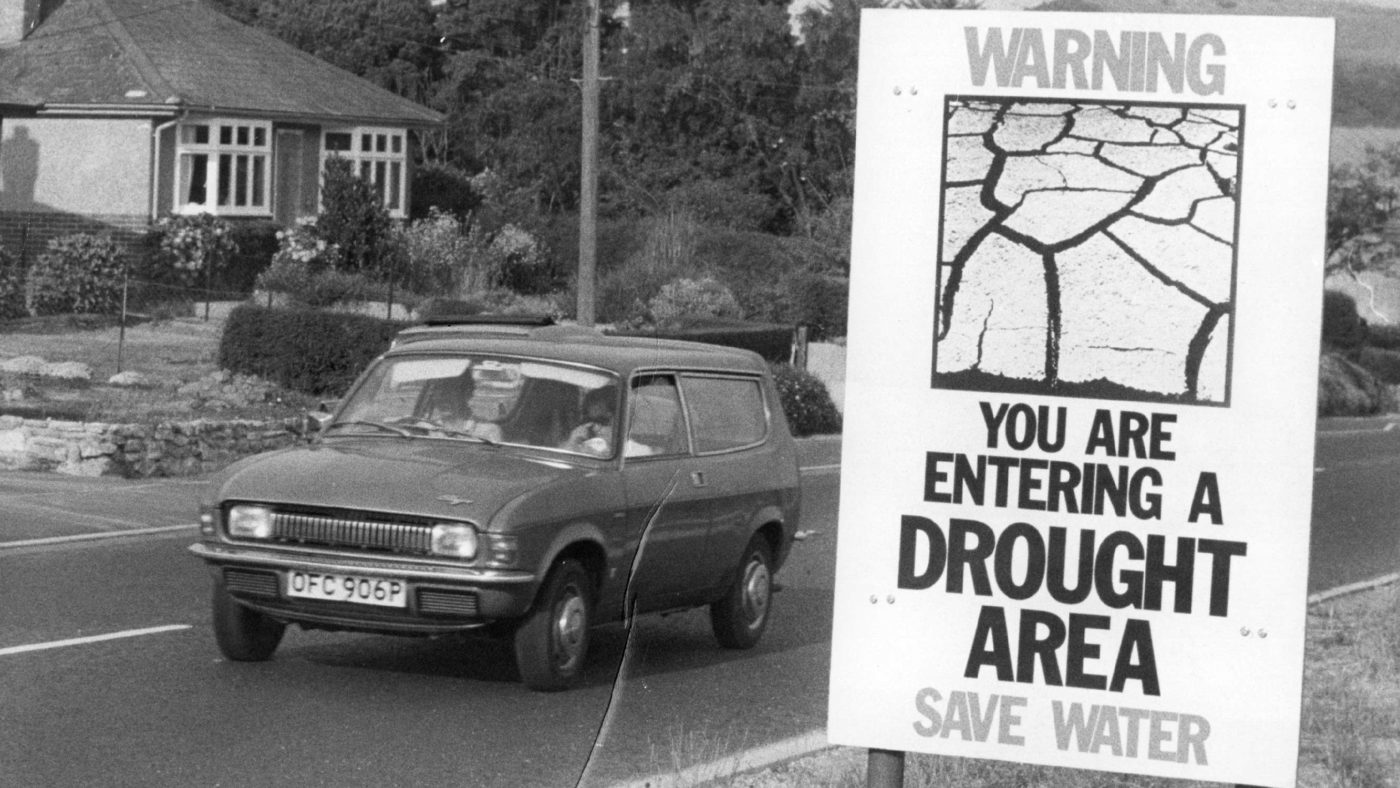

July 2022 was the driest July in England since 1935. Combined with record breaking temperatures, we are hearing talk of a drought comparable to the great drought of 1976, with fears of disruptions to public water supply and poor crop yields, especially for fruit and vegetables. But not all droughts are the same and not all farmers are affected by the same type of drought.

To a meteorologist, drought is usually defined as a period of significantly below-average rainfall. However, low rainfall even over a whole season does not necessarily mean the water supply will run low, or that industry or agriculture will suffer, since there could be lots of water already stored in reservoirs and groundwater.

Of course, such reserves are little help for grassland, cereals and other crops that are entirely rain-fed and are badly impacted when we get a dry spring and summer. The past 12 months have been particularly dry over much of the UK and since May 2021, only October and February have recorded above-average rainfall.

Things are even worse if combined with the high temperatures and plentiful sunshine we have seen this year, which increases evaporation and depletes soils of the water required for plant growth – a so-called ‘agricultural drought’.

