The opening stages of the Conservative leadership election have been dominated by talk of tax cuts – and business tax cuts in particular. Quite a lot of coverage has presented this as a weird Tory fixation, utterly divorced from the real-world concerns of the British people. In fact, it’s essential to our country’s future.

Now, obviously, business tax is not the thing that matters most to people at the moment. As I’ve said in The Sunday Times, again and again and again, the cost of living is absolutely the key issue in British politics, and absolutely the thing the campaigns need to have an answer on. That answer might even involve letting them keep more of their money!

But as I said on the BBC yesterday, there’s another aspect of the tax system that needs urgent attention.

Work by the Centre for Policy Studies (which I run) and the US-based Tax Foundation has shown that we are heading towards a business tax cliff edge.

In spring 2023, the expiration of Rishi Sunak’s super-deduction and the 6pt rise in corporation tax from 19% to 25% means that it will suddenly become a lot harder to do business in Britain. We will plummet down the Tax Foundation’s global Tax Competitiveness Index, ending up with the 31st most competitive business tax regime out of 37 OECD nations. (And the 30th in terms of overall taxation.)

The Index measures how growth-friendly our tax regime is. And we’re on course for a relegation position. That’s even worse for us than for others because our economy depends more than most on attracting overseas investment, which in turn raises growth, productivity etc.

In our recent CPS paper ‘Why Choose Britain?’, we interviewed more than 100 major investors about how to make the UK a more attractive place to do business. A lot of them talked about certainty, stability, rule of law, the attitude of government etc. But they also talked about the importance of corporation tax rates, which act as a huge signal to investors and entrepreneurs.

As George Osborne said when he started cutting the rate from 28% to current 19%: ‘We live in a world where the competition for business is growing ever more intense. I want a sign to go up over the British economy that says ‘Open for Business’.’

That’s one of the reasons why, when Boris Johnson appointed Nadhim Zahawi as Chancellor, cancelling the corporation tax cut was one of the big measures they agreed to announce – before the Government fell apart the next day. (And yes, they had been reading our paper.)

But it’s not just about the signalling effect.

Research by the OECD has shown that of all the different forms of taxation, taxes on business and investment have the worst impact on long-term growth.

This is utterly unsurprising. Capitalism is ultimately, as the name suggests, about capital. The more capital you have, the more growth you create. So as we pointed out in our recent review of the UK’s tax system, the most growth-friendly approach is to focus taxes on consumption rather than investment: to tax the harvest rather than the seed corn. (In fact, one of our big problems as a country is that the most popular tax rises – on business – tend to be the most economically harmful, and vice versa.)

As we’ve said in past CPS papers, the central estimate from the academic literature is that FDI falls by 2.5% for every percentage point rise in the corporation tax rate. An Oxford University study found that nearly 50p of every £1 increase in the corporate tax burden falls on workers, in the form of lower wages. And evidence from the US suggests a 1 percentage point increase in the corporation tax rate is associated with a 3.7% decline in employment in start-ups. (There’s plenty more in this vein – see eg this from Sam Bowman.)

These nasty side effects also mean that increasing corporation tax will not make as much money as the Treasury hopes. Back in 2013, HMT estimated that ‘within 20 years, 45–60% of lost corporation tax receipts would be recouped through increased economic activity’. In 2017, the IFS said that was still a sensible projection.

But by the same logic, a corporation tax rise should result in a similar reduction in economic activity, lowering the amount raised and – more importantly – leaving us a smaller economy than otherwise.

Also, bear in mind that the original forecasts for the increase in corporation tax to raise £12bn, rising to £17bn by the end of the parliament, were in a world where the recovery from the pandemic was in full swing – and indeed where the US was also planning to whack up corporate taxes to pay for Biden’s spending bonanza.

Not only will the receipts now be lower than envisaged, but the economy is more vulnerable – and the international environment less sympathetic.

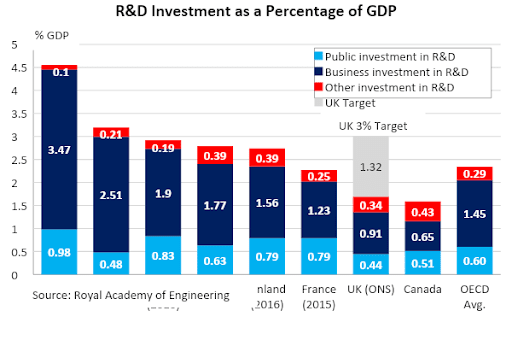

And there’s another issue here – business investment. This is core to our productivity problems and lack of growth, and something where we’ve had a longstanding problem.

We’re also extremely poor at turning R&D spending into growth. (It’s not a coincidence that these were the issues Rishi Sunak was zeroing in on while Chancellor – see for example his very good Mais Lecture.)

Some people have argued that the problem with Osborne’s corporation tax cuts was that they didn’t move the needle on business investment. So putting corporation tax up won’t do any harm, or at least will do less harm than it might.

This is misleading, for several reasons. First, taking something down by nine points over eight years is not the same as putting it up by six points overnight – especially at a time when the economy is in an extremely precarious state.

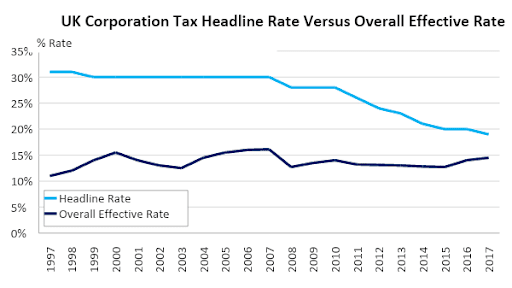

Second, Osborne paid for his corporation tax cuts by sharply reducing investment incentives, among other revenue-raisers (in particular extra taxes on the banks). In fact, by the end of his tenure his business tax rises were making back as much money as his corporation tax cuts were costing.

As a result, even though the headline rate of corporation tax fell, the actual proportion of tax companies were paying as a percentage of their profits remained almost exactly constant.

So the obvious rejoinder to people saying ‘corporation tax cuts didn’t do much good’ is that we didn’t really have enough of them to move the needle – whereas the coming corporation tax rise certainly will.

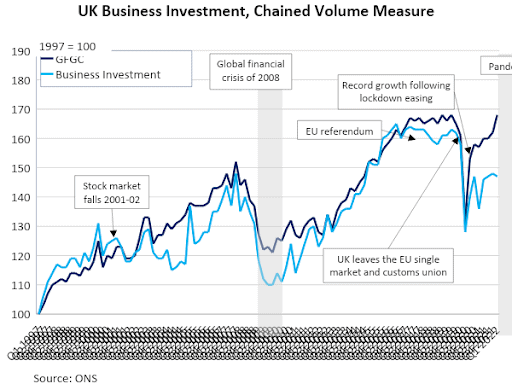

But actually, even with these