Ahead of Sweden’s general election, all the talk was about a surge for the populist Sweden Democrats. With the final votes counted, the big surprise is how little has changed.

The two big issues at the election have been immigration and integration.

Previous elections have seen working class voters abandoning the Social Democrats for the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats. The party gained less than 0.1 percent of the votes in 1991, while it was still associated with neo-Nazi groups. It has since moved towards the centre and, by roughly doubling its voter support at each subsequent election, the Sweden Democrats gained 13 percent in the 2014 elections.

While some experts believed the Sweden Democrats could become the largest party in this election, reaching a quarter or even a third of the popular vote, with almost all the votes counted they have come in below 18 per cent.

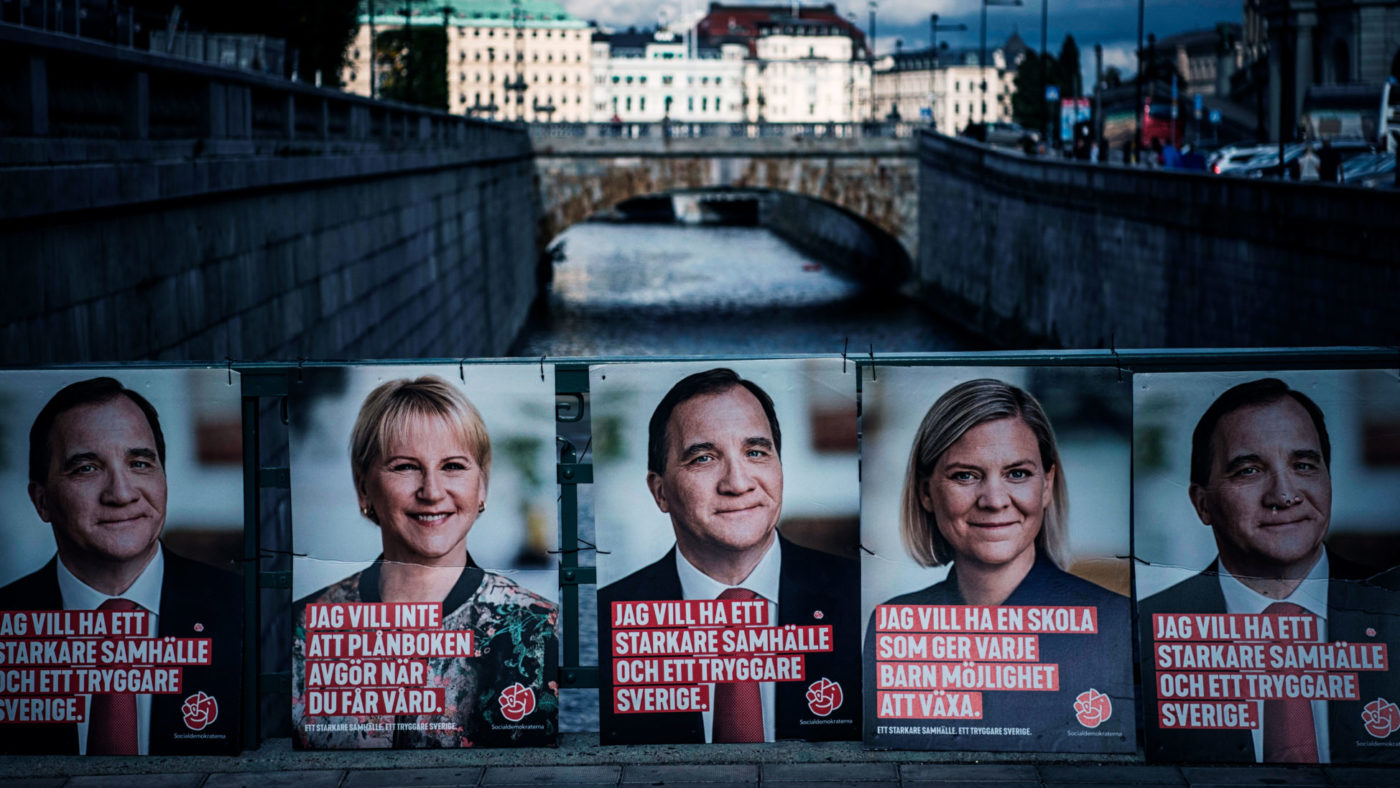

Another expected major shift in Swedish politics is the decline of the Social Democrats. This party had nearly a monopoly on governance during much of the 20th century and as late as 2002 controlled some 40 percent of the parliament. Yet, in this election, they got just 28 per cent of the vote. It was the party’s worst showing since proportional parliamentary election system was introduced in 1911, and the first time since that year that the Social Democrats have dipped below 30 per cent.

Still, the surprise is that the Social Democrats did not lose more of their working class voters to the Sweden Democrats, and in part compensated for this by attracting support from voters with an immigrant background. Stefan Löfven, the Social Democrat prime minister, will try to remain in power.

The Green party, which supports the Social Democrats, experienced a loss in voter support – nearly falling below the 4 per cent minimum to take seats in parliament. The Left Party, a former communist party which supported but did not form part of the previous government, was expected to surge ahead but gained only 8 per cent of the vote.

