Stay-at-home mums have become a distinct minority in British society — that’s the conclusion of a new report out from the never knowingly under-quoted Institute for Fiscal Studies.

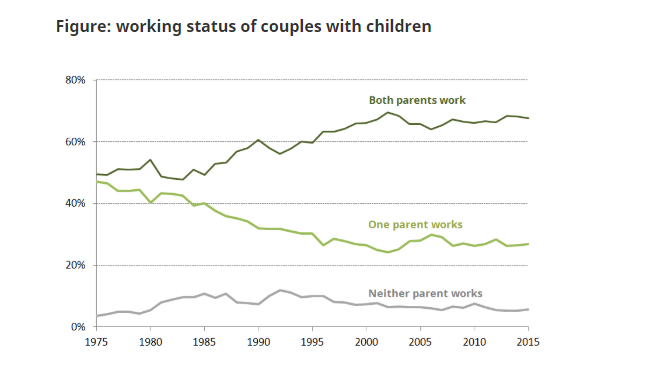

Just over a quarter of British families now feature a single earner, a number that has slumped dramatically since the mid-70s, when almost half of families (47 per cent) had only one parent in work.

As the report’s authors note, this is a “huge social change” and an obvious corollary of a sharp increase in the number of women in employment. As recently as 1975, under two thirds of women were in work, compared to last year’s figure of 78 per cent.

The research shows that the increase in working mums is driven by a very specific surge in the number of women working in their late 20s and early 30s. There has been a corresponding decline in the number of couples living together before the age of 25, and in the age at which women are having children.

It’s also worth noting just how seismic the change in educational attainment has been in the UK over a relatively short period. Of women born in the 1960s, only 13 per cent had received a degree by the age of 33. Fast forward to women born in the 1980s and the figure has rocketed to 45 per cent, with clear consequences for the type of jobs women have taken on.

These are welcome developments, but that doesn’t mean they don’t pose problems for both households and policymakers. Some households with two working parents might want one parent to stay at home, but the stifling cost of housing means they simply can’t afford to take as much time off work to care for their children as they’d like to. This is just one of the many pernicious knock-on effects of the UK’s utterly dysfunctional housing market.

What’s more, when they do go back to work, mothers of young children are liable to see a big chunk of their take-home pay swallowed up by the eye-watering cost of childcare, which is among the highest among OECD nations. The average UK nursery place now costs £122 a week, rising to nearly £150 for Londoners.

Since 2010 ministers have largely tried to solve this conundrum through subsidies, most notably David Cameron’s pledge of 30 hours free childcare for three- and four-year-olds. The problem is that offering “free” childcare forces nurseries to push up the price of unsubsidised care, adding to the higher costs already entailed by strict staff-child ratio rules.

Separate research also shows that starting a family is one of the biggest reasons for the enduring gender pay gap, with women taking time off at what is often a crucial time in their careers.

As Alan Lockey wrote on CapX yesterday, the state has been as slow to react to the surge in self-employment.

Take the statutory maternity allowance currently offered to freelancers, provided they meet some fairly basic criteria. At a whopping 50 pages, the application form seems to have been designed to rival the worst aspects of the British immigration system.

It comes to a not especially generous maximum of £140 a week, which mothers are forced to give up if they work more than 10 “keeping in touch” days over the period they are receiving the benefit. To make matters worse, any amount of work, however small, is counted as a day under the current system – so a mother could check a few emails and lose one of her ten days. This is manifestly absurd, as well as a disincentive to self-employed women to start a family in the first place.

There must surely be a better halfway house for women who want to do a bit of work while still spending most of the time with their young child.

As today’s report shows, British society has changed profoundly – that calls for government to offer an equally profound policy response.