Today’s A level results will, rightly, be celebrated by the thousands of students who got the grades they need to go to university. This sounds platitudinous, the sort of throwaway statement a talking head might churn out before pivoting away from the mollifying bullshit to point out that A level grades have reached Weimar levels of inflation and that teachers have gamed the system, rendering the whole process empty and valueless. A levels, once the gold standard of assessment, have become a debased currency.

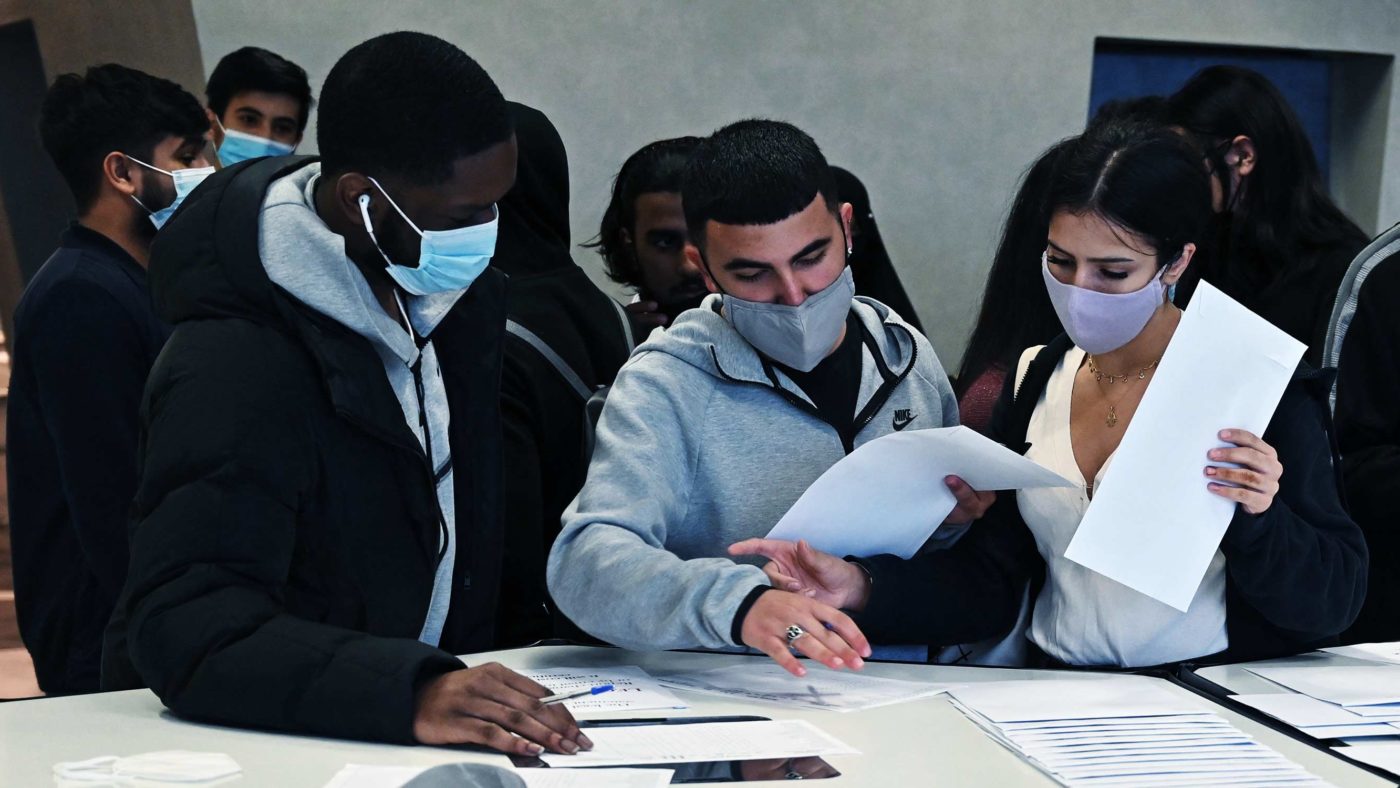

But celebrate those students should. And only those who have not been directly involved in schools since the pandemic began would resent teachers and students some fleeting moments of satisfaction in the August sunshine, before the rains of reality and recriminations return. It has been a difficult time, not just because of the additional workload resulting from the cancellation of examinations in January (requiring teachers taking on all the marking needed to determine Teachers Assessed Grades), but also because we have had to deal with endless confusion, obfuscation and policy changes from the Department for Education.

