In her speech at Conservative Party Conference last week, the Prime Minister announced “an end to austerity”. In policy terms, this message has been the main focus of the post-conference talk for the commentariat. With polls suggesting that the public are increasingly weary of constraints on public spending, that rhetoric may make a great deal of political sense. If, however, it means the government moving towards a policy of active complacency over the public finances, then the consequences could be severe.

A report published yesterday by the International Monetary Fund highlights just how precarious our fiscal position is compared to other advanced economies. The latest edition of the Fund’s Fiscal Monitor estimates that the total net worth of the UK’s public sector (i.e. the balance of public assets and liabilities) is close to the bottom of the international league tables, with only Portugal coming lower in a list of 31 countries. A significant contributing factor to this is the UK’s substantial pension commitments, a measure on which we are outdone only by Portugal and Finland as a proportion of GDP.

The Office for Budget Responsibility’s Fiscal Sustainability Report, published in July, set out the scale of the problems the UK faces in managing its public finances over the coming decades (with the key parts handily summed up at the time by the CPS’s Robert Colvile). The OBR did not mince their words when it came to making conclusions from their report: “the main lesson of our analysis is that future governments are likely to have to undertake some additional tightening beyond the fiscal plans in place for the next five years in order to address the fiscal costs of an ageing population and upward pressures on health spending.” The scope for splurging on public services in the upcoming spending review is extremely limited.

As I have highlighted previously on CapX, while the OBR have forecast debt to start falling this year as a percentage of GDP, the fall is only 0.1 percentage points. In fact, they have politely pointed out that on an unrounded basis, the ratio is set to fall by just 0.05 percentage points. While the public finances have exceeded expectations since that forecast was published in March, the government has also committed to substantial extra spending, most notably on the NHS. The OBR also pointed out in March that analysis suggests the probability of a recession in any given five-year period in the UK is roughly one in two, and since we have not had a technical recession for a decade now, the chances of a cyclical downturn before too long are “fairly high”. With debt approaching 90 per cent of GDP, the UK is not in a comfortable position for dealing with another slump.

The other crucial point is that the current forecasts of a neat downward trajectory for public borrowing have substantial spending reductions factored in which have not yet been implemented.

For example, the generosity of the Universal Credit system relative to the old benefits and tax credits was significantly reduced in 2015, but hardly anyone is yet in receipt of the new benefit. Awareness of the hefty impact it will have on the incomes of some households is gradually working its way from think tanks through to journalists and concerned MPs. Today, former prime minister John Major has warned that Universal Credit risks becoming the new poll tax. People in government are desperately hoping that the transitional arrangements they have built in, plus the little bit of extra money given back to the system since Philip Hammond took over at the Treasury, will mean the rollout does not lead to a build up of political pressure which could ultimately force the government to commit substantial extra cash.

This issue also highlights what has been reported as a difference in approach between Theresa May and her Chancellor. Nick Timothy has been of the view for some time now that the public finances are no longer a major concern, and the Prime Minister signalling an “end to austerity” suggests she leans towards this school of thinking. It is a view which will be popular with many departmental cabinet ministers concerned about their budgets and desperate for a good news story.

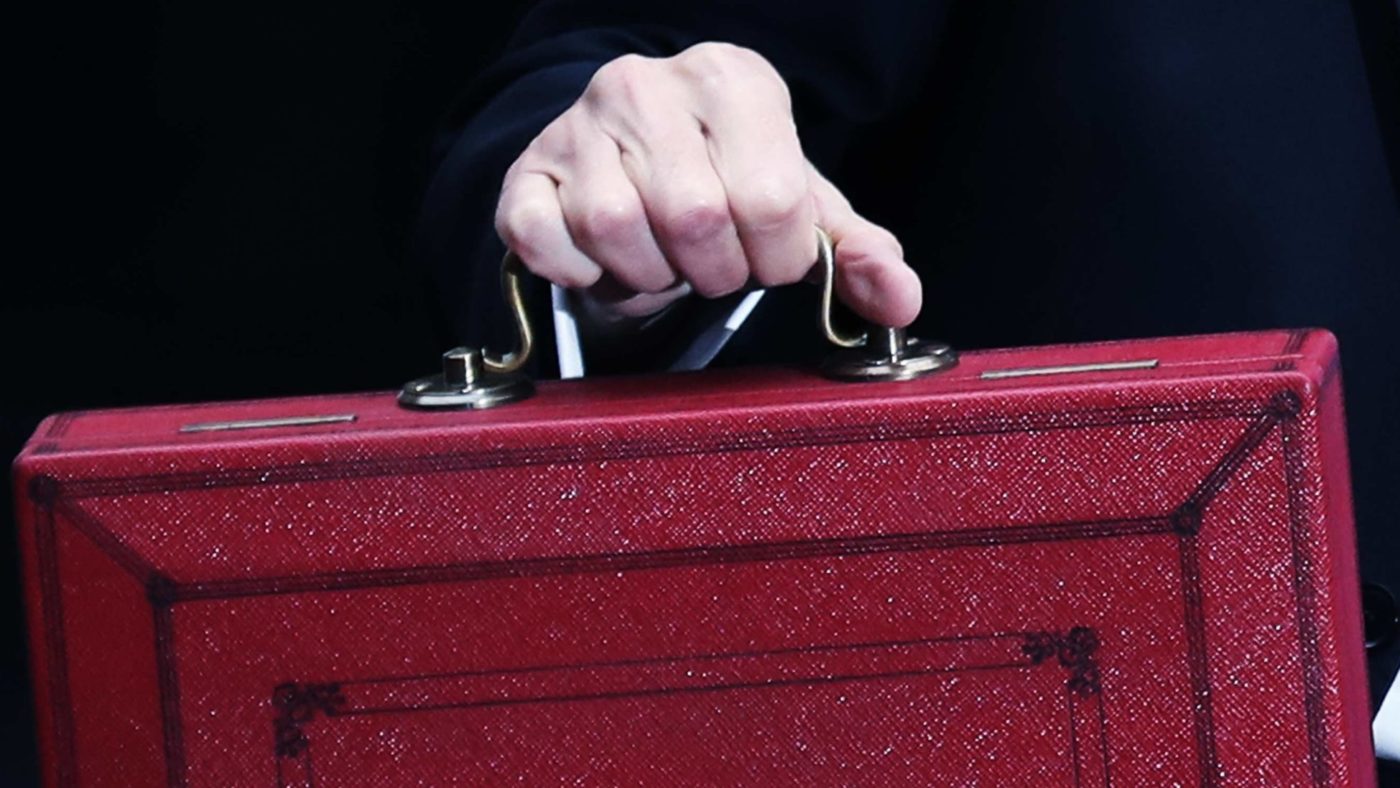

Philip Hammond, on the other hand, is concerned about the UK’s ability to withstand an economic downturn. He is also conscious of the fact that a very large budget increase for the NHS has not yet been funded, and there is little appetite among the Conservative Parliamentary Party for tax rises.

The Centre for Policy Studies is currently working, in conjunction with several MPs, to find areas of public spending which could be trimmed to help pay for the government’s commitments without having to substantially increase taxes or borrowing. There are some very tough choices to be made, but if we pretend now that the finances are fixed and we can afford to substantially loosen the purse strings, we are simply putting off the hard decisions for a later date or a future generation.