As the Chinese think in long time-spans, those who wish to understand them should do likewise. In the late Fifth Century BC, the Marquis Yi died in Wuhan. His grave was magnificently accoutred with bronzes, pottery and ivories; more than enough to kit out today’s museum. There were also cloths and scrolls, which have perished. But they were not the only perishable goods. The Marquis was accompanied by 24 virgins aged around 15. The girls shared coffins. To ensure that they did not struggle, their arms and legs were broken.

One can imagine the scene. In one room, an elegant interior designer would be ensuring that the gilding on the high relief work was just so. He might have had to shut his ears to the screams from next door, as local hoods broke the girls’ bones. To this day, the Chinese retain the capacity to ensure that civilisation and cruelty can closely co-exist.

Traditionally, they have been better at creativity than at exploiting its fruits. The Chinese invented gunpowder, the compass and printing, which they used as toys. Inter alia, the West used them to dominate China.

There was also the Eunuch Admiral. In the early Fifteenth Century he commanded a battle-fleet, including warships that were 400 feet long. Some of them reached Africa, until the then Emperor ordered them all back to home waters. But suppose that Emperor had been a Chinese equivalent of Henry the Navigator. Suppose also that he had sent the Admiral East. It is not so far from China to British Columbia. By the time Columbus arrived in the Caribbean, and long before the earliest English settlements, the Chinese could have established a great new Empire in the Americas. World history would have been entirely different. In recent years, rich Chinese have bought a lot of property in Vancouver. If matters had turned out differently, they would already have owned all of it.

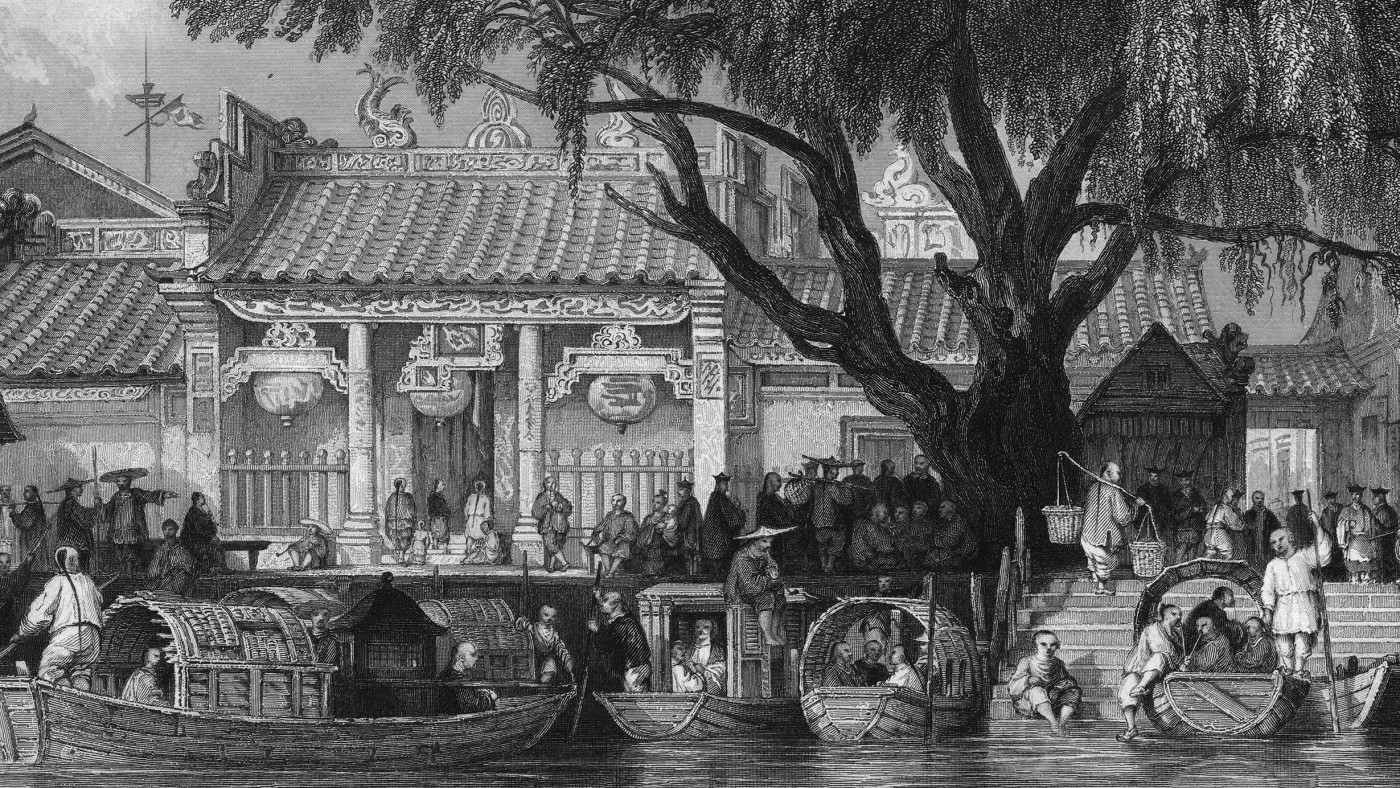

Instead, China turned inwards and was in no technological state to resist Western encroachments and diktats. From the 1840s, the Chinese endured the worst period in their history. They were kicked around by the Americans, the British, the Germans, the Japanese – and by themselves. The Japanese incursions were both brutal and humiliating. Traditionally, the Chinese regarded them as primitive fisher-folk, the offspring of a kidnapped Chinese Princess and a sea-monster, who lived on the fringes of the civilised world. Now they were flaunting their power.

The Chinese are no novices when it comes to feelings of racial superiority. They regard themselves as the greatest of peoples in the greatest of nations. There is an obvious question: how deeply did the decades of maltreatment burn anger into the Chinese soul?

Over the past thirty years, China has made enormous progress. It used to be an axiom that the Chinese had learned how to prosper in every country except China and had mastered every art except politics. The first half is no longer true; the politics may be a work in progress. So how should we arrange our relations with the new China? Caution is surely advisable. We would prefer it if the Chinese enjoyed human rights, the rule of law and democracy, if Tibet were free.

(That said, suppose the Chinese had left Tibet alone, as a tranquil theocracy. Western TV crews and journalists would have smuggled themselves in, to report on Tibet’s backwardness, especially in relation to women, most of whom were denied access to education and spent all their time grinding saffron to dye the monks’ robes.)

There are those who argue that we should protest loudly about human rights during this week’s State Visit. The assumption appears to be that the Chines would be in a mood to submit humbly to such strictures. That is nonsense. If a British Leader were to try to lecture them, he would receive an earful about the Opium Wars, Britain’s record as a colonial oppressor and so on. The Chinese would remember that officially, they are Marxists and Maoists.

So what should we do about human rights in China? There is only one sensible answer: as little as possible. We have to hope that the country continues to progress – and remains one of the engine-rooms of the world economy. The Marxists were not always wrong. There is a connection between economic development and social and political progress. In recent years, there have been signs that the Chinese populace is losing its fear of their government – while the official classes are learning to fear the people. Although we should wish devoutly that this continues, there is nothing that we can do to influence the outcome.

In these times when liberal naivete has far too much influence over debates on foreign policy, the UK Prime Minister David Cameron will have to claim that he said something about human rights. But his message should be a gentle and respectful as possible.