The inquests about this year’s results won’t be long in coming, and when the questions do begin to be asked they should be penetrating and demanding, so that we can avoid this ever happening again.

Why weren’t schools consulted last year about what they want to replace examinations? Contrary to what you might read on Twitter, the majority of secondary school teachers support public examinations and do not want to see them replaced with continuous assessment or coursework. Why were schools allowed to follow their own procedures, writing their own policies, and using their own sources of evidence, to arrive at the final grades? Only a fool or, more worryingly, the Chief Regulator of Ofqual, could have hoped these results would be fair and accurate across schools. Why were schools not given greater guidance from Ofqual and the Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ)? Why was there not a robust system of quality control, rather than the façade that we were asked to believe in (and which has resulted in less than 1% of grades being changed)? And finally, once the celebrations have finished and the Freshers’ Weeks begin to loom, we’ll have to ask how we arrived at a situation where nearly half of all grades awarded are A* or A?

This is policy failure on an epic scale. And when this happens in certain spheres, such as health or education, it very quickly moves from Whitehall spreadsheets and projections into changing the lives of thousands of people, their futures altered irrevocably. At a very human level, not only will universities struggle to cope with the sheer number of high grades they are now presented with, but they will also have to accommodate students with vastly different ranges of subject knowledge. Put bluntly, an A* in a non-selective school could be hugely different from an A* in a highly selective school. Teachers in both schools will only be able to establish grade boundaries, and equal distribution of grades, according to the students in front of them. The distortions will be unavoidable. Establishing consistency across those schools became impossible once the Government decided to not use an algorithm for standardisation. Fairness, at a systemic level, ended there. The upshot will be that students will be accepted onto courses they are not suited for, and many will not enjoy them, and will drop out.

At a more abstract, and less human level, when an assessment system is distorted so much it will take time to return to anything like normal (if that happens at all). What will be acceptable grades for next year’s GCSE and A level students? More pressingly, what should they be taught in under a month’s time? What examinations are they preparing for? How do you take the heat out of a system which now seems impossible to regulate? Those who should have the answers to such questions remain silent.

This crisis in schools has revealed a number of weaknesses in a system that was already struggling to accommodate endless policy initiatives, low morale, and changes to assessment. Firstly, examinations may be unloved by many but they remain the fairest and most objective way of measuring attainment. To think otherwise is a distraction from a wider, and more urgent debate about what our children should be taught to prepare them for the next stage of their lives; that may mean that fewer children are expected to go to university and pursue, instead, vocational qualifications.

Secondly, as Jeremy Yallop has already written for the Higher Education Policy Institute, Ofqual has, in abandoning its legal requirement to ensure reliability and consistency of qualifications, rendered itself obsolete. It has become too influenced by government, its positions inseparable from the Department for Education, and has lost its objectivity. Ofqual is no longer fit for purpose and should either be scrapped, or reformed so that it can actually return some robustness and fairness to our assessment system. It seems clear throughout the pandemic than it, and those who lead it, are incapable of doing so.

Lastly, of course, the fiasco that has seen such huge rises in A level grades (and, no doubt, GCSEs on Thursday) has its origins in the Department of Education. It is this department, shielded by Number 10, that has been responsible for a monumental dereliction of its duty of care to this nation’s children. Root-and-branch reform of the department is long overdue, and the only alternative to demanding such sweeping change is a silence which implies complicity. That, on today of all days, is too high a price to pay.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.