Britain is still coming to terms with the tragic fire at Grenfell Tower – and still casting around for people to blame.

But even as we try to understand how and why these people died, there’s something else we need to grapple with: namely, why were they living in that tower block in the first place?

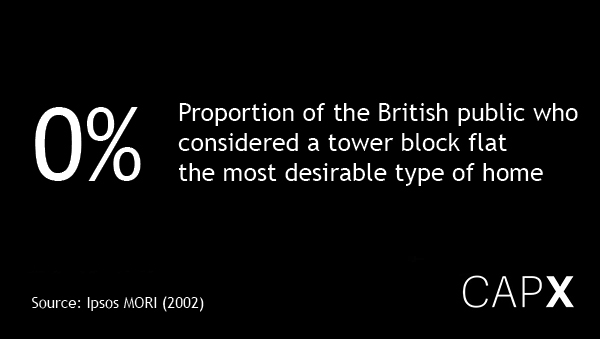

Back in 2013, the think tank Policy Exchange and an organisation called Create Streets published an eye-opening report. The problem with tower blocks, it argued, was that no one wants to live there. In one poll, 89 per cent of people said they wanted to live in a house on a street. Not one person – 0 per cent – said that actually, they’d prefer to be up on the 16th floor. On the Robin Hood Gardens estate in Poplar, 80 per cent of residents said they wanted it pulled down.

The report is so convincing that it’s probably easiest to quote from it at length:

“The empirical evidence is overwhelming. Large multi-storey housing blocks (be they high-rise or medium-rise) are usually disliked and are correlated with bad outcomes for the people forced to live in them, even when socio-economic status is taken into account. They are bad for society and crime levels and a very poor return on investment for those who own them in the long-term. They cost more to build, maintain and fall into disrepair sooner. They are very bad for children and families, yet in particular children in social housing are forced to live in multi-storey homes.

“With very few exceptions… large multi-storey estates are nearly universally shunned by those who can afford to choose. Turning their back, literally, on the rest of the city, many post-war multi-storey housing estates have sadly become physically distinct, self-defining ‘ghettos’. Chris Holmes, the former director of Shelter, concluded that ‘housing poverty is now the most extreme form of social inequality in Britain, with those who experience the greatest inequalities being those living on housing estates.’ Many of these multi-storey estates were badly built and have been poorly maintained. They will need to be rebuilt within the next few decades.”

The evidence cited is compelling. Survey after survey, in country after country, shows that people don’t like high-rise blocks. They want five storeys, maximum. They like private gardens, not communal space. People who actually live in multi-storeys don’t want to have families there. The adults suffer from more stress, mental health difficulties, neurosis and marital discord – and the children suffer from more stress, hyperactivity, hostility and juvenile delinquency. Suicides are higher. So are vandalism and anti-social behaviour. There is less of a sense of community and interaction: “In one study stamped addressed envelopes and charitable donations were placed on hallway floors in college halls of residence. Both were passed on or returned in inverse proportion to building height.”

There are, of course, high-rise buildings that people like living in. But the people who live in them tend to be rich and childless. In the Barbican, for example, the service charge is now roughly £8,000 a year – showing not just the kind of people who can afford to live there, but how expensive these complexes actually are to keep up.

What the report argues, then, isn’t that high-rise estates house people with problems – though they often do. It’s that living on these estates gives ordinary people more problems by their very nature. Moreover, these were never places people chose for themselves. They were something done by the rich to the poor. From the 1950s onwards, the UK demolished 1.5 million homes, largely in streets, and replaced them overwhelmingly with high-rises – an idealistic attempt to build better lives that ended up as a grotesque act of social and economic vandalism. The creators of these projects, of course, never lived in them themselves.

So what should we do? The report’s solution was simple: let’s build streets again (hence the name of their report, and of the organisation one of the co-authors, Nicholas Boys Smith, set up to promote such policies).

What the research showed, paradoxically, is that you can actually fit more people into the same amount of space if you build terraced housing, because while each tower block contains an awful lot of people, each tower block (and the low-rises you need around it to let in the light) also tends to stand in splendid isolation, surrounded by space which is in theory green and pleasant parkland but is in practice often several shades of muddy brown. Kensington and Chelsea, for example, is one of the most densely packed boroughs in the country. But it’s mostly low-rise.

The problem with tearing down these blocks is not just that it costs money. It’s that the regulations prohibit it. Targets for housing density. A ban on turning the open space between buildings into private gardens. “Best-value” tests which are skewed towards quick-fix high-rises. Rules on staircase width and steepness. Rules on weather protection and on-street parking and bike storage. Even requirements for wheelchair access – all prevent you building the kind of traditional terraced London streets that people would sell their grandmothers, their kidneys and their family pets for a chance to live inside.

And this in itself illustrates a bigger point. In a piece for the New Statesman, Jonn Elledge says a lot of things I’d agree with about our attitude towards social housing. But where we part company is where he argues that the market has failed, and so the state must step in.

That’s because the brute fact is that there is almost no area of our lives where the market has had less room to operate than our system of planning and housing. It was the state, at a local and national level, that evicted those people from the homes they liked and dumped them in tower blocks they hated. It was the state that constricted housing supply, by throttling London and other cities with green belts – and imposed the building regulations that prevent people living in homes they actually prefer. It was the state that helped to inflate the price of houses beyond the reach of would-be homeowners, both via planning policy and monetary strategy.

Similarly, one of the reasons people so often object to the new houses the country so desperately needs is because a combination of regulation, scarcity and high land prices means that the quality of the housing that’s actually built is often desperately poor or completely unsuitable. As Boys Smith pointed out in another Policy Exchange essay, “one of the key reasons we have a housing crisis is because new housing, new neighbourhoods and new multi-storey blocks are consistently, unambiguously and predictably unpopular with most people most of the time”.

Even if you ignore the actual housing market itself and just concentrate on social housing, the principle holds. One thing that unites Tory and Labour councils and planning departments, austerity or no austerity, is a brutal indifference to the voices of those actually living in the buildings they administer. The residents of these communities are not treated as customers: they are treated as irritations.

David Cameron was actually a passionate advocate of estate regeneration, even if the £140 million he put in was not what it could (or should) have been. “For decades,” he lamented, “sink estates – and frankly, sometimes the people who lived in them – have been seen as something simply to be managed. It’s time to be more ambitious on every level.”

As part of this, his team at No 10 attempted to strengthen the residents’ hand against the councils – which wasn’t just about making sure they could remain after regeneration but about insisting that they be consulted about the regeneration in the first place. Inevitably, they encountered huge resistance.

Amid the fallout from the Grenfell Tower tragedy, there will be a lot of talk about how we can make homes, particularly council homes, safer. But we should also think about how to make sure people live in the kind of homes – whether owned, rented, or provided by the state – that they actually want.