It is now a decade since Osama bin Laden’s death, but the global threat from Islamist terrorism has not abated. Last year alone there were 13 Islamist terror attacks in mainland Europe, more than double the previous year, but most of the attackers were not affiliated with either Isis or al-Qaeda – they were driven instead by a conflict between Western liberal democratic values and their Islamist extremist ideology. This evolution of purpose should concern us all.

Increasingly, today’s violent extremists are not graduates of terrorist groups but emerge from extremist ecosystems, both physical and online, where malign far-right and Islamist groups offer kinship and empathy with one hand while meticulously polarising communities with the other. Their tactics are as obvious as they are relentless: tell people they are excluded, oppressed and marginalised, and in the most egregious instances, convince them of a future where their very existence is uncertain.

For white supremacists, their forewarning is the end of white people in a world where multiculturalism and inter-racial marriages present an existential threat to ‘whiteness’. For Islamist extremists, the existential threat is to Islam itself. Integration is framed as assimilation (‘imitating the kuffar’), while conspiracies of Western enmity to Islam are used to imply the inevitable eradication of Muslims.

The horrors of the Srebrenica genocide were repeatedly raised at one Islamist event I attended where speakers made constant references to Bosnia’s geographic proximity to the UK. So relentlessly was this point made that it went beyond reckless agitprop and took on a radicalising dimension. The audience consisted of men, women and children, all being told their faith and their families could face extinction in the UK.

