Unsurprisingly, the Conservative leadership election has so far been dominated by Brexit. But Conservative Party members, and the country at large, will want to know more about prospective party leaders’ – and Prime Ministers’ – stances on a wide range of areas.

One such issue is the environment, which by any indication has rocketed up the pecking order of what is occupying voters’ minds. In spite of a seemingly never-ending string of bans on all that is plastic from the Government, the hunch that a typical Tory member still lags behind the general public when it comes to environmental conscientiousness persists.

Yet, there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that this is an outdated stereotype. Survey data from YouGov shows that fewer than one in five Conservative Party members want to see less of an emphasis on environment and climate change. Polling commissioned by think tank Bright Blue last year found that Conservative voters are in lock step with the rest of the population when it comes to wanting cleaner air.

What about the attitudes of the electorate more generally? The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) recently published the latest round of results of its ‘Public Attitude Tracker’ – a quarterly survey which asks questions relating to energy policy. It gives a good insight into the mood of the British population, and, from the perspective of a possible leadership candidate, a handy guide to shaping their own thoughts on what policies they may (or may not) want to champion if they’re to be seen to be in touch with ordinary people, and thus capable of winning a general election.

And any environmental agenda should start with the biggest environmental issue: climate change. Concern about this problem should not be underestimated.

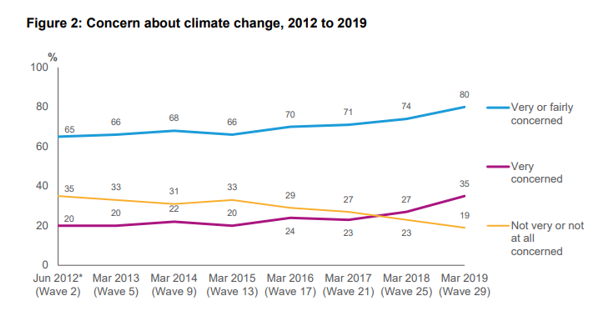

Eighty per cent of the British public say that they are concerned about climate change, nearly half of whom are ‘very’ concerned. In contrast, fewer than one in five are either not very concerned or not at all concerned – nearly half the number compared to when BEIS first started asking in June 2012.

You might think these numbers are inflated by massed ranks of young activists, but dig into the data and you soon find that attitudes don’t change much across age bands – with those aged 55-64 years old just as concerned as those aged 16-24 years old.

While the US president may have snuck into high office in his country pushing a climate-sceptic agenda, his would-be British counterpart may fare differently if he or she were to adopt such a platform over here.

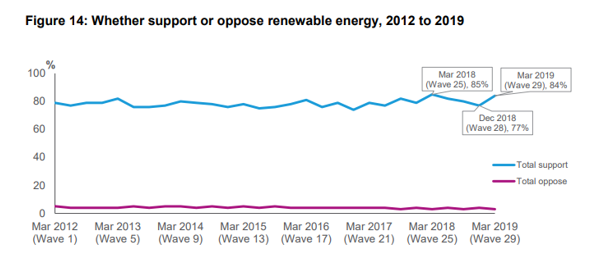

Being concerned about climate change is one thing, actually dealing with it is another. Much will depend on how successfully the UK manages to decarbonise its energy supply. Certainly, fossil fuelled energy generation will need to be replaced by a mix of alternatives, with renewables taking a far greater share of the total. Here, the British public swing overwhelmingly in one direction – with net support for renewables standing at 84 per cent in favour, to the rounding error of just three per cent in opposition.

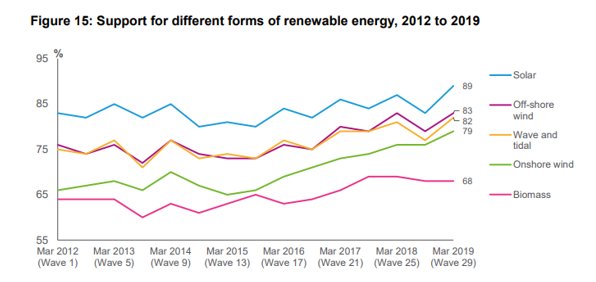

Of course, there are lots of different ways to generate renewable energy, and opinions differ unsurprisingly on each form. Solar, for instance, continues to be the method of preference, with nearly nine in ten people backing it. Offshore wind comes in second, attracting the support of 83 per cent.

