What goes on when the movie is over and the lights come up? How does the film come to be projected onto the silver screen in the first place? Step into The Flick, a run-down movie theatre in Massachusetts, and see life through the eyes of the three disaffected employees who lurk in the shadows and sweep up the popcorn after the show.

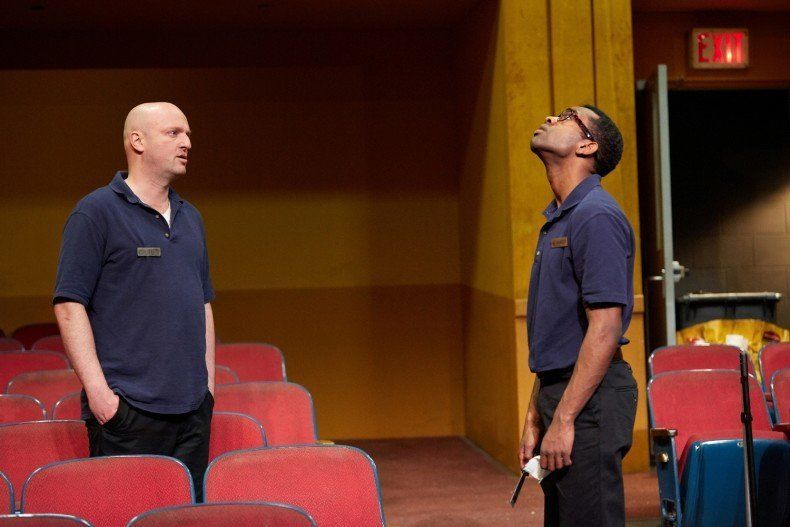

Matthew Maher (Sam), Jaygann Ayeh (Avery). Photo by Mark Douet

Annie Baker’s Pulitzer-winning play, transferred from off-Broadway to the National Theatre, gives these forgotten souls a voice they are not particularly sure what to do with. Sam is wasting his thirties in a dead-end job he nonetheless manages to find joy in. Idealistic Avery, who is taking a break from college due to acute anxiety, comes alive when discussing movies and can link Michael J. Fox to Britney Spears in six filmography steps. And Rose, the callous projectionist, has turned self-centred bitchiness into an art form.

These are not just people you can imagine meeting at a bus stop – it feels like you have met them. And as you get to know them tantalisingly slowly, in real time, the insignificant concerns and disappointments of their everyday lives become a drama as intense as the scenes featured in the cinema in which they work.

The acting is impeccable, especially Louisa Krause as Rose, who has the fewest lines and the biggest impact, fusing flippancy with vulnerability as she heads off stage mid-conversation. Jaygann Ayeh’s Avery is a depiction of deferential nervousness that never even veers close to caricature and is utterly convincing. Matthew Maher’s Sam starts off unsettling, with his disregard for polite small-talk and long unblinking stares, but becomes eminently likeable by the end. All of them carry off the Pinter-esque pauses, which can last for minutes at a time, directed by Sam Gold. At one point, Krause and Ayeh continue a scene in complete silence, seen only through the small window at the back of the theatre which shows the projector room. And still, the focus is not lost.

Louisa Krause (Rose). Photo by Mark Douet

For a play that positions its actors in an auditorium and its audience in the place of the big screen, you would expect The Flick to verge on the meta-theatrical. It doesn’t. Rather, this is an attempt at heightened naturalism, realism so real that at times it is painful to watch as the characters tie themselves in knots in ways that are familiar to us all.

There are unrequited romantic feelings, professional frustrations, and something resembling a climax towards the end. But it’s all simmering so deep that it really does take the full length of the play’s three-plus hours to bubble to the surface in a way that is thoroughly believable. Even then, it isn’t entirely clear what the The Flick is about. Is it a nostalgic homily on the lost art of film and the decreasing prominence of the movie theatre? A pointed reminder of the leagues of anonymous service workers who fall between the cracks of our busy lives? A commentary on the impersonal, take-no-prisoners pace of modern society? A critique of race, gender and class relations in twenty-first century America?

It is all of these things, and yet above all The Flick is a study in transience. The movie theatre straddles the shift from romantic 35mm film to clinical digital projection, the golden age of American cinema to today’s craze for blockbuster special effects. At the same time it provides a home for the individuals who get left behind in the upheaval. It is, as Avery implies, a form of Purgatory, and in a way, the play is too. It requires patience and stamina, and at times crosses into self-indulgence. But this is a new form of drama, thoroughly revolutionary in its acute authenticity, and worth every minute.

The Flick is on at the National Theatre until 15 June.