You can get to Cambridge from Oxford directly in a roundabout sort of way: there are 53 of them between Oxford and Bedford alone. That’s one roundabout every 2 minutes and 21 seconds. It is why the proposed £3bn Expressway from Oxford to Cambridge, with a high-speed rail line to boot, can’t come soon enough.

Lord Adonis’ National Infrastructure Commission has billed the Corridor as the UK’s answer to Silicon Valley, a high growth area linking two major knowledge areas with a highly skilled population. Not only will it benefit the two major University cities but also the towns and villages between them that currently sell themselves in units of commuter distance from London.

Yet a critical element of the plan’s success, and justification, is the building of houses: one million of them by 2050.

The corridor carved out of Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Oxfordshire, Hertfordshire, and Northamptonshire, with reach into Essex and Wiltshire, is home to 3.7 million residents in 1.54 million homes.

So that adding one million more homes, two thirds of existing stock, is no insignificant change.

For those familiar with the area, that means more households than already exist in Aylesbury, Banbury, Bedford, Bicester, Biggleswade, Buckingham, Cambridge, Corby, Daventry, Ely, Huntingdon, Kettering, Letchworth, Luton, Milton Keynes, Northampton, Oxford, Peterborough, Stevenage, St Neots, Swindon and Wellingborough combined. Even then you are short by more than 150,000 homes.

The proposal to build this many homes means we need to confront some realities about population density, housing density and occupancy rates.

It is worth noting from the start that England has one of the highest population density rates in the world. While the UK ranks 53rd, England, with 83 per cent of the UK’s population, would, if counted alone, rank 30th, with 406 people per square kilometre. That may sound acceptable, until you realise that England’s competition in the top 30 is a collection of small islands, tax havens and city states: Monaco, Singapore, Jersey, Barbados, for example; or south east Asian countries like Bangladesh, South Korea or Taiwan.

In Europe, only the Netherlands and Malta beat us, but with much smaller populations than England, which will easily outrank the Netherlands in density by 2050 anyway.

In fact, besides Bangladesh, there is no other country on earth that is both as populated and as densely populated as England. Not India, Japan, Pakistan, China, Indonesia or Malaysia.

England is two times more densely populated than Italy, over three times more than Poland, four times more than France, and twelve times more than the United States.

The people of the Oxbridge Corridor will see their population double in one of the most densely populated countries on earth.

So let’s talk housing density: the number of houses we can cram into a space.

Wixams, for example, is a new village in the corridor, just south of Bedford: 4,500 new homes, mostly faux-Victorian/Edwardian build, on a 750-acre brownfield site. At six units per acre, the village is actually built at the density of Los Angeles urban sprawl. If it is the standard we expect to build at, the Oxbridge Silicon Valley will need a building site larger than the area of Chicago.

If an American comparison doesn’t work, that’s a housing estate the size of the Isle of Wight between Oxford and Milton Keynes, and another three quarters the size of the Isle of Wight between Milton Keynes and Cambridge. It is the equivalent area of 15 Oxfords.

If we build at 1980s new-build densities, we can shrink the area of construction down to the size of 11 Oxfords. At London’s average net density (in 2005), five Oxfords. At Singapore density, just one.

So that, for all the excitement of the economic boom set to hit this hi-tech corridor, a serious and urgent conversation is needed: how do we strike the balance between 87 miles of peri-urban sprawl and a Blade Runner corridor of tomorrow’s Grenfells?

Leaving it to the chance of private developers getting what they can past a council’s local plan is to take a shantytown approach to construction.

