If the EU needs a digger to get itself out of its vaccine mess, perhaps it should call the famously Eurosceptic chair of JCB, Lord Bamford.

The background will be familiar to most. The European Commission claimed world leadership in its handling of immunisation policy, but in reality has been mired in the stagnancy of its Precautionary Principle. As the reality emerged, it blamed the supplier for not following contracts it had itself tarried over chasing, for vaccines its medicine regulator had dawdled over approving.

EU27 leaders challenged product safety based on misunderstood stats over age group testing, and again over more misunderstood stats about side-effects. The Commission put Belarus and 120 other countries on its exemption list for an export ban, but not the UK, then performed an embarrassing U-turn over introducing a vaccine hard border in Northern Ireland. Having by this point done its best to convince the EU27 general public not to take AZ, and with some countries still sitting on levels of unused stocks that they last achieved with butter, the Commission is now issuing a threat to nationalise it.

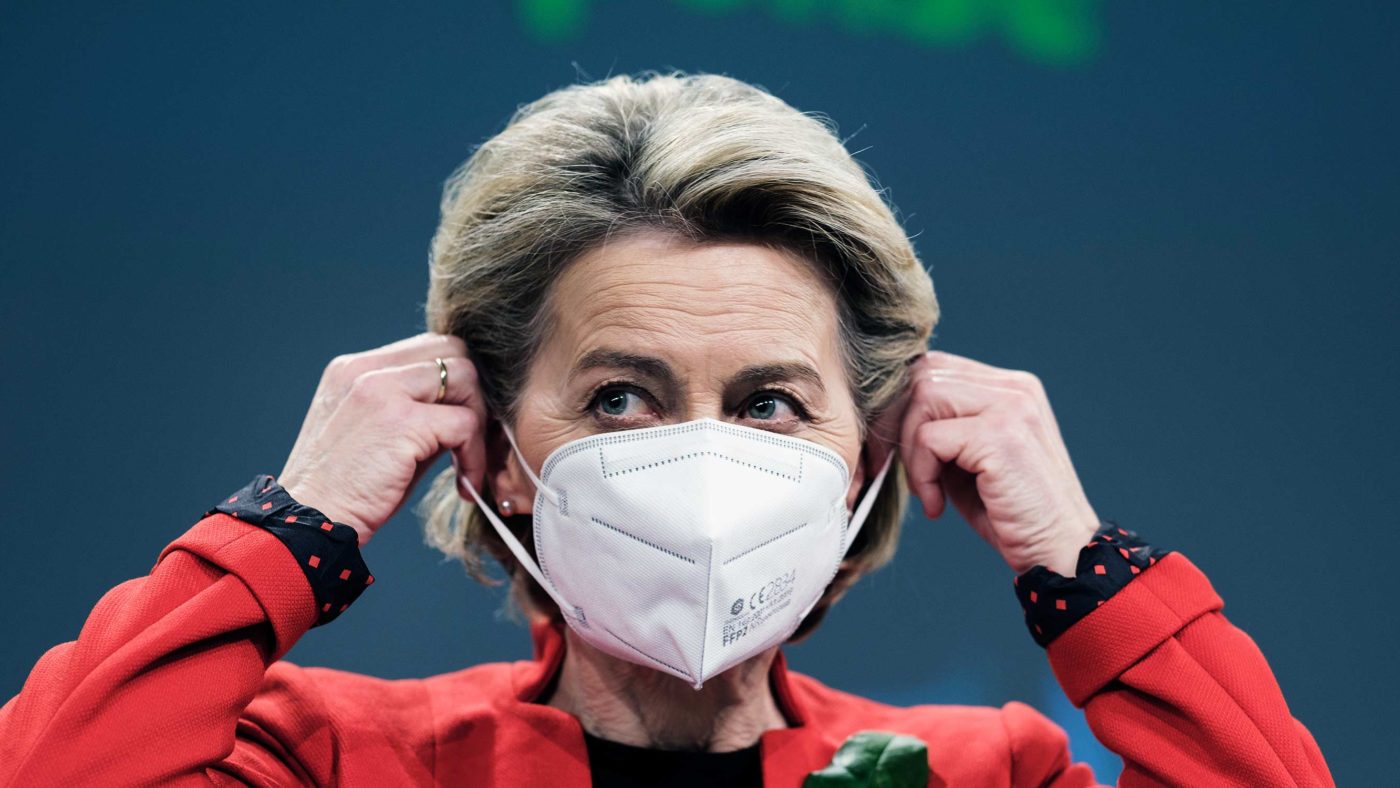

That threat is not even an honestly stated one. Von der Leyen has said that the EU could seize production of vaccines and suspend intellectual property rights, but not that they will: “All options are on the table. We are in the crisis of the century and I’m not ruling out anything for now. We have to make sure Europeans are vaccinated as soon as possible.” As broad brush arguments go, the line is not even geographically accurate. The UK’s own citizens are, self-evidently, also “Europeans”. VdL no doubt means “EU27 nationals”, but the intellectual sloppiness is telling.

The basis for any attempt to seize stock and supply would be Article 122 of the EU Treaty. Formerly Article 100 TEC, this is an emergency clause the Commission itself notes has only been used once before, during the 1970s oil crisis. A review of the text suggests it provides very weak legal grounds for corporate EU involvement today. The first part of the article contextualises the issue as relating to an economic crisis, and if “severe difficulties arise in the supply of certain products, notably in the area of energy”. This specifically frames the competency predominantly around oil shortages.

For comparison, the article is cited as the legal basis for Directive 2009/119/EC, requiring member states to establish minimum strategic crude reserves. The article’s second section does widen this to “natural disasters or exceptional occurrences” beyond a government’s control, but only in terms of the EU providing financial support. Old timers amongst us may also remember the threat of sequestering UK North Sea reserves being a feature of the 2008 parliamentary debate on the Lisbon Treaty.

The key detail in all this is that the basis has been specifically associated with energy, and not public health. The problem for the Commission is that action in that domain is via Article 168. The public health issue is firstly an area of shared competency and, secondly, doesn’t allow the Commission the obvious authority to confiscate private property: worse, it is about encouraging international cooperation, with A168.3 authorising the EU to foster cooperation with third countries as opposed to sequestering their assets.

