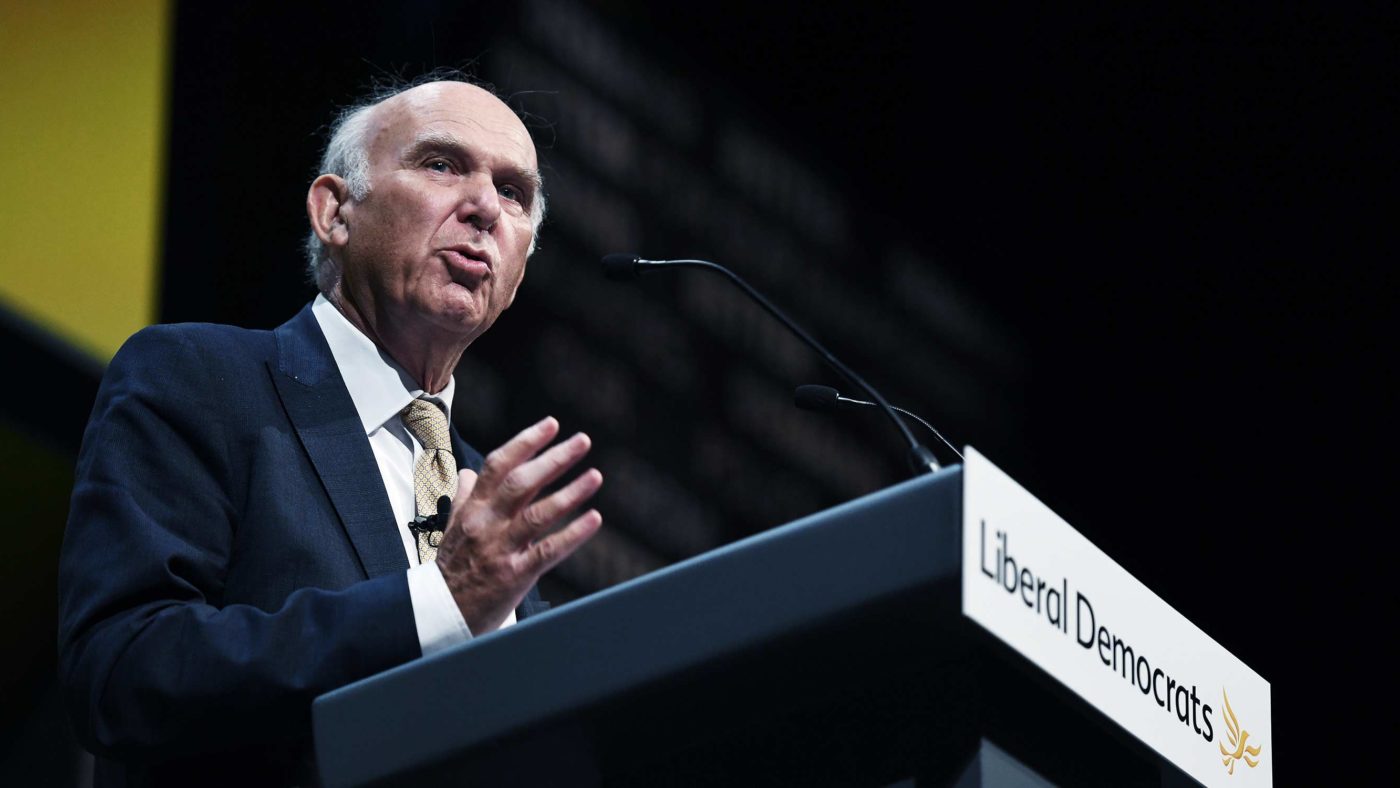

Earlier this week the former leader of the Liberal Democrats, Vince Cable, wrote a decidedly illiberal opinion piece for The Independent, on relations between the West and China. His call for co-operation on trade and climate change is one thing, but what dismayed both Lib Dem MPs and human rights activists is Cable’s contention that the West should desist from “alleging” genocide against Xinjiang’s Uyghurs. That argument is as erroneous as it is worrying.

