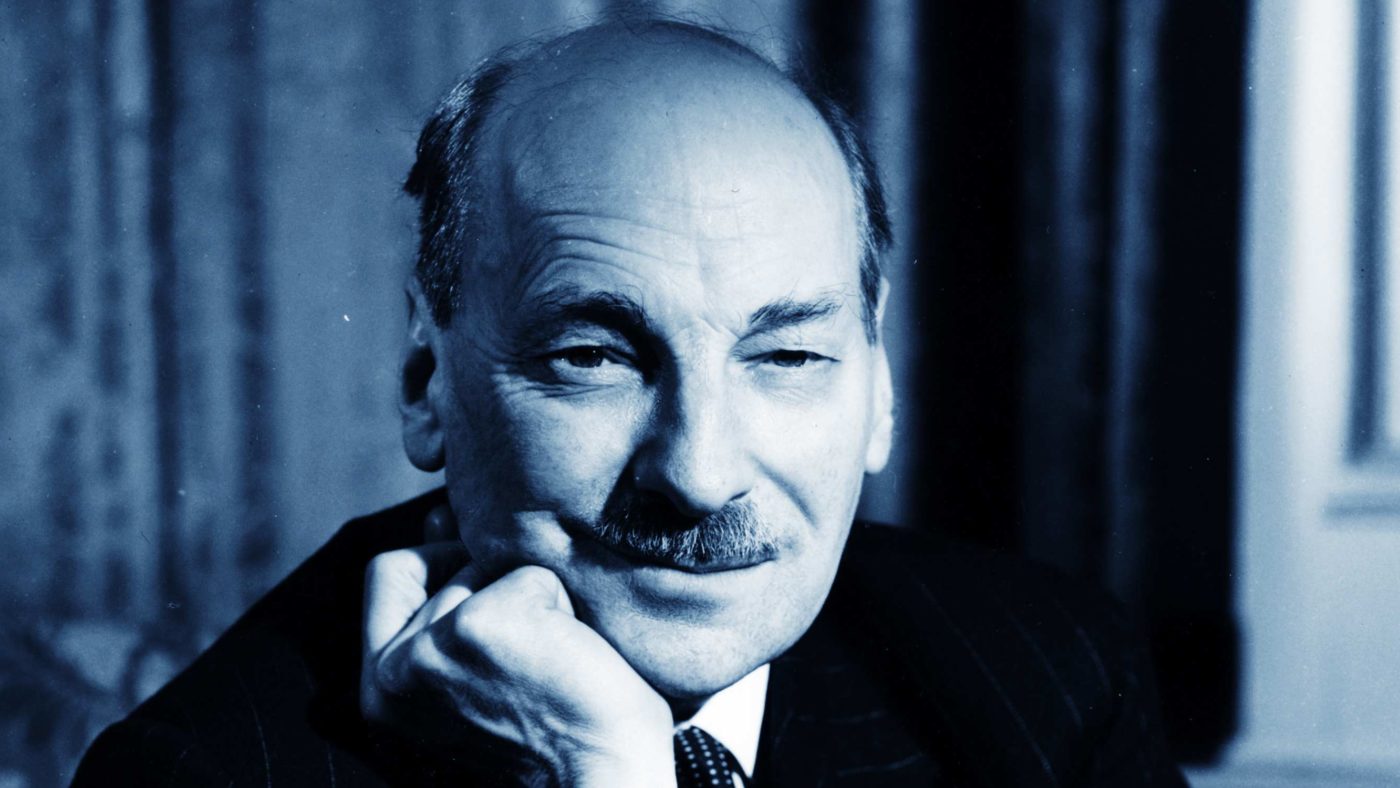

“The story of state welfare is encrusted with myths,” writes David Edgerton in The Rise and Fall of the British Nation, his new history of the UK in the 20th century. It is hard to disagree. Foremost among those myths is the British origin story that starts with the election of the Attlee government.

It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that according to this account, generosity was more or less invented in 1945, when, fresh from the unifying experience of war, Brits finally decided to take care of one another. And to do so through a system of centrally administered welfare that looked more or less like the system in place today.

The truth is a little more complicated. The welfare state wasn’t invented in 1945, but extended. Landmark developments like the creation of a National Health Service have obscured the existence of a considerable pre-existing infrastructure.

Shortly before the start of the Second World War, the total amount of public expenditure that went on social services was 8.2 per cent of national income. By 1947-8, that figure had risen, but only modestly, to 10.7 per cent.

As Edgerton puts it, “we need to refresh our sense of timing of the arrival of the welfare state… The British welfare system of the interwar years was by international standards very comprehensive, the celebrated post-war welfare state much less so.”

This is of more than just historical interest. Contemporary debates about welfare and public services are inflected with nostalgia and sentimentality.

The idea that our system of welfare was a gift that arrived fully formed in 1945 encourages a reluctance to change things. If you appreciate that the provision of welfare has evolved over time, however, you are likely to be more open-minded about what we might need to do differently in the future.

And open-mindedness is exactly what the British electorate is going to need – because, as things stand, the numbers don’t add up.

Assuming existing entitlements remain the same and there are no productivity gains, the OBR projects that spending on pensions, health, education, welfare and debt interest will rise from 26.7 per cent of GDP in 2020 to 44.5 per cent in 2067. The chart illustrating this problem is known as the “graph of doom”.

The cause of this problem is demographics. And for some, the answer is just as straightforward: raise taxes. But Britain’s tax burden is higher than it has been for nearly half a century, and there’s only so much the government can squeeze out of an economy.

The unavoidable conclusion, therefore, is that Britain needs to reassess the fundamentals of who is entitled to what and who should pay for it.

That is bound to be a difficult conversation. Thankfully, there is reason to believe it is getting easier.

For all that younger voters are written off as wide-eyed Corbynistas, they are actually more prepared for such a conversation than their older counterparts. According to the British Social Attitudes Survey, if you are young, you are a lot less likely to view “the creation of the welfare state as one of Britain’s proudest achievements”.

A healthy rate of economic growth would also help ease the tensions inherent in such a conversation. But no matter how robust the economy and how open-minded the electorate, brave is the politician who takes on the myth of ’45.