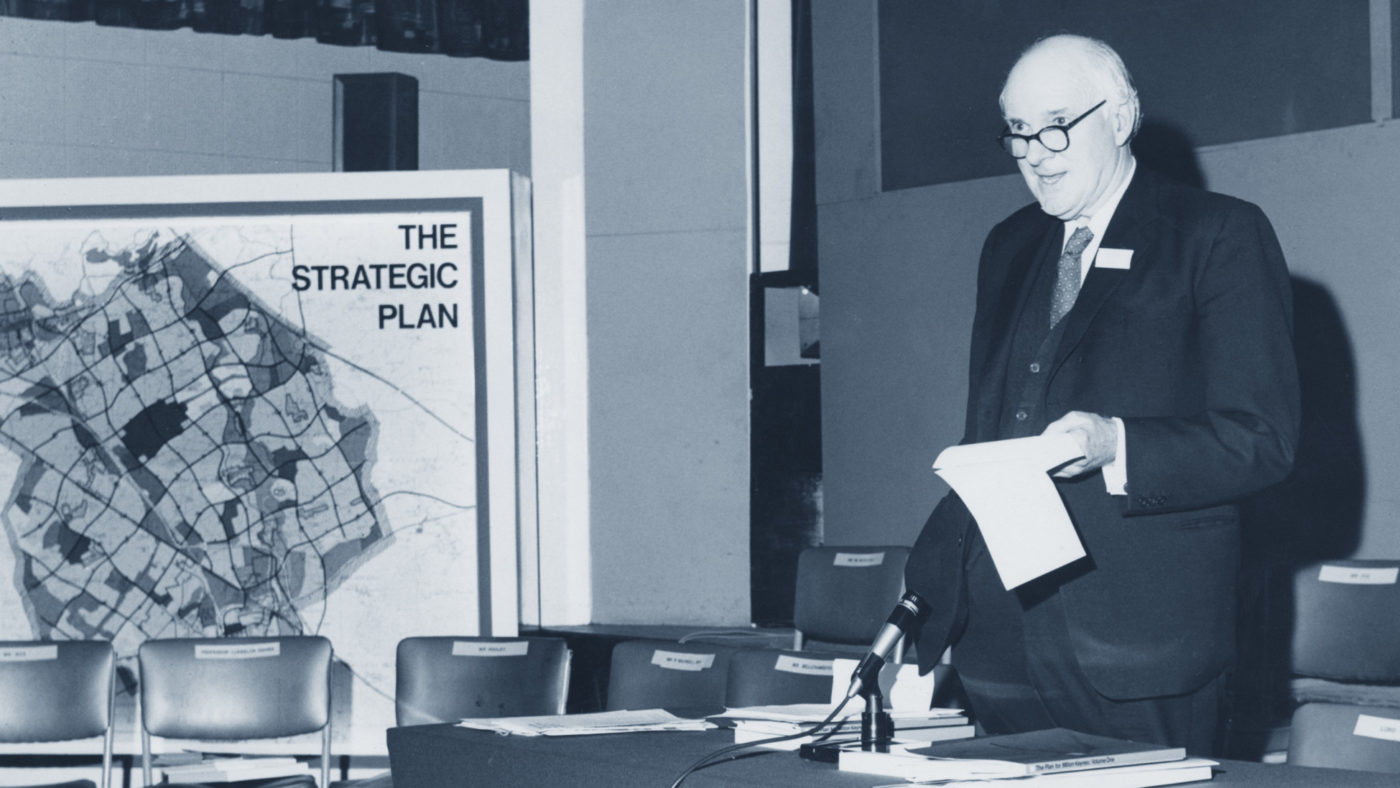

A far more ambitious plan is needed, that allows for the radical scale of construction required while managing expectations of the corridor’s current population, who have largely no idea of what is coming their way. And this will require setting style-codes while loosening consent, while taking a more centralised approach to planning for capacity – such as hospitals, schools, and leisure spaces.

We need to ask how we want to build? Up or out? A significant step could be to increase the density of our existing town centres, turning failing shops anxious about footfall into car free zones with five storey terraced flats sympathetically constructed in keeping with the Georgian, Victorian, or Edwardian architecture of a market town, furnished with cafes, libraries, shared work spaces, parks and cinemas – catering for the quarter of the population that will be aged over 65 in 2050. This way the Corridor can abound with strengthened historic towns, yet yield to the convenience of the out of town retail parks that are already flourishing along the proposed route of the Expressway, while retaining plenty of green space.

While it may be easy to grumble about immigration numbers, we do also need to take a slightly harder look at how we live our own lives. The UK has some of the lowest household occupancy rates in the West: 2.1 people per household, compared to 2.6 in the US, or 2.7 in New Zealand and Australia. This is in part because we are living longer, but is also about the changes in family formation. A growth in cohabitation, people marrying later, for shorter periods of time, and more than once, puts pressure on housing stock.

Large, densely packed populations cannot live in low-density housing at low occupancy rates: we can’t all have 4-bedroom detached houses, one for mum, one for dad.

The Silicon Valley concept is exciting. Yet there must be a visionary, attractive, and contextual way to enhance existing towns and villages to avoid it becoming a Concrete Valley. We cannot let piecemeal, slapdash building happen by stealth. Politicians, councillors, and elected mayors need to get honest with their communities and ambitious to ensure the corridor remains an attractive place to live as well as economically vibrant place to work.