Take his claim that the events in Xinjiang cannot be deemed genocidal because there is no “evidence of mass murders” and his dismissal of what he calls the “much broader legal construct… [which] looks a little like trying to devise a crime that will fit the accused”, If we assume he’s referring to the 1948 Genocide Convention, Article II states that any of the following acts should be deemed to be genocide: a) killing members of the group; b) causing serious bodily or mental harm; c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; d) imposing measures intended to prevent births and e) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Even if we accept that there has not been mass murder in Xinjiang, there is ample evidence of the remaining four clauses being carried out on a shocking scale. The treatment meted out to the Uyghurs includes sleep deprivation, beatings and other forms of torture, mass incarceration in ‘re-education’ camps, the forcible removal of children to state orphanages and, perhaps most shockingly of all, mass forced sterilisation programmes.

This has all been carried out with frightening efficiency; Adrian Zenz, an expert on Chinese repression in Xinjiang, has shown that the natural population growth rates in the region fell by 84% between 2015 and 2018. By way of rebuttal to the numerous survivors’ testimonies which corroborate this information, Cable points to a non-peer reviewed, anonymously written document, which has already been widely debunked.

Nor is there any doubt about the “intent to destroy” mentioned in the Convention. Whilst the CCP, for obvious reasons, has not admitted to any such intent publicly, how else can we interpret a Chinese official’s order to “break their lineage, break their roots, break their connections, and break their origins”?

Bafflingly, Cable claims the CCP’s real intent is not the destruction of the Uyghurs’ culture, but to clamp down on terrorist activity, in much the same way Western countries did in the aftermath of 9/11. It’s an extraordinarily naive view, especially given the way that authoritarian states, not least Russia, have co-opted the language of the War on Terror to legitimse their own oppressive domestic policies. It’s true that there have been serious outbreaks of violence in Xinjiang, particularly since the Baren uprising in 1990, but each outbreak has had its own local specificities and they have been predominantly the work of separatist groups, not Islamist extremists. The CCP knows that the international community is more likely to turn a blind eye to its human rights abuses if it re-packages them as ‘counter-terrorism’. It’s particularly concerning to see someone of Cable’s standing taking these claims at face value.

Another dubious argument he makes is that using the word ‘genocide’ wrongly puts the CCP’s activities in Xinjiang “on the same moral plain as the Holocaust”. We can only presume he’s missed the fact that numerous members of the Jewish community have made precisely this comparison, including Holocaust survivors Ruth Barnett and Dorit Oliver Wolff. Indeed, Marie van der Zyl, the President of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, wrote to the Prime Minister to warn him of the “similarities between what is reported to be happening in China and what happened in Nazi Germany”.

Leaving aside his quibbling about the definition of genocide, there’s a more fundamental flaw in Cable’s position. Either he is convinced that the CCP is not carrying out a genocide, and is morally comfortable with what he admits are human rights abuses, or he is uncomfortable with them but has decided that engagement with China is in our interests nonetheless.

If the former, he need only look at the mountains of evidence to the contrary from survivors and campaigners working on behalf of the Uyghurs. If the latter, he should re-read his own words of 2018, when he said that

‘The UK has a strong, proud history of democracy and human rights, but our reputation on the world stage is in danger of being eroded by this Conservative government’s desire to woo world leaders like Trump and Erdoğan.’

It would be fascinating to ask him why he finds these leaders so morally repugnant, but thinks we should be more accommodating to Xi Jinping.

Fundamentally, Cable’s approach to the Chinese state is wrong. As Iain Duncan Smith rightly stated in a recent commons debate, closer engagement with China on issues such as climate change should not mean inaction on human rights. To ignore events in Xinjiang on the basis that China is a powerful and competent nation state is a serious abrogation of duty to oppressed peoples and an affront to true liberal values.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.