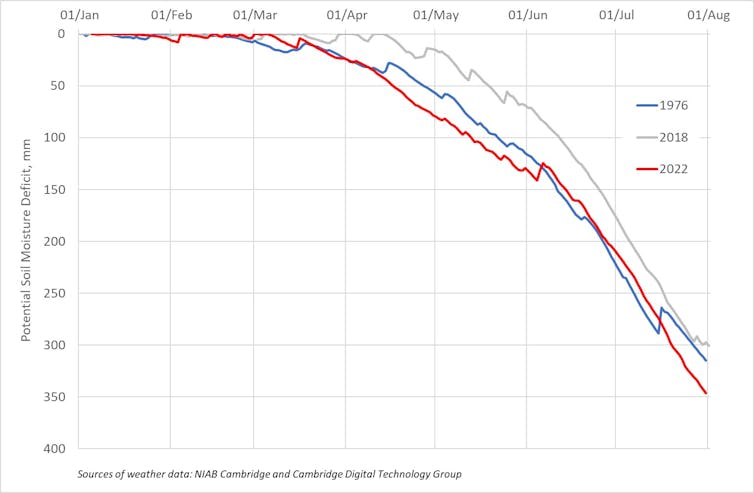

We have evaluated the combined impact of the low rainfall and hot, sunny weather using potential soil moisture deficit (PSMD), which is a cumulative measure (in millimetres) of the balance between rainfall input to the soil and potential losses through evaporation and plant transpiration.

When evaporation exceeds rainfall, the soils become drier and the PSMD increases. When it rains, it reduces. Usually, the PSMD starts to increase from late March or early April, peaking in August or September when the soils are at their driest. A high PSMD means that rain-fed crops like cereals and grass, as well as our gardens, will suffer.

Using data from weather stations in Cambridge, we estimate the PSMD in 2022 has (so far) behaved very similarly to 1976. The deficit started to increase in early March and has continued to grow through to the end of July.

This is in contrast to the last drought in 2018, when the spring was wetter and the soil drying was delayed. PSMD currently stands at about 350mm, which is around 50% higher than the average peak between 1981 and 2010. So for farmers that rely solely on rainfall, 2022 looks like it could be as severe an agricultural drought as 1976.

.

Potential Soil Moisture Deficit (PSMD) in Cambridge, UK, in 1976, 2018 and 2022.

NIAB Cambridge and Cambridge Digital Technology Group, Author provided

Irrigated farming might be restricted

Most grassland and ‘broadacre’ crops like cereals and oilseeds are grown in the UK without irrigation. It is not that they don’t need the water, but that it is financially unattractive to invest in irrigation equipment.

However, to ensure yield and particularly crop quality, much of the UK’s potato, vegetable and fruit crops are given extra water from irrigation during dry periods. Dry soil also means that demand for water for irrigated crops will be higher, competing with reduced available water resources for other sectors.

To the water resources manager, a ‘hydrological drought’ is when the water available in rivers, reservoirs and groundwater is insufficient to meet demand – including demand to maintain a healthy aquatic ecosystem.

.

.Spud soaking: potato is the UK’s main irrigated crop. Giovanni Arrè, Author provided

Potatoes account for more than half of the UK’s irrigated area and volume of irrigation water used. In a dry year, we estimate that a hectare of potatoes (just over half a football pitch) needs more than 2 million litres of irrigation water to maintain yield and quality. That is more than 40 litres for every kg of potatoes.

As UK irrigated agriculture and horticulture needs lots of water but is regarded as a non-essential user, irrigated farmers are at risk of mandatory restrictions during a drought, with potentially severe financial implications.

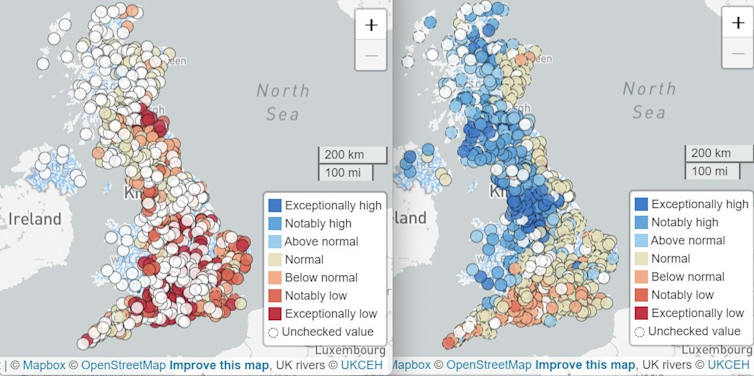

Here we see a difference between 1976 – which followed a very dry 1975 – and 2022. The Met Office described rainfall in 2021 as ‘unremarkable‘. This, together with better water metering and investment in infrastructure to move water from areas of availability to need, means water resources are in a better condition now than they were in 1976.

The maps below show the status of river flows across the country in February 1976 and February 2022. Pinks to reds indicate river flows that were below normal (pink) to exceptionally low (crimson) for the time of year.

So while this year’s dry and hot weather has been similar to 1976 with similar effects on our gardens and farming, last winter finished with water resources that were mostly around normal for the time of year. This means we don’t expect widespread mandatory restrictions on irrigated farms, although some restrictions may be imposed to protect supplies in certain catchments.

.

River flow was much lower in the spring before the 1976 flood (left) compared to 2022. Data: UK Water Resources Portal, Author provided

However, despite the water resources situation not being as severe in 2022 as it was in 1976, demand across all uses needs to be managed to prevent a severe hydrological drought this year. It is also prudent to manage our water resources carefully in the summer of 2022, not only to avoid restrictions this year but also to reduce the risk of more severe restrictions next year if the UK follows this dry summer with a dry winter.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.