Imagine being on an island where more than one in five people have never heard of Cambridge Analytica, gammon is an old-fashion pork cut, 78 per cent of people don’t talk about politics most days, and 99 per cent of people don’t watch Prime Minister’s Questions.

In fact that island exists, and you may well be on it now. It’s called Great Britain. It may be clichéd to talk about a Westminster Bubble, obsessed with parochial news stories that the public simply doesn’t care about. But some clichés are true.

Take the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica row. For weeks this story occupied the news, and political Twitter. It would be difficult to go near either, at any point during that period, without hearing the story or the fierce debate that it prompted.

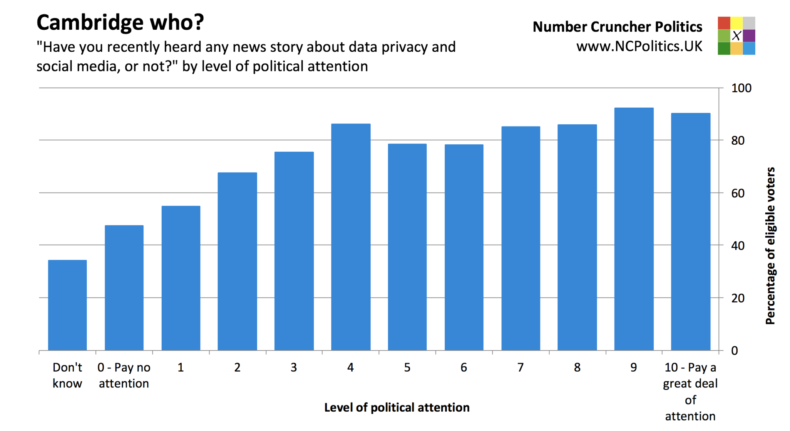

Yet when we asked the public, in polling conducted at the height of the scandal and published here for the first time, 21 per cent said they had not recently heard any news story about social media or data privacy. That’s equivalent to 10 million eligible voters not having heard anything about one of the biggest political stories of the year.

Even among those who rate their level of attention to politics as 10/10, almost one in ten hadn’t heard about this scandal.

In fact even these should be treated as minimum estimates, because some people “remember” hearing stories when in reality they haven’t. If you ask people a placebo question about a fictitious story bearing no relation to anything actually in the news, some people will say they heard about it.

Although social media is rarely itself the big story, it may have played a role in widening what I refer to as the “salience gap”. It’s well understood that people tend to follow others with similar opinions – it now seems that the same can be said of similar levels of political engagement.

Other polling, notably by Populus, routinely finds double digit percentages of respondents unable to name any news story each week.

But even if the public know about a story, do they care? Theresa May’s disastrous 2017 speech to the Conservative Party conference was covered extensively, and many politicos took to Twitter to describe it as an “epitaph” to her political career, while in reality it made almost no difference.

Likewise, Gordon Brown’s “open mic” denunciation of Gillian Duffy as a “bigot” shortly before the 2010 general election was a major story and suggested as a possible game-changer – yet it changed the game by, at most, fractions on a percentage point.

Another sub-type in this genre is the story that genuinely cuts through, and does move the polls, but only temporarily. To be worth paying attention to, a swing in the polls needs both to be real and sustained, and many moves fail on at least one of those criteria.

This can be because people change their minds, but only briefly, or because the news makes one party’s supporters much more enthusiastic and therefore keener to respond to a pollster’s phone calls or emails. This sometimes happens around ‘set piece’ events, such as budgets, major speeches and party conferences.

However it can also apply to news stories. During and after fuel crisis in 2000, polls showed that a substantial Labour lead had suddenly became a Tory lead. This episode had quite obviously caught the public’s attention – it had literally brought the country to a halt. And yet, just nine months later, Tony Blair won 413 seats and a majority second only to his 1997 landslide as the biggest for anyone since the war.

Yet another variation is where large moves, or unexpected results, are mis-attributed to things that were in fact of limited significance. Looking back through history, there are quite a few examples.

Scandals are a prime example. The Conservative sleaze scandals in 1994 are often cited as a factor in John Major’s 1997 drubbing, but by late 1993, Labour already had a 20-point lead, which was still about 20 points in mid 1994. The subsequent widening in Labour’s poll lead actually coincided with Tony Blair becoming leader, not with any scandal. Much as the sleaze was meat and drink to the press, the damage had already been done on black Wednesday.

Likewise, Major’s shock victory at the 1992 election. It wasn’t “The Sun Wot Won It” or Neil Kinnock’s exuberance at the Sheffield rally that lost it. The shock was due simply to the polls having been wrong the whole time, and not (at least, not primarily) the result of a late surge for the Tories.

The takeaway from all of this is that what is newsworthy in Westminster is almost always much less newsworthy outside it, and still less likely to be game-changing. Political news is generally consumed by political audiences. There is nothing wrong with that. But next you hear something that sounds like a major development, don’t simply assume the public know or care.