This article is taken from CapX’s weekly briefing email. Sign up here.

Ambrose Bierce, in The Devil’s Dictionary, defined the vote as “the instrument and symbol of a freeman’s power to make a fool of himself and a wreck of his country”.

In the wake of Donald Trump’s election victory on Tuesday night, there will be many Americans who entirely agree.

The obvious parallel for the anti-establishment insurgency that swept Trump to power was the Brexit vote in the UK – indeed, it was Trump’s explicit plan to turn himself from “Mr Brexit” into Mr President.

And it’s been fascinating to see how the reaction has followed almost exactly the same script.

There was the shocked exultation of the winning side, which overcame not just the bookies’ predictions but a ruling system that seemed unapologetically biased against it.

There was the equally shocked reaction of the metropolitan elites, who had little idea – as Chris Deerin wrote in an excellent piece for CapX – of the depth of feeling lurking in flyover country (or, in the UK, outside the M25).

Next, there was the same procession through the stages of grief – the same blend of sorrowful introspection, rampant recrimination, and naked denial.

Even the grace notes were the same. There were the bathetic speeches from the incumbent leader, promising to try to make the best of an outcome they had fought against tooth and nail. And the posturing from metropolitan mayors – Sadiq Khan in London, Bill de Blasio in New York – who vowed to make their cities fortresses of civilisation amid the barbarian hordes.

There was also, in both cases, a sharp contrast between the narrowness of the vote and its long-term consequences.

Electorally, Trump’s victory, like the Brexit triumph, is being written up as the product of a seismic cultural shift – a revenge of the outsiders against the elites, a rising up of the silent majority.

But while there’s some truth to that, it doesn’t tell the whole story.

Yes, Trump won an extraordinary victory, mobilising disgruntled rural voters who simply hadn’t shown up on the pollsters’ radar.

But as Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight points out, the election was a knife-edge affair. If just 1 in 100 Trump supporters had switched to Clinton, we would all be writing solemn op-eds about how his nativist, grievance-mongering politics were always doomed to a landslide defeat.

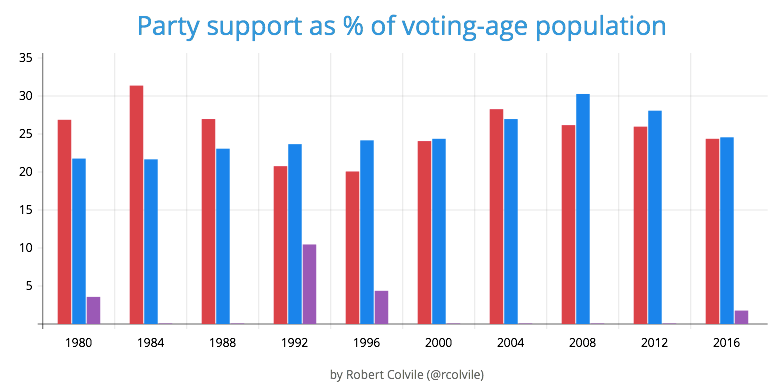

In fact, as this chart I produced shows, Trump actually attracted less support among the pool of potential voters not only than Hillary Clinton, but also Mitt Romney and John McCain:

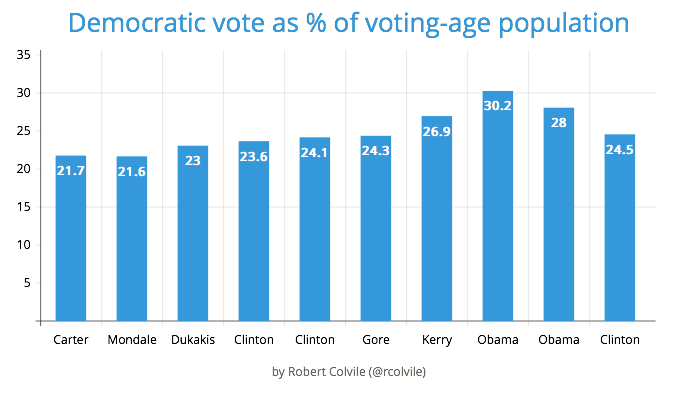

As for Hillary herself, her performance was abject – but she actually outpolled her husband Bill (who admittedly had Ross Perot to deal with in 1992).

Her party’s real error was to mistake an Obama coalition, welded together by the president’s personal charisma and appeal, for a rainbow coalition that would hand them the keys to the White House in perpetuity:

Just like the Remainers, the Democrats put their hopes in young, metropolitan voters – and were shocked to see their loyalists outnumbered at the polls by the poor, the angry and the old.

Yet the beauty (or tragedy) of politics is that it doesn’t actually matter. Both Brexit and the US election were close-run things: but now, both are settled facts.

The losers from globalisation and liberalisation have made themselves known – and now, as I pointed out earlier this week, politicians have to translate their instructions into fact.

On that score, Trump may have some very bad ideas, not least on trade and foreign policy, but he is actually in a better position to push them through than Theresa May.

She still has to worry about a Remain-leaning House of Commons and, in particular, a Remain-dominated House of Lords. Trump has a Republican House, and a Republican Senate.

As a result, in four years’ time, America will look a very different place. For starters, as Jack Graham observed on election night, Barack Obama’s every legislative accomplishment will be thrown into the historical dustbin. The Supreme Court, too, will tilt sharply to the Right.

Yet the fascination of both Brexit and Trump is that even now, no one knows quite what either one will mean, quite what form their political settlements will take.

Trump, in particular, marks a break with the past on every level. He doesn’t have the same qualifications as past presidents, the same attitudes or standards. He hasn’t been trained in the Washington way of doing things. On many issues, he’s as far from mainstream Republicans as he is from mainstream Democrats.

What we are faced with, on both sides of the Atlantic, is a situation where the nation is divided and embittered.

Yet it is also a situation where the old consensus has been thrown out of the window, where political leaders have an almost unique freedom to rewrite the rules of the game.

That may be an unnerving prospect. Yet it might also be a liberating one – so long, of course, as they listen to the right ideas.