What might raise most eyebrows, however, is the sheer popularity of onshore wind – which, perhaps contrary to the fears of many a Conservative MP, almost four in five people are happy to see more of. In light of such evidence, might we see any candidate brave enough to give their backing to the development of further onshore wind turbines? Separate polling should offer more reassurance, with 60 per cent of Conservatives voters supporting the policy of doing so.

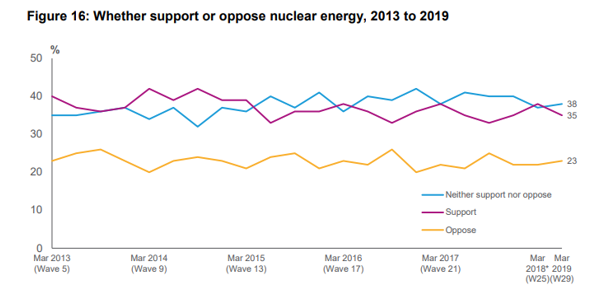

For when the wind isn’t blowing or the sun isn’t shining, the UK currently relies largely on a combination of natural gas, coal and nuclear power. If the former two are to be phased out, nuclear power will be left doing a lot of the heavy lifting to keep the lights on. On this energy source opinion is more fractured, but support for it nonetheless stands significantly higher than opposition to it.

Over a third – 35 per cent – of the public are pro-nuclear, versus 23 per cent who are anti. If we (admittedly rather arbitrarily) split the ‘neither support nor oppose’ responses down the middle and distribute the results evenly, an overall majority of the British public would be in favour of this low-carbon source of energy. While nuclear power certainly has drawbacks of its own – namely, high cost per megawatt hour – leadership candidates would be wrong to think of it as the taboo some have tried to badge it as.

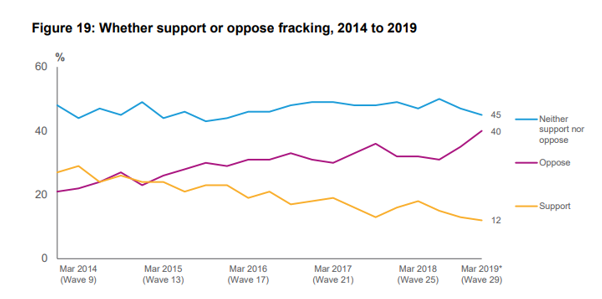

The truly unpopular source of energy, from the BEIS survey at least, is fracking. Getting energy from shale gas is one of the most frowned upon sources in the UK, with more than three people in opposition to it for every one person in favour. Indeed, for the last four years now, more people have explicitly opposed fracking than have supported it.

Among those who claim to know either a little or a lot about fracking (who one might reasonably assume will be the most politically engaged), opposition swells to an overall majority – 56 per cent – while support increases only marginally.

A lot a Conservatives have in the past sung the praises of fracking as a means of cheap energy which could help as a stepping stone to a less carbon intensive grid. While they doubtlessly knew that it would irate any garden variety lefty, they probably assumed they might’ve had support from the right. The figures above, however, would indicate that backing fracking looks like a risky move.

An obvious caveat to all of the above, and with the example of fracking in particular, is that stated preferences on surveys are patently not revealed preferences in reality. Or in other words, what a voter says they care about does not always match with how they end up behaving in the privacy of the ballot box.

If the UK were to press ahead with shale gas extraction which managed to deliver cheaper energy, fracking could be more popular – in America, it has cut the cost of gas and provided new jobs. On renewables, their overwhelming popularity in polls does translate to a similar proportion of households who are signed up to ‘green’ tariffs. At the same time, renewables’ favourability is often contingent on size and location (think NIMBYism for wind turbines). And, if the recent Australian election is anything to go by, arguments about costing consumers, rather than costing the earth, still appear to hold significant electoral sway.

But this is not to say that the Conservatives should ignore the environment – such an approach would be disastrous. But they do should try to balance reducing greenhouses gases with practical matters like aesthetics and cost. They need to prioritise the environment, but in a way that fits with wider conservative attitudes.

When the Conservative Party finally whittles down the clutch of MPs who are vying to become Prime Minister to just two candidates, it will be down to perhaps 120,000 or so grassroots members to have the final say.

On some issues, these are two very different constituencies. Comparing the Tory membership with the wider public, those gaps in opinion can become seismic. But on the environment, there is perhaps a surprising amount of overlap. Leadership candidates and the country’s privileged ‘selectorate’ might find it judicious to keep the above charts in mind over the coming weeks – and set out how to deliver what the public want in a cost effective and practical way.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.