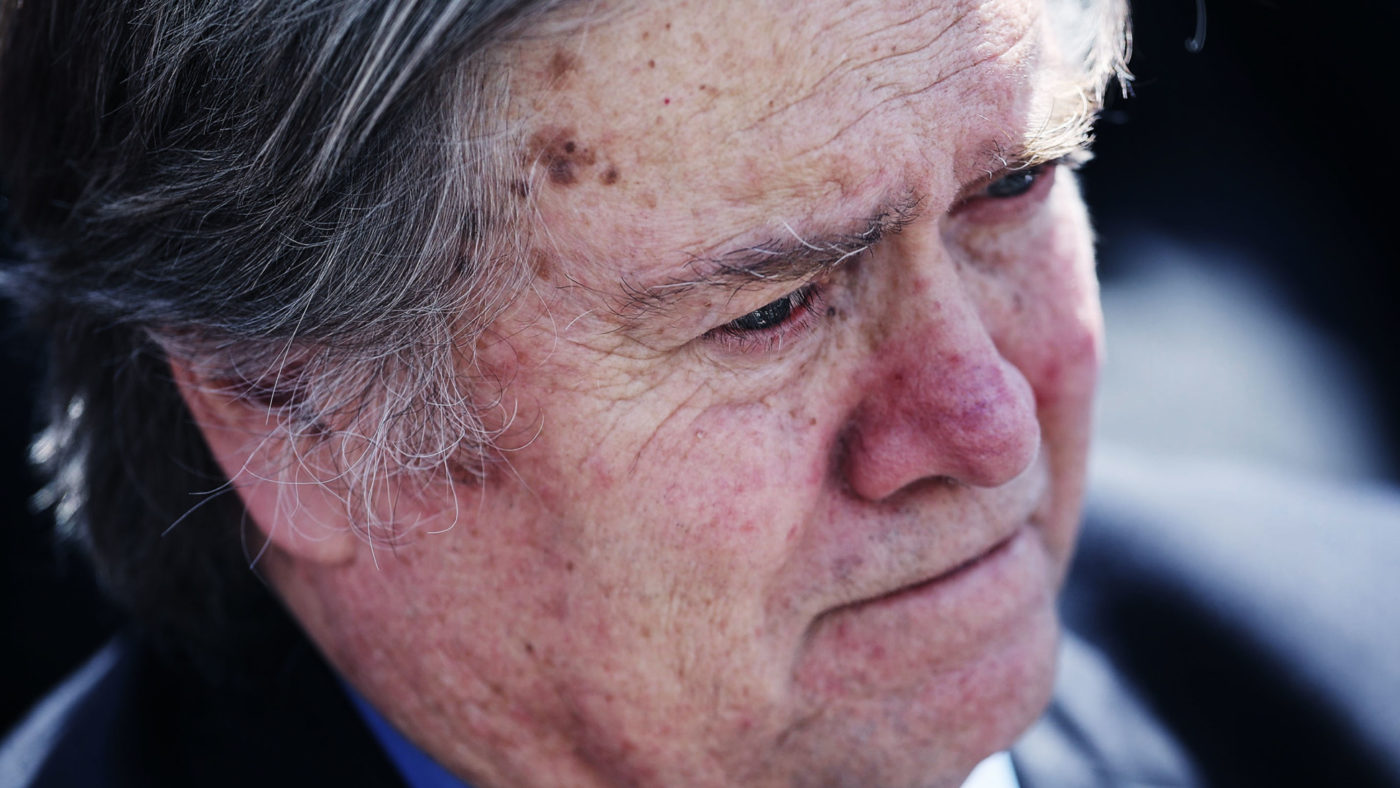

Steve Bannon was the grand wizard of Donald Trump’s media game, the designer of the alliance of the alt-right and the anti-president.

This alignment usurped the Republican nomination process, then undermined the Democrats’ vote in the post-industrial states of the North-East and carried Trump to the White House. But Trumpism, as the strategy was called, failed to turn its desires into policies, and its policies into laws.

The “administrative state” is still administrating. The “swamp” is undrained. The insurgents have been repelled from the walls of Washington, DC. Hours after clearing his desk, Bannon admitted as much. “The Trump presidency that we fought for, and won, is over,” he told the “Never Trump” Weekly Standard last Friday.

