building capacity are irresistible for investment-hungry Central Asian states. While they have to be mindful of Russia’s sensitivities, Moscow cannot offer them much in terms of modernisation.

The Belt and Road Initiative harbours an extraordinary transformative capacity, but the risks that comes with it might mean that these modern Silk Roads end up being less renowned for the spread of prosperity than its predecessor. But the fact remains that the countries along these roads are rising. And, as Frankopan concludes, “They will continue to do so. How they develop, evolve and change will shape the world of the future, for good and for bad. Because the Silk Roads have always done just that.”