How serious is Venezuela’s crisis? Bad enough that, in 2016, Venezuelans became the top US asylum-seekers, having surpassed Guatemalans, Salvadorans and Mexicans. Venezuelan asylum claims increased by 150 per cent from 2015 to 2016. ![]()

Though Venezuela does not publicly circulate emigration information, estimates suggest that between 700,000 and two million Venezuelans have emigrated since 1999

In 2015, 197,000 Venezuelans lived in the US, according to a recent United Nations study. Other major host countries were Spain (151,594 Venezuelan residents), Italy (48,970), Colombia (46,614) and Portugal (23,404).

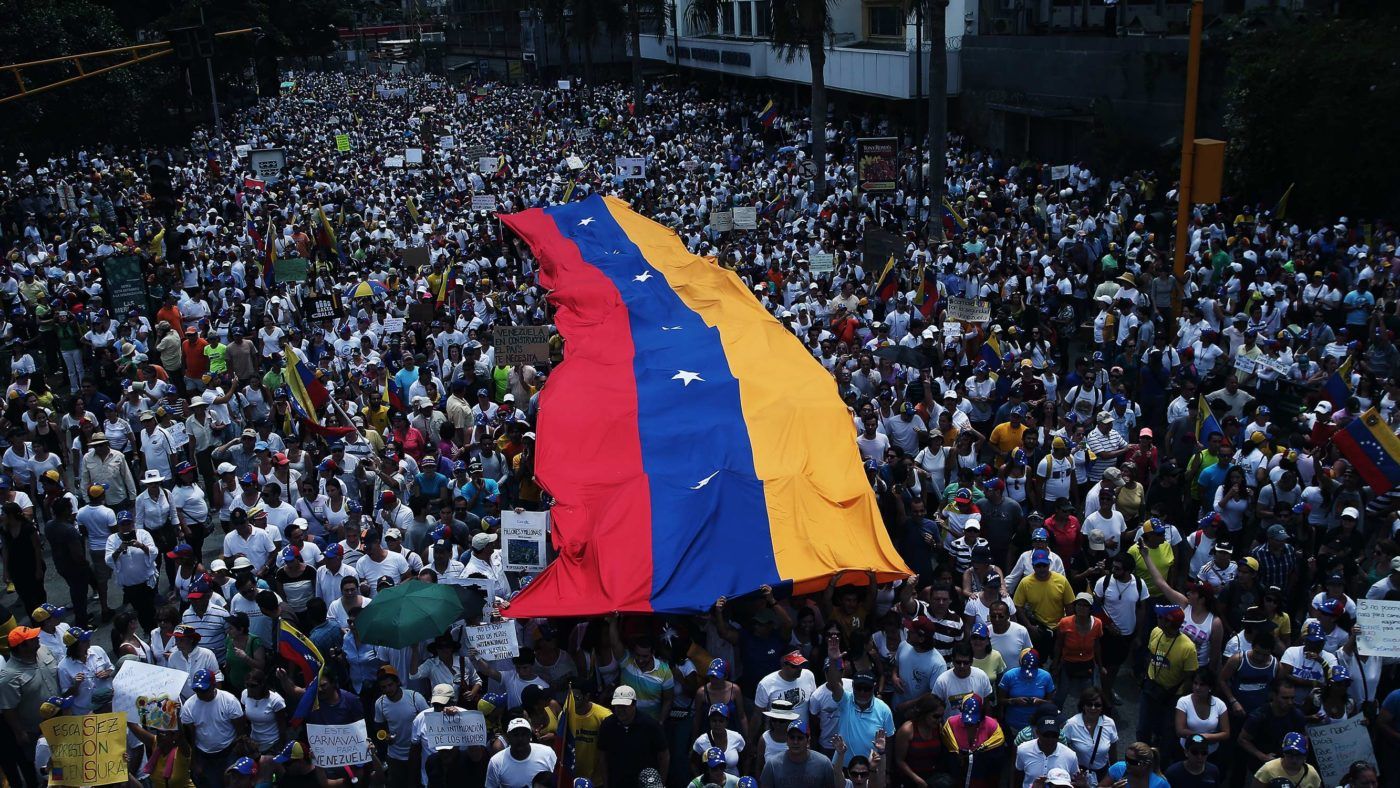

Venezuela is in the midst of a severe national crisis, with millions of citizens impoverished by the drop in international oil prices, a reduction in imports, scarcity of food and medicine and hyperinflation.

High crime, polarisation and corruption have deepened this troubling scenario.

