Earlier this month South Africa held its sixth parliamentary election since the birth of multi-racial democracy in 1994.

Together with its two satellite organisations, the South African Communist Party and the Congress of South African Trade Unions, the African National Congress has won yet another term in office and will extend its rule over South Africa until at least 2024. The main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, has lost some electoral ground against the ANC coalition, with most of the disaffected voters going to a Maoist political group known as the Economic Freedom Fighters.

What does the election outcome mean for the future of the country?

According to the final election results, the ANC’s share of the vote declined from 62.15 per cent in 2014 to 57.5 per cent in 2019. The DA’s share declined from 22.23 per cent to 20.77 per cent. The EFF grew from 6.35 per cent to 10.79 per cent. The Afrikaner-focused Freedom Front Plus grew from 0.9 per cent to 2.38 per cent. The Zulu-focused Inkatha Freedom Party, which is still led by the 90-year-old Mangosuthu Buthelezi, grew from 2.4 per cent to 3.4 per cent.

As such, South Africa’s political spectrum now consists of the EFF on the far left, the ANC on the left, the DA on the centre-left, and the IFP and the FF+ on the centre right.

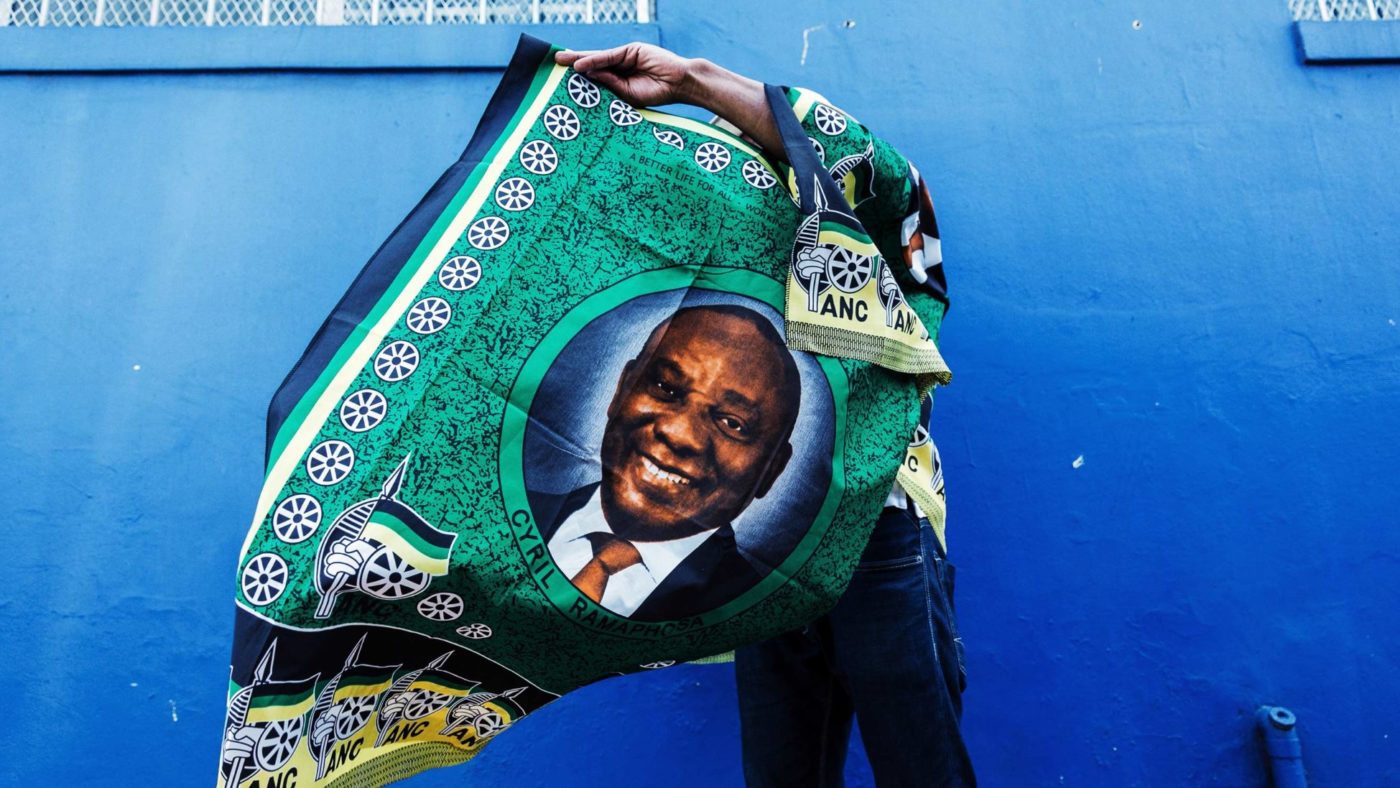

How are these results to be interpreted? First, the ANC avoided much of the electoral punishment by jettisoning its corrupt and discredited former leader, Jacob Zuma, and preventing his ex-wife, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, from replacing him. Instead, it chose as its leader the affable former Deputy President, Cyril Ramaphosa, who has mastered the art of speaking from both sides of his mouth – reassuring international financial investors of safety of their investment and, at the same time, promising his voters that the ANC will expropriate private property without compensation.

The hapless leader of the DA, Mmusi Maimane, in the meantime, abandoned much of his party’s liberal commitment to non-racialism by embracing many of the ANC’s policies, including affirmative action and race-based economic redistribution known as Black Economic Empowerment (BEE). That, he hoped, would make him popular with the black voters the DA needs in order to make further electoral gains. In the event, the DA’s black vote rose from 4.3 per cent in 2014 to 4.7 per cent in 2019. Many white voters, in the meantime, abandoned the DA for the FF+.

What might the ANC accomplish over the next five years?

Let’s start with the admittedly short list of good policy proposals. Ramaphosa has promised to relax the moratorium on oil and gas exploration, exempt mining prospecting from BEE demands, require voting before strike action and, possibly, allow the future use of coal for electricity generation. These are small, but welcome nods in the direction of economic reality that could improve South Africa’s anaemic growth rate.