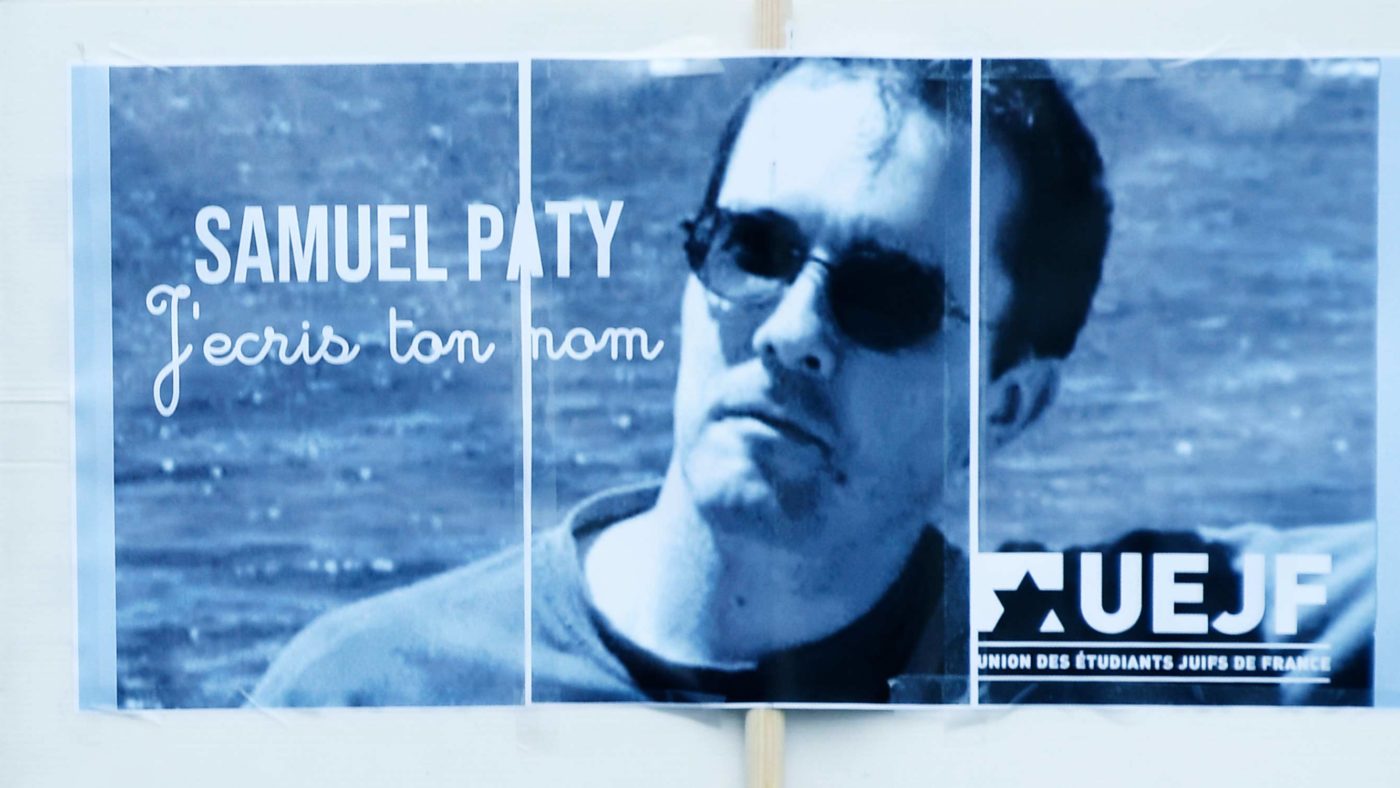

It wasn’t until the beheading of Samuel Paty in Paris that the reality of this oft-rehearsed refrain struck me. A man arrested in connection with his murder had agitated against the teacher in a viral Facebook video, telling his viewers: “If we accept this, what happened in Srebrenica might happen here”.

Intentional or not, this rhetoric has real-world consequences. Just ask Samuel Paty’s five-year old son who sat waiting that day for a father who never came home. While the act of Paty’s murder was the work of one man, it was an ecosystem of unchallenged Islamist extremism that painted the target on his back.

Closer to home, and with echoes of the tensions we witnessed in Batley, a lecturer at the University of Bristol was forced to flee his home after spurious accusations of ‘Islamophobia’ were levelled against him by the University’s Islamic Society. Unforgivably, the University has still failed to resolve this, leaving a Sword of Damocles hanging over his reputation for six months (and counting) despite some of the accusations being entirely fabricated and others swiftly dismantled by two conscientious students.

It’s striking that these activists are often peddling a version of events that is divorced from reality, as long as it achieves the aim of stirring up discord. Indeed, the pupil who first complained about Samuel Paty has since admitted she lied.

Of course, not all activists intend for their protests to end in murder, nor are they always Islamists, but they certainly anticipate their targets will lose their livelihoods, if not necessarily their lives. Either way, once they open that Pandora’s Box they cannot control how events will unfold or who else will take up their cause.

Far-right and Islamist activists have capitalised on such disputes and feed off the same duplicitous message: that Islam and the West are incompatible. Worse still, the hyper-aggressive tone of their campaigning has a chilling effect on freedom of speech, both silencing dissent and narrowing the margins of legitimate debate. After all, who would dare step out of line next time…?

Both groups of extremists do their best to reinforce a feeling of marginalisation, oppression and conspiracy in the Muslim populations of Western countries. To highlight this is not to deny the palpable existence of anti-Muslim bigotry; indeed, the forgotten casualties of Islamist agitation are Muslims themselves.

We can tackle this problem, but it won’t be easy. Our counter-terrorism efforts can pursue terrorists and help prevent radicalisation, but these are the symptoms of a deeper problem. Extremists build a following on issues that matter to many people, but we must distinguish those who genuinely value a pluralistic society from those that launder their ideology through the language of human rights, anti-racism and advocacy.

That will mean having mature, sometimes uncomfortable, conversations when secular sensibilities abrase religious feelings. It will also mean those in authority, whether it’s in Batley or Bristol, taking a much firmer line with those who seek to intimidate others or silence debate. Those who amplify these harmful campaigns should be held accountable for their complicity, while social media companies must enable the swift suppression of viral misinformation.

Ultimately, freedom of speech is not a mandate to be heard, and the intimidation that underpins so much of this discourse betrays its lack of sincerity. Ultimately, if we cannot frustrate and disrupt these ecologies of extremism, then by accident or design they will paint a target on all our backs.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.