The liberal-conservative Moderates party, slipped from 23 per cent in 2014 to 20 per cent. Overall the four centre-right parties got 40 per cent of the vote, equal to the share of the previous government coalition parties plus the former communist party.

The non-socialist vote in Sweden has never been stronger in modern history. The issue of who will form government is difficult, since two of the centre-right parties strongly oppose working together with the Sweden Democrats. It will therefore be far from easy to gather a majority behind any government – an unusual circumstance for a country long dominated by two blocks.

What is certain is that the Swedish model has changed, and is already quite different from what international observers often believe.

In the last US election for example, Bernie Sanders had a fair shot of becoming the first US president with openly socialist ideals. The plan was simple: copy the social democratic model of Sweden and the other Nordic countries.

But Sanders was admiring a model already in decline. Even before this election, the Swedish model had undergone significant reforms. The most important of these are: tax cuts, a reduced role for state enterprises, private sector involvement in education, health and elderly care, as well as partial privatisation of pensions savings.

Today Sweden is ranked as being the 15th most free-market country in the world, above the supposedly swashbuckling Americans who are only 18th. High taxes and a large municipal welfare sector is what remains of the social democrat model not that a previously rigid labour market has been partially opened up.

Drawing on the benefits of free-market reforms, Sweden has become the EU member state with the highest share of the workforce employed in knowledge-intensive companies. Fully 9 per cent of the Swedish workforce is employed in so-called brain business jobs, that is to say jobs in fields such as tech, ICT, advanced services and the creative professions. This is nearly twice the EU average.

The public and private sectors both invest heavily in research and development. Sweden also draws on a strong Protestant business culture, which stresses hard work, individual responsibility, and punctuality.

The issue on everybody’s mind in Sweden is, however, immigration. Between 2006 and 2014, a centre-right government pushed through reductions in the generosity of welfare programs, extensive tax cuts and widened the role for private enterprises in public service provision. The government also made a deal with the environmentalist party for open border policies.

Many voters protested against these policies, and in the 2014 elections the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats surged ahead. After the vote, a minority government led by the Social Democrats took over.

Party leader Stefan Löfven initially continued Sweden’s open borders policy and proclaimed in the midst of the 2015 refugee crisis: “My Europe does not build any walls, we help each other.”

According to the OECD, in 2015 Sweden accepted 163,000 asylum seekers—a rather high figure for a country with a population of 10 million, and the highest per capita inflow into any OECD nation. The large influx, and problems related to crime in immigrant neighbourhoods, have shifted public opinion in recent years.

Integrating immigrants, many of whom have low skill levels, has also proved difficult.

Amongst adults born abroad, fully 52 per cent have very low skills in mathematics and/or reading ability. In the group born in Sweden with foreign-born parents, the same share is 21 per cent, while among native Swedes it is below 11 per cent. This massive knowledge-gap is difficult to deal with. While the foreign-born made up a quarter of Sweden’s unemployed in 2006, that figure had risen to over 50 per cent by 2017.

The challenge of integration has transformed the Swedish model. Previously, a regulated labour market was one of the core elements of the democratic socialist model. Yet, as the latest four years and the recent election shows, even the Social Democrats have largely accepted that flexibility is required in order to make it easier for those with immigrant background to find jobs.

That the protest vote has been more limited than expected might be explained by the economic policies. Although Sweden is a knowledge-intensive economy, growth is relatively sluggish. Sweden’s GDP per capita grew only at a meagre 0.9 percent in 2017, the second lowest rate in the EU besides Luxembourg. Despite that, the government has pursued policies based on cheap money, through which many families are supporting new cars and other luxuries through loans.

In 2017, household debt was at 185 percent of household incomes, nearly double compared to the beginning of the new century. If this loan bubble burst before the next election or the negative central bank interest rates are hiked significantly, many middle class families will be in deep trouble.

The second challenge is that the country’s public finances are gradually failing. Since 2002, a dozen studies have been published on the long-term survivability of the Swedish welfare state. In summary, they point out that the current model is not economically sustainable. One reason is an ageing population. The second is a gradual buildup of inefficiencies in the public sector. The wages of public sector workers have continued to increase with no commensurate rise in productivity.

Over time the famous welfare model moves towards a situation where taxes remain high, but the quality of welfare services drop. One recent paper pointed out that, between 2017 and 2025, all new jobs will have to be created in the public sector just to keep up with demand and retain the same level of staffing.

This reflects the problem of gradually rising inefficiencies, and puts the future of the Swedish model in question. The big hope is that private firms introduce innovations to make education, health and elderly care more efficient. Unfortunately the market is still heavily regulated, making service innovations difficult to introduce.

Regardless of the exact composition of the next government, Sweden will likely move towards more of the same reforms that the country has already pushed through in different waves since the early 1990s: cutting taxes and increasing the role of private enterprise in welfare provision.

The democratic socialist model is no longer what defines Sweden. The twin challenges for the future are the struggle to make integration work and the challenge of stabilising the public finances.