Spare a thought for the residents of Workington, the Cumbrian seaside town that now faces an invasion of features journalists trying to find out what makes ‘Workington Man’ tick.

The phrase was coined in a report by thinktank Onward, and describes a “new voter archetype” that will be crucial to the upcoming election – a white, middle-aged, non-university educated man who voted Leave in the 2016 referendum and thinks the country is “moving away from him both economically and culturally”. He also “favours security over freedom” on both social and economic issues.

Responding to the concerns of these voters, the paper contends, is the key to Conservative success across a swath of seats.

In many ways, what authors Will Tanner and James O’Shaughnessy are arguing for is actually a more specific version of Theresa May’s ‘just about managing’ agenda.

Both involve trying to refashion the Tories as the party of those outside the M25 who work hard, want to get on, voted Leave but are worried about their own circumstances, might have voted Labour in the past but are fiercely Corbyn-sceptic.

And this isn’t a bad thing – the strategic problem with Mayism was never the mission objectives set out in her first speech as Prime Minister, but the utter lack of a convincing delivery mechanism (beyond trying to turn ‘libertarian’ into a pejorative term for anyone who thought taxes should be lower).

Indeed, I would support many of the policy proposals that Will and James come up with. In fact, there’s a strong overlap with the agenda of the thinktank I run, the Centre for Policy Studies (which also set up CapX). For instance, last week we published a major piece of work on spreading prosperity beyond London, much of which is echoed in Onward’s report.

We too have called for better technical education. We have shouted from the rooftops about home ownership. There’s even an endorsement of our focus on contributory welfare.

Where I want to push back, though, is on the grand narrative – that we are moving from an age of freedom to an age of security, and that the Tory reaction should be to pump all available cash into public services rather than tax cuts.

Now, again, I buy much of this thesis. As I wrote in my book, The Great Acceleration, the faster the world spins, the more we hanker after stability and certainty.

It’s a theme I revisited recently in my paper, Popular Capitalism, when I talked about the power of ‘Take Back Control’ as a slogan – for exactly the same reasons. In that I made the point that cutting income tax to 5% won’t make people feel any better off if they don’t feel safe on the streets, or see their children trapped in failing schools.

But there are two big objections. The first is that this research is mostly a snapshot rather than a timelapse. It shows that people do want greater security. But it doesn’t really show, for my money, that there’s been some huge sea change.

The alarming findings about people wanting the army to run the country, for example, reveal a gentle long-term rise. But that’s dwarfed by the impact of the current political omnishambles.

I personally suspect that if you had asked these same questions at any point over the last few decades, you would have found that a yearning for security is pretty much always there.

Even in the 1987 election – the moment of Thatcherism in excelsis – the very first page of the Tory manifesto made the now familiar David Cameron/Boris Johnson argument that because of free-market growth, the Government could put record sums into Our Precious NHS.

In you look at the relevant section, what’s striking is that freedom and security are presented as two sides of the same coin.

On the issue of tax cuts in particular, Will and James are right that if you poll people, they say that they want to prioritise public services.

But this may be less a generational shift than an example of a well-known thermostat effect – public opinion on tax vs spend tends to oscillate fairly predictably over a period of years.

But it’s also true that just asking people about ‘tax cuts’ doesn’t quite capture the whole picture.

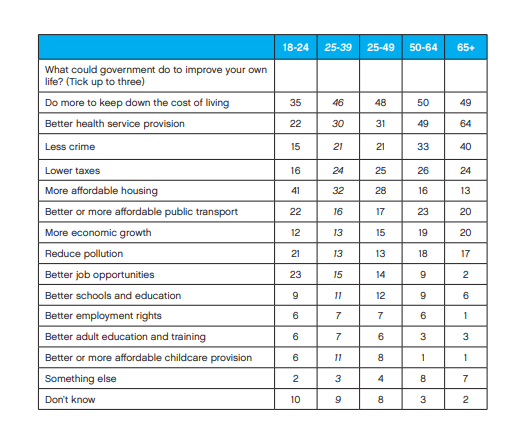

When we polled people for our ‘New Blue’ project about what government could best do to improve their own lives, the runaway overall winner was tackling the cost of living, which tax is, of course, an inextricable part of.

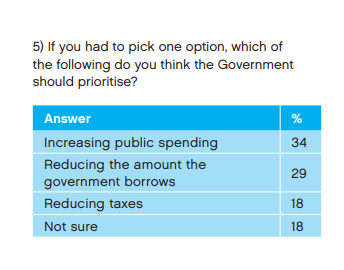

And for our report ‘Make Work Pay’, we found that reducing the deficit polls almost as well as spending more on public services.

It’s also clear that people are much more likely to think that they themselves pay too much tax than too little – something reflected in the figures about tax as a percentage of GDP.

More broadly, there’s a risk with work of this kind that you end up saying ‘there go my people, I must follow them’.

A few months ago, for example, Onward published another really big, really interesting report arguing that age is the real dividing line in politics (which is completely right).

That report said the Tories needed to focus laser-like on repairing their image among the young. This included tax cuts – which young voters were more keen on than most. So which is it?

This debate is admittedly slightly academic, as an election campaign is obviously a little too late to reconfigure your entire brand (remember Lynton Crosby’s famous dictum about fattening a pig on market day…).

But it matters because many voters tend to view policy less as a transactional thing (‘I will vote for them because they are doing this for me’) and more as an expression of a party’s underlying values.

For me, those values – for the Tories – should always include letting voters keep more of their own money. Better public services definitely need to be part of the mix, but so should doing everything possible to reward and incentivise aspiration, and promote growth.

Now, again, I should stress this is all a matter of degree. Will and James are both good people and their report does make a lot of valuable contributions. But I couldn’t run the Centre for Policy Studies if I didn’t stand up for letting people keep more of their own money as a core Conservative, and conservative, value.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.