Now that his game at the White House is over, Bannon, more petulant child than Sun Tzu or Lenin, is taking his ball with him. “We still have a huge movement,” he said, “and we will make something of this Trump presidency. But that presidency is over. It’ll be something else.”

Unfortunately for the United States and the rest of the world, Bannon may well be right on both counts. It was Bannon who marshalled the rabble of Breitbart into Trump’s rallies, and who turned the Republican Party’s base against its institutions and leadership. It was Bannon who claimed that the Trump candidacy had a coherent ideology, and a strategy for turning it into policies and laws. In other words, it was Bannon who believed, and who did his best to convince everyone else to believe, that there was such a thing as “Trumpism”.

Belief in the existence of this political unicorn ran high in the interlude between Trump’s victory and his accession, and in the early weeks of his presidency. Trumpism even acquired an intellectual forum, a journal called American Affairs. Last week, its founder, Boston hedge fund manager Julius Krein, disavowed his support for Trump.

Krein had hoped that Trump might move America past “partisan stalemates”, and that Trump’s willingness to “do deals” might be a practical way of preparing America’s “weak economy and social fabric”.

“It is now clear that we were deluding ourselves,” Krein wrote in the New York Times. Trump’s administration has “committed too many unforced errors”, and failed to advance an effective legislative programme. Trump has degraded the presidency, notably by pandering to racists. “Far from making the transformative ‘deals’ he promised voters, his only talent appears to be creating grotesque media frenzies.”

If Trumpism existed at all, that is all it was: a pastiche of politics. In the early days of Trump’s presidency, when the executive orders were flying and the swamp-draining was meant to be starting, a photographer visited Steve Bannon in his office in the White House. One of the photographs happened to include the to-do list on a whiteboard behind Bannon’s head. Bannon had already crossed out a couple of items.

Yet none of Trump’s missions had been accomplished. The Wall is unbuilt. Obamacare has yet to be replaced. But Bannon had ticked these items off his list anyway, because Trump’s executive orders amounted to gestures in the right direction. Trump and his courtiers have proven unable to translate his promises into legislation — despite the Republican lock on both House and Senate. For this reason as much as the incompetence of Trump’s administration, Bannon’s influence was waning long before he left the White House.

Trumpism was nothing more than gestures — a media act, not legislative action. And Trump himself is a personality cult, not a political programme. This farce reflects the collapse of American politics into a subsidiary of the entertainment business. As in WWE wrestling, the characters are actors, the moves are rehearsed, and the enmity is fake. The crowd know it’s just a show, but call for blood anyway. Every now and then, someone actually gets hurt.

It is bad enough that much of the Republican Party’s base has succumbed to this circus of resentment. No doubt Bannon, its ringmaster, will devise new entertainments; he is already rumoured to be planning a new TV station. It is worse that almost the entire body of the Republican Party’s elected representatives have played along to the Bannon & Trump show in the hope of being granted walk-on roles.

Trump, Julius Krein said last week, is effectively “a third-party president without a party”. The other way of looking at this situation is that the Republicans are a party with majorities in both House, and that Trump’s nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court has further strengthened their position.

America’s economic and social problems have not developed overnight. In the last five elections, the electorate’s consistently rewarded candidates who promise to fix those problems. Before the 9/11 attacks turned George W. Bush into a war president, Bush won the 2000 election on a platform of “compassionate conservatism”. Similarly, Barack Obama won in 2008 with “nation-building at home”, and Donald Trump in 2016 with the promise to Make America Great Again, by all means necessary.

The Trump presidency is a vacuum, in morals as in policy. The Republicans must capitalise on this. Domestically, they should use their legislative advantage to advance the policies that the electorate has consistently shown it wants — policies leading to good jobs, productive schools, affordable healthcare, working infrastructure, and the mix of social mobility and social stability that Americans have come to consider their birthright. On foreign policy, where the president enjoys more leeway and has shown no ability to use it constructively, Republicans must make explicit their disapproval.

The Republican leadership tied it to an antagonistic presidential candidate because it feared the anger of the party’s base, and because it wanted power at all costs. Whatever happens next, it cannot disassociate itself from Trump.

If there is no such thing as Trumpism, then the Republicans can at least repair some of the damage to their reputation, to conservatism, and to American democracy, by presenting coherent legislative alternatives to Trump’s rule by Twitter.