The list of potentially harmful policy proposals is much longer. The most damaging is the proposed constitutional amendment allowing for expropriation without compensation (EWC). The exact wording of the amendment will be crucial, though harm to property rights will also be caused by new regulations allowing the government to set the worth of properties seized under eminent domain at zero.

That will amount to EWC in all but name. The Copyright Amendment Bill, which provides for the expropriation of intellectual property, is awaiting Ramaphosa’s signature and new regulations allowing the government to override patent rights over medical drugs is being drafted.

The recently-signed Competition Amendment Bill increases the government’s regulatory powers over the private sector. The new Conduct of Financial Institutions Bill increases government oversight over financial institutions and the Financial Matters Amendment Bill does the same with regard to auditing firms. In addition to the new national minimum wage, there will be a carbon tax. The BEE and employment equity requirements, which aim at racial representatively across the board swathes of the economy, will be made more burdensome. Such policies are likely to worsen the unemployment rate that is currently running at over 27 percent.

The nationalisation of the South African Reserve Bank is on the government’s agenda. The same goes for the health sector. The Medical Schemes Amendment Bill will prevent private health insurance companies from offering different benefit options in order to facilitate the creation of a state-run medical aid plan. The end goal of the government is the South African version of the British NHS. The government will also increase its imprint on the education system by reducing the autonomy of school governing bodies. Finally, the government’s also thinking of forcing private savers to fund government projects, including bailouts for South Africa’s ailing state-owned enterprises.

Since 1994, roughly 70 per cent of the South African electorate has consistently voted for parties committed to socialism or communism. South Africa’s pathetic economic performance over the last decade or so is a direct result of the slow strangulation of the economy by the ANC government.

Unfortunately, as has been the case throughout most of Africa since independence, socialist failures have not resulted in soul-searching and a change of tack. On the contrary, they have led to an even warmer embrace of socialism and eventual economic collapse. Whilst miracles do occasionally happen, seeing the distribution of political forces after the 2019 election, it is difficult to be optimistic about the future of the Rainbow Nation.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.