In any event, A122 is in effect a sister clause to the infamous Article 222, the celebrated ‘Disaster Clause’ that was stretched to embroil the UK in the Eurozone bail out despite its implied and explicit exemptions – indeed, A122 was tied in then precisely because of its financial references. That detail should alert us to the Commission’s elasticity in interpreting treaty text even where there is doubt as to its legal propriety.

Such doubt here applies, with the UK now outside of the EU, and thus not part of the Council discussing the matter or able to cast a vote. I am not convinced the Commission’s legal case is watertight: it might get signed off in Brussels for political reasons but hit problems on subsequent legal challenge. I suspect the more honest legal opinions being drafted in Berlaymont right now will reflect that, even if the published ones may not.

People on stratospherically high pay scales will argue the case, but I would suggest the core issues are twofold. Firstly, any Commission ban would be legally contentious, and would be open to challenge both under the Brexit Treaty’s bilateral panels by the UK as well as by corporate appeal through the Luxembourg Courts. Neither would be a swift process, but they would be an open wound for the Commission, and the processes cannot be guaranteed to end up in its favour. Secondly, a rebuff in either venue would presumably lay the EU open to paying out elevated levels of compensation.

Clearly as Von der Leyen already admits, seizure of property requires payment to the commercial parties and possibly to the UK Government. It is striking that intellectual property is already being acknowledged as an issue, and an additional wild card question that’s not been raised is whether the original contractual terms might even allow any UK party holding intellectual copyright to rescind ‘best mates’ rates’ and inflict a penalty cost for what would amount to IP theft. That uncertainty may be bad enough, but another open question is whether any vaccine confiscation subsequently assessed to have been ultra vires potentially exposes the EU itself to lawsuits by the family of any UK Covid victim who was on the vaccination priority list and whose dose was held back. This issue is complicated and stretches into national rights under WTO law, but in the best case scenario for the EU side this is a bulk carrier of a PR fiasco simply waiting to dock.

In the anti-witchcraft treatise the Malleus Maleficarum, the author relates the story of a nun who went out into the garden. Espying a lettuce, she greedily ate it up, and was possessed. St Equitius was called in to diagnose the problem. It turned out that the Devil had been invisibly sitting on top of the vegetable minding his own business, and he complained the nun had neglected to make the customary sign of the cross to chase him away. The parallel in the tale is, shall we say, stretched; but it encourages us to reflect on the consequences and costs of intemperate avidity and irregular haste.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.