When Emmanuel Macron won the French presidency last year, his victory was heralded as the deathblow to the rise of populism in Europe. “European relief as pro-EU centre ground beats far-right” wrote the FT on its front page. “France votes for Europe” opined the Spanish daily La Vanguardia. Macron’s victory was seen as proof that the resurgence of the pro-EU centre was finally underway.

Today, that optimism appears grossly misplaced.

Europe’s pro and anti-establishment forces find themselves at loggerheads again — this time in Italy — where a political and constitutional crisis threatens the stability of both the Eurozone and the European Union.

Coming in the midst of gruelling Brexit negotiations, this latest political upheaval was unleashed on Sunday night when, in a televised statement, Italian President Sergio Mattarella announced that he was vetoing the nomination of eurosceptic economist Paolo Savona as Italy’s new Finance Minister.

Savona was the only name proposed by Italian PM-designate Giuseppe Conte to be rejected by the president, but it was enough to lead Mr Conte to give up his mandate to form a government and effectively end any hope that the Five Star Movement-Lega coalition could govern Italy.

Mattarella vetoed Savona because he says his eurosceptic and anti-euro views posed a serious risk to Italy’s economic interests. He argued that if Savona and his government were seriously considering withdrawing Italy from the euro they should have made that clear during the election campaign. Critics responded that the president had overstepped the boundaries of his mandate when he exerted political control over the new coalition government.

In a poll conducted by SWG after President Mattarella’s announcement, 35 per cent of Italian voters thought he was wrong to have not accepted the nomination. 24 per cent believe the president was constitutionally correct, but that he should have accepted the proposal given the situation. Just 26 per cent thought the decision was correct.

Whatever the constitutional legitimacy may be, both party leaders wasted no time in condemning President Mattarella and painting this as a battle between the will of the people and the machinations of a European banking and political elite.

Matteo Salvini, leader of Lega, stated that “if we are in a democracy, there is only one thing to do, give the choice back to the Italians”.

Five Star’s leader Luigi di Maio went further, accusing President Mattarella of ignoring the result of Italy’s democratic elections and calling for him to be impeached. “What’s the reason for the refusal? Because the ratings agencies were worried . . .I want this institutional crisis to be taken to parliament . . . and the president tried.” He then joined Salvini in calling for peaceful mass demonstrations against the “arrogance of the institutions”.

On Monday morning, in a move that will have further incensed anti-establishment forces, the president then tasked former IMF official Carlo Cottarelli with assembling a technocratic government to reassure bond markets and Italy’s eurozone partners.

This may be too little, too late though. The damage appears to have already been done. The president may have allayed short-term market concerns, but rejecting the Five Star-Lega candidate and appointing an IMF technocrat instead has all but guaranteed that Cottarelli’s government won’t be be approved by the Italian Parliament and Senate. That means fresh elections, possibly as soon as the autumn.

Polls conducted after Monday’s announcement already show a surge in support for Lega, giving the Five Star-Lega coalition nearly 60% of the vote.

A dangerous precedent was already set in Greece at the height of the euro crisis that shoring up the single currency appeared to trump democracy. Now, similar assertions are being made in Italy on both the right and left of the political spectrum and it is hard to see Italian voters responding well to this. These latest developments will only serve to reinforce Lega and Five Star arguments — already popular with Italians — that their vote no longer matters; that bankers and politicians in Paris, Berlin and Brussels now determine Italian political life.

It is not surprising that this latest crisis should have emerged in Rome. Now struggling to form its 65th government in 72 years, Italy is on the verge of appointing its second technocratic government in a decade, and its fifth Prime Minister in a row without a real popular mandate.

The striking difference this time though is that euroscepticism appears to have firmly taken root in Italy. Both Lega and Five Star focused very negatively on the EU and the euro during their campaigns and both performed well. This is not normal in Italian politics. The country’s fascist past and its infamous political instability since World War II have always made Italians some of the most enthusiastic supporters of the European Project.

But stagnant growth since the introduction of the euro in 1999, coupled with the procession of unelected pro-EU Italian governments and the feeling that the country was abandoned by its EU partners when thousands of refugees and migrants landed on its shores has left many Italians bitter about their country’s membership.

This rise of euroscepticism in Italy will sound only too familiar to British onlookers. Dogmatic supporters of the EU in Britain still insist that Britain’s euroscepticism is just the product of internal Conservative Party divisions, but the level of discontent with the European project across the continent shows otherwise.

