After the Brexit vote, the concerns of low-income voters and struggling communities took centre stage in British politics. Both parties made concerted pitches to win them over, in the shape of Theresa May’s focus on the “just about managing” and Jeremy Corbyn’s anti-austerity platform.

And yet in the 2017 election, both parties failed to make a dramatic break-through among low-income voters. As the Conservative Party examines how it can regain a majority, our new research shows that it should begin by looking at its offer to blue-collar workers and people who are struggling to get by.

Analysis of the result by Matthew Goodwin and Oliver Heath for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation paints a detailed picture of what motivated voters’ decisions. Drawing on data from the British Election Study, it drills down into their backgrounds, attitudes and values.

In the wake of the election, the fault lines of age and education received a lot of attention. But our data shows why low-income voters mattered too.

Both parties had some success among these voters: each increased their support by about eight percentage points. But while the Conservative message on Brexit was attractive to many, Labour’s message on living standards and the economy attracted them much more. So the Conservatives hoovered up votes from UKIP – but the “Brexit effect” alone was not sufficient to for them win a majority.

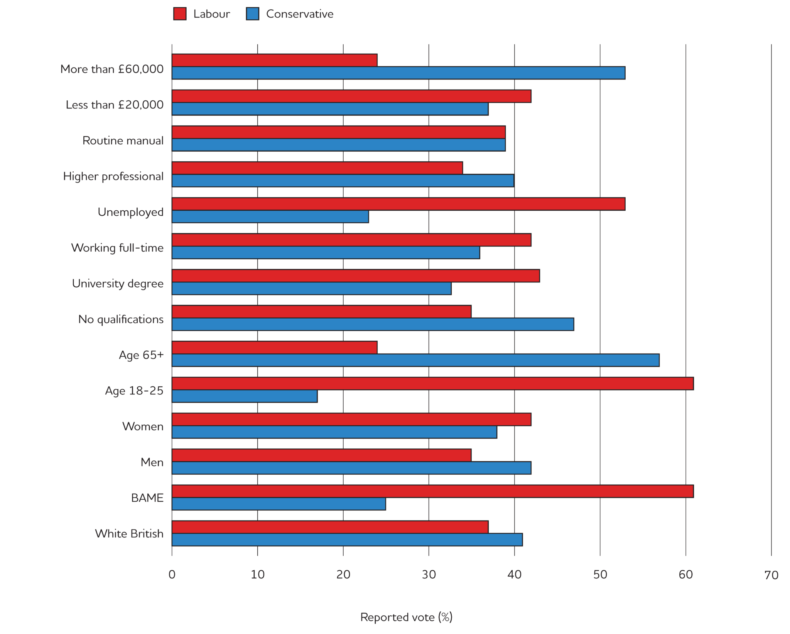

In total, 37 per cent of low-income earners (those with incomes of less than £20,000) voted for the Conservatives, compared to 42 per cent for Labour. By contrast, people with high incomes (over £60,000) remained much more likely to vote Conservative than Labour: 53 per cent compared to 24 per cent.

Despite May’s focus on the “just about managing”, people who thought their household finances had gotten worse over the past year went for Labour by a considerable margin: 48 per cent to 27 per cent. In contrast, those who thought that their financial situation had improved went for the Tories by 52 per cent to 29 per cent. The problem was that there were hardly any of them: just 13 per cent of the electorate. With inflation rising, wages stagnant and low rates of growth, this is an ominous finding for the party.

This not only countered, but often outweighed, the Brexit effect. In the estimated 140 Labour seats in England that voted for Brexit, the average Conservative vote increased by 8.3 per cent, compared to an average of 4.6 per cent across England as a whole. But despite substantial advances in struggling, pro-Brexit, Labour-held areas such as Heywood and Middleton, Wentworth and Dearne, Stoke-on-Trent North and Don Valley, the Conservatives failed to win. In fact, Labour captured more than a dozen Tory seats that are estimated to have voted for Brexit.

Labour is currently enjoying its conference in Brighton, buoyed by its stronger than expected performance at the election. But the good news for the Conservatives is there an opportunity for them to bounce back.

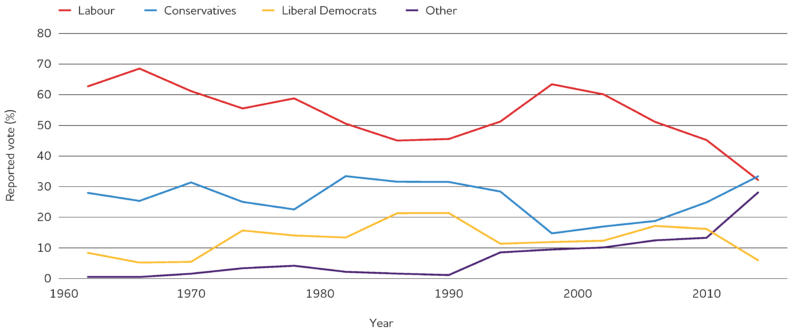

Labour’s relative electoral success was driven by young people and the highly educated. Among low-income voters – once its natural home – its lead is weaker. This leaves space for the Conservatives to catch up and even overtake Labour next time. Indeed, as this chart of the working-class vote shows, workers’ support is now up for grabs: the Tories are neck-and-neck among manual workers with Labour, on 39 per cent each, and actually lead among voters with no formal qualifications (47 per cent to 35 per cent).

At the next election, low-income voters will be the key battleground. And if the Tories can make an attractive pitch that convinces such people they are on their side, they will be in with a shout.

But that pitch must go beyond delivering Brexit. It must include bold action on the domestic agenda: addressing the chronic shortage of housing; ensuring there’s more competition in key markets to reduce the crippling cost of living; supporting low-skilled workers with retraining so they’re not left behind by rapid economic change; and boosting pay and productivity in places where this has been lagging.

Fractures are appearing in the British electoral landscape and Brexit showed the country wanted change. As Robert Colvile noted on CapX earlier this week, attracting younger voters is vital to future Conservative success. But without the strong backing of those who feel their living standards and prospects are getting worse, neither party can gain what eluded them in June – a parliamentary majority.