Milton Friedman once explained how problems arise when you start spending other people’s money: “I’m not concerned about how much it is, and I’m not concerned about what I get,” Friedman says, “and that’s government”.

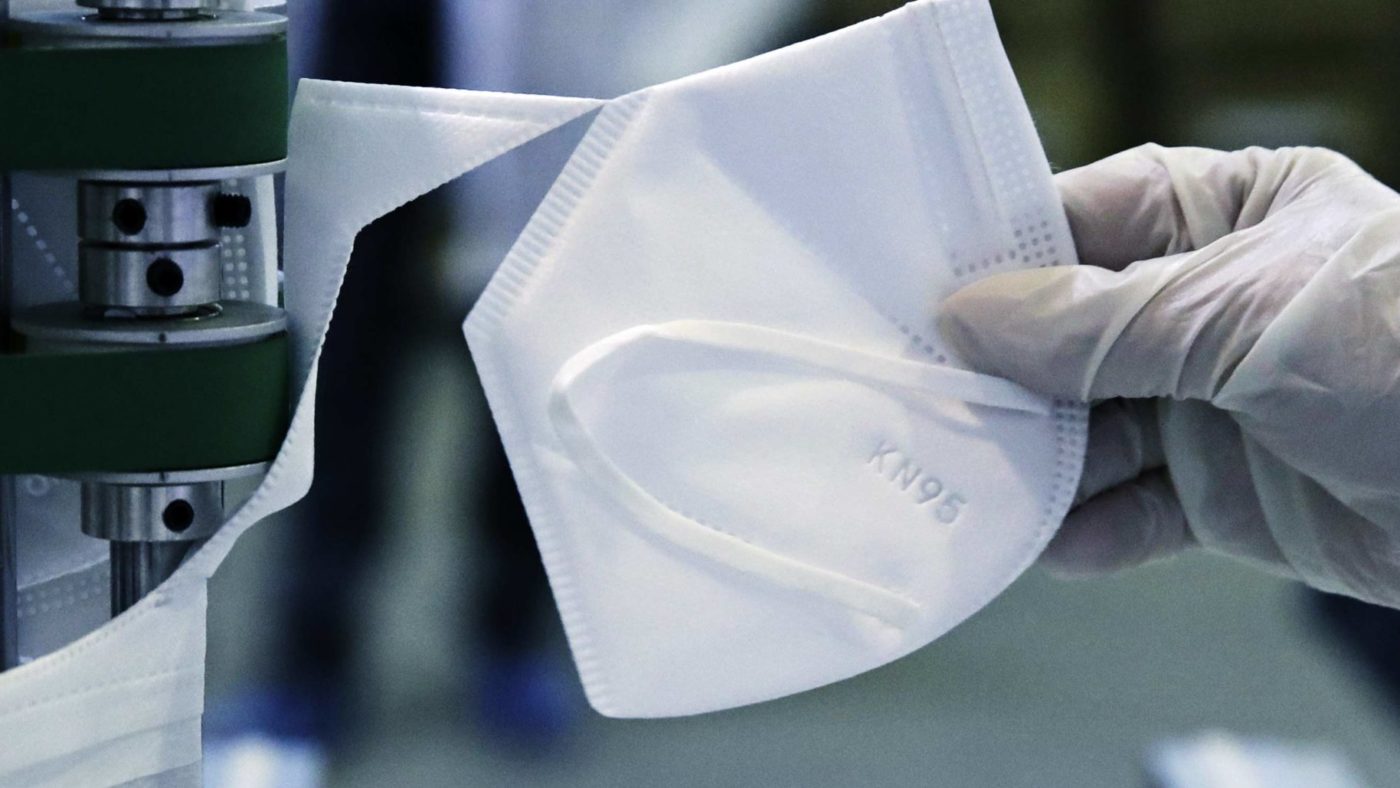

I wonder what the great man would have made of the Government using emergency procedures to award 8,600 contracts worth £18 billion in response to the pandemic between March and July this year. Four-fifths of that went on personal protective equipment.

Granted, a huge amount of money and urgency was perhaps always going to lead to some misspending. The scale, however, is breathtaking. A damning new report from the National Audit Office lays bare the scandalous lack of basic safeguards and brazen cronyism that have resulted in wasting billions of pounds.

In their rush to secure supplies civil servants ended up spending far more than necessary, without proper checks, auditing and transparency. An extraordinary £1.5 billion was spent on PPE without any basic financial and company due diligence process.

We should be sympathetic in some ways. The Government did need to pay a lot more than usual, in a competitive global market, to secure the likes of masks and gowns for doctors and nurses. Nor should we be concerned that companies “profited” by providing products to the Government, and by extension, the British people. Profit reflects the value provided by a business. For example, after Public Health England’s miserable failure to scale up testing and hostility to the private sector, it was necessary to tap Randox, the Northern Ireland-based diagnostics company, to undertake tests.

It should raise eyebrows, however, when hundreds of millions of pounds of contracts are given to businesses with connections to government without competition. The NAO found that the Government established a “high-priority lane” for PPE leads referred by parliamentarians and government officials. Those in this VIP route were ten times more likely to obtain contracts than those who applied through the normal process. Those in-the-know, the best connected, and the loudest won advantages at public expense.

For example, Ayanda Capital Limited was paid £150 million for masks that turned out to be faulty. The company had zero experience in the area, what it did have, however, was links with ministers. Meanwhile, Jonathan Bennett, an experienced textile importer, was turned down despite offering lower prices than other bidders. Even worse, much of the 32 billion items now stockpiled after the earlier spending spree will expire before they can ever be used, meaning much of spending could end up being for nothing.

While this scandal will hopefully prove unique, it does serve an important lesson about the inevitable follies of state spending. Civil servants lack ‘skin in the game’: it’s not their money, they suffer little to no personal consequence of misspending. And even if well-intentioned, they often lack the expertise and the knowledge to make the right choices.

Then comes the other side of the equation: people take advantage. Economist William J. Baumol explained how the number of entrepreneurs in a society is essentially fixed, but their activities – whether they pursue productive innovation or unproductive efforts like rent-seeking or organised crime – are determined by the respective payoffs. “How the entrepreneur acts at a given time and place depends heavily on the rules of the game—the reward structure in the economy—that happen to prevail,” Baumol writes.

In a society with a small government with few opportunities for advancement, entrepreneurs will focus on founding companies, commercialising products and improving processes: creating jobs and boosting wages. On the other hand, in a society without the rule of law, where you cannot legally do business without harassment but unlawful behaviour is unpunished, there will be more criminals. Finally, in a society with a large government, offering billions in contracts for various tasks, people will distribute their effort to get taxpayer money. This creates a class of “subsidy entrepreneurs”.

This rent seeking damages the economy because rather than expanding the economic pie these individuals instead spend their time extracting value from an ever-smaller pie. This has been supported by academic literature which finds links between higher state spending and more corruption. It is the same story for regulation: red tape offers the opportunity, and often the need, to bend rules for your benefit.

In a narrow sense, this may be rational. Businesses with corporate executives who meet with policymakers have higher profits. But it’s certainly not in the public interest. The growth in rent-seeking over the past few decades has been linked to less business creation, weaker competition and depressed wages.

This scandal should focus attention on better rules and greater transparency in government procurement. It should also serve as a reminder that the most effective way to avoid parasitic behaviour is to provide less opportunities by limiting government.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.