It has become fashionable in Brussels, Rome and London to blame Europe’s current woes on “the rise of populism”. The glaring problem with that narrative is that most populists were nowhere near power when things started to turn sour. It is precisely because these parties can distance themselves from the crises of the recent past that they are doing so well today.

Europe’s dominant political class is worryingly unprepared to respond effectively to the rise of anti-establishment parties. Instead of addressing the reservations about national or European policies that voters are expressing in elections, their strategy is to first ignore political upstarts on the left and right, and if that fails, to then tarnish them as “populists” in the hope that, with the help of their allies in the media, this label will damage their electoral hopes.

In the echo chambers in which politicians often find themselves, the strategy may appear to work for a time, but ultimately this tactic is failing. The problem is that tainting politicians as “populists”, or their supporters as “racists” or “bigots” doesn’t absolve establishment parties of yesterday’s policy failures, nor does it successfully place the blame for today’s woes at the feet of those same “populists”.

While these emerging parties may arguably be ill-prepared or unsuitable to take the reigns of power, voters don’t yet know that to be categorically true. What they are far more certain of is that the centre-left and centre-right parties who ruled Europe through the crises of the past decade have shown themselves to be often unprepared, regularly incompetent, and sometimes corrupt.

A perfect storm of factors have slowly and relentlessly chipped away at people’s faith in the establishment in Europe today.

From persistently low economic growth to bank bailouts, rampant youth unemployment and the failure of the EU’s external borders. From the failed and expensive War on Terror, to the rise in terrorist attacks, the Dieselgate emissions scandal and mass surveillance of citizens by security forces. From corruption scandals, to unpopular austerity programmes, the loss of faith in traditional media outlets and disastrous attempts to exercise influence in Ukraine and Libya.

There are many valid reasons why a better informed, better educated, more engaged voter would today reject the consensus of the centre in search of something better.

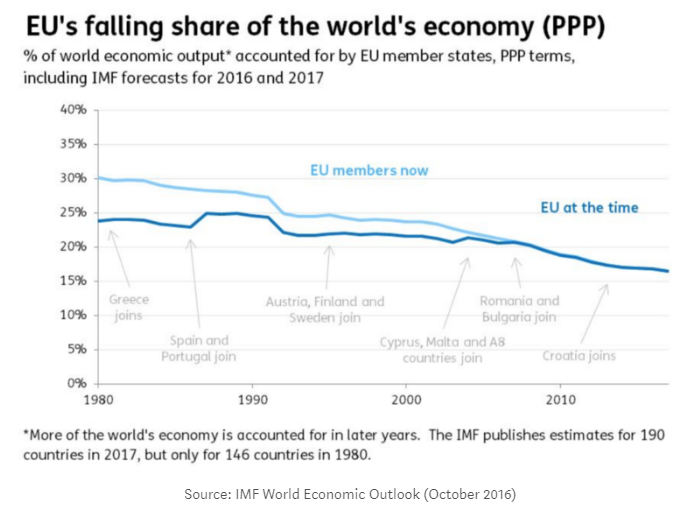

As depressing as all of these factors are though, the most worrying may be something far less sensational but all the more serious: that Europe’s dominant global role is all but over because the rest of the world is quickly catching up as the benefits of capitalism, democracy and free trade firmly take root in their regions.

This is the real crisis of the European establishment today, and to that crisis, there is no easy fix.

However, if the EU, the euro or the traditional political parties of Europe are going to survive this fundamental rebalancing of the world, they are going to have to change. They are going to have to listen to the voters more carefully. They are going to have to take that criticisms on board. And most controversially, they are going to have to instil some flexibility into the grand European project. This is tantamount to blasphemy in Brussels, but it shouldn’t be.

Jean-Claude Juncker once said “there can be no democratic choice against the [EU] Treaties”. What he meant was that certain EU constructs, such as the euro or the single market, had become irreversible and in some sense sacred. To criticise them or question their validity was now placed beyond acceptable debate, and most significantly, should be placed beyond the reach of the ballot box.

Such dogma has of course existed and survived in the past, but it usually did so by restricting democracy and dissent. To attempt to impose this reality today while still allowing democracy to be exercised at the national level was always going to lead to conflict between the people and the elite, especially when economic downturns or other crises struck.

The EU has already lost the UK and now risks losing Italy. Politicians in Brussels must step out of their echo chambers and confront their failures head on. Simply ignoring or smearing their detractors will no longer suffice.