One of the interesting things about polling is that it provides opportunities to test which stereotypes about the views of different groups hold true in reality, and which are just lazy assumptions.

Coffee consumption seems to be one area prone to such pigeonholing. American political debate has long had the pejorative “latte liberal” tag. And in the UK, the flat white has sometimes been derided as “hipster coffee”, or at the very least assumed to be the choice of trendy, young urbanites – a demographics who might also fit the stereotype of Jeremy Corbyn’s base.

But are characterisations like these accurate? We asked the public what drinks they like, to see if there actually were any patterns. The question asked people to choose up to three drinks that they might find in a café, that they drink regularly.

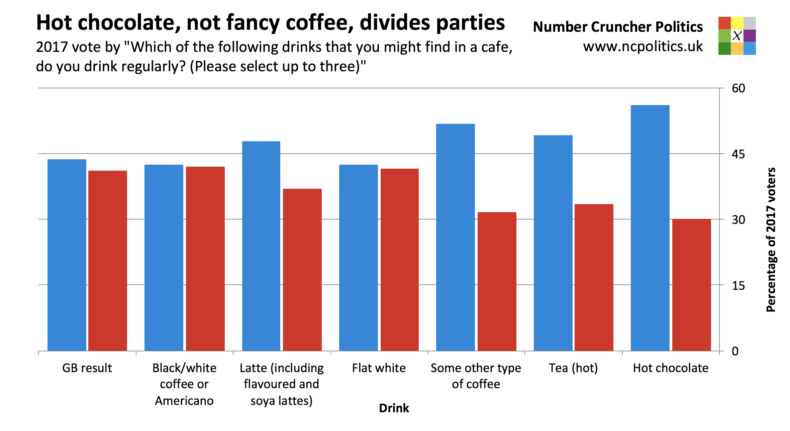

It turns out that most of the stereotypes around who prefers what type of drink are not backed up by the data. Flat white consumption isn’t in fact a predictor of voting at all – flat white drinkers narrowly voted Conservative in 2017, just like everyone else.

The more traditional black or white coffee or Americano doesn’t seem to signal traditional views – its drinkers were slightly less Tory than the electorate as a whole, and among them the two main parties were each on 42 per cent of the vote at the last election.

The most divisive drink in Britain, it seems, is hot chocolate. Because the cup of cocoa is substantially more popular among older people, the Conservatives secured 55 per cent of the vote among hot chocolate drinkers in 2017, to Labour’s 30 per cent.

The general election was closer than that among tea drinkers, but would still have produced a 16- point Tory lead and a landslide majority if only they had voted.

In terms of overall popularity, tea and the traditional coffee were tied on 34 per cent each, and were first and second in most of the crossbreaks, ahead of lattes (including flavoured lattes) on 23 per cent, hot chocolates on 15 per cent and flat whites on 11 per cent. The numbers add up to more than 100 because many people selected more than one hot drink.

But what about the patterns at aggregate level, looking at trends by geography? Unfortunately we don’t have data on how much or which types of coffee are consumed by area, but we can look at where the cafés are.

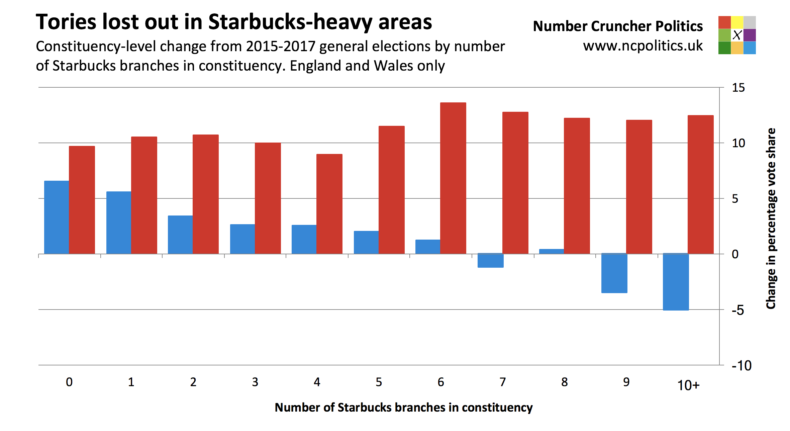

Thankfully it’s fairly easy to obtain addresses for every Starbucks in Britain, which can then be matched to and tallied by Westminster constituency. And if we then zoom out and look at general election results – specifically the change in vote share between 2015 and 2017 – we can observe a very interesting pattern.

In England and Wales, The Conservative vote increased by seven points in constituencies with no Starbucks branch, but fell 5 points in constituencies with 10 or more branches. The Labour vote had no such pattern – it went up about 10 points across all levels of Starbucks density. There was no such pattern for either party in Scotland.

This finding is a clear example of correlation not equalling causation. The Conservatives would not win a majority simply by demolishing branches of Starbucks. And conversely, for those wishing the Seattle-based coffee chain were better represented in their locality, voting Labour wouldn’t make the green siren magically appear.

The pattern is, in all likelihood, because Starbucks cafes tend to be concentrated in areas with lots of younger professionals and university graduates (and by extension, Remain voters). Each of these groups swung heavily against the Tories in 2017. The presence or absence of cafés and the switching of voters between different parties are unrelated to each other, but are both related to the incidence of the aforementioned pro-EU demographics.

It is also a potential an example of what’s known as the ecological fallacy, where the nature of groups can lead to misleading inferences about the behaviour of individuals within those groups. We can say that areas with lots of Starbucks branches voted Remain in 2016 and swung to the left in 2017. But without further information, we can’t reliably conclude that Starbucks customers opposed Brexit or that they backed David Cameron but not Theresa May.

What we can conclude is that political stereotypes are often very misleading. Pigeonholing coffee drinking habits is (probably) harmless enough, but the danger is that this sort of thinking – based on preconceptions rather than evidence – occurs in areas where wrong assumptions can lead to bad politics and bad policy.