The result is a society that’s paralysed, disillusioned and desperate. These circumstances have driven thousands of precariously employed, hungry and frustrated Venezuelans to emigrate. Whether by land or by sea, they are fleeing – many to neighbouring countries such as Colombia and Brazil – seeking a better life.

State repression is also, without doubt, a cause of the exodus from Venezuela. According to a 2016 report from the Venezuelan Penal Forum, the country saw 2,732 political arrests in 2016. (In comparison, Cuba had about 97 political prisoners in 2016 and the US had a similar number.)

The report describes three types of political prisoners in Venezuela: those who present a political threat to the government; those who do not themselves present a threat but are arrested to send a message to their followers and other opposition members; and those who do not constitute a political threat of any sort but who are detained to support the regime’s political narrative.

In Venezuela today, state terrorism is used to stoke fear among citizens. Prosecuting dissidence has become official policy.

Venezuela’s current flow of emigrants and activists belies the country’s historic immigration pattern. Over the past seven decades, Venezuela has welcomed numerous waves of foreigners, most of them hoping to take part in the nation’s 20th century oil bonanza.

From 1948 to 1958, some 400,000 immigrants arrived from southern Europe. These Spanish, Portuguese and Italian migrants filled demand for labour in Venezuela’s agriculture, construction and industrial sectors. By 1970, another 298,000 intellectuals, professionals and other high-skilled workers had come from elsewhere in South America, fleeing military dictatorships.

In the 1980s, 800,000 immigrants flocked to Venezuela from neighbouring countries – particularly from Colombia, then suffering the worst of its armed conflict. These new arrivals, who took jobs in the service sector, agriculture and industry, are now fleeing impoverished Venezuela to return home.

Sometimes, from here, it can seem as though the entire population – fed up with shortages of medicine and food, with crime and with the political trajectory of the nation – wants to leave.

This graph shows Venezuelan asylum claims in the US over the past 13 years. The ups and downs correspond to particular sociopolitical junctures in the US and Venezuela alike.

The current wave of out-migration can be traced back to 1998, when the election of president Hugo Chávez sent the wealthy packing. Bankers, captains of industry and merchant class, escaping the febrile environment that lead to an oil strike in 2002 and attempted coup d’etat in 2003, left for the US and Spain.

A second wave of émigrés was compelled by Chávez’s Bolivarian government to abandon the domestic oil and gas industry. Between 2003 and 2008, many highly skilled industry professionals left Venezuela, lured away by multinational companies such as ExxonMobil and Chevron, then in legal proceedings against the Venezuelan state.

Between 2008 and 2012, Venezuelans with a second passport, a university degree and family abroad finally pulled up stakes, generally “returning” to the homelands of their parents and grandparents. The current uptick in asylum requests begins in 2009, reflecting the reduction in oil revenues in Venezuela and, perhaps, also the beginning of Barack Obama’s presidency after he promised not to prioritise the deportation of undocumented immigrants who had committed no crime.

But it really takes off after president Nicolás Maduro assumed office in 2013 as successor to Chávez. During the social upheaval that followed in 2014 and 2015, three young people were killed in protests and dozens arrested. This was the beginning of the crisis that drove Venezuela to top the list of countries of origin for US asylum-seekers.

The cancellation of a proposed referendum to recall president Maduro surely compelled even more people to make this risky choice.

Still, immigration is not asylum. Every asylum claim must have a political basis. No other motive for fleeing – be it hunger, sickness, joblessness, or poverty – counts.

To qualify for asylum in the US, the applicant must demonstrate “credible fear” of returning to their home country – fear of being persecuted by the government based on one’s political or religious beliefs, nationality, race or membership of a particular social group.

The Department of Homeland Security’s 2015 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics reports that from 2006 to 2015, 8,757 Venezuelans sought US asylum. Of those petitions, 6,773 were granted – a 77 per cent affirmation rate.

This high approval rate for Venezuelan asylum seekers, combined with country’s current crisis – in which the right to political dissent and freedom of expression have been criminalised – suggest a high probability that today’s refugees will also be found to have credible fear.

But first they must get into the country. In mid-2015, US border officials in Florida began refusing admission to Venezuelan airline passengers. “Are you afraid to live in Venezuela?” Customs officials would ask, attempting to identify potential asylum seekers entering the country on a tourist or business visa. If they answered yes, they were turned back.

As Jose A. Iglesias wrote months later in Miami’s El Nuevo Herald newspaper, “A majority of Venezuelans, being honest, must answer affirmatively to this question, given the high crime, repression and political violence that imperils the country.”

Interrogations in US Customs continue to be reported on social media. Thus is the state of Venezuelans today: credible fear at the US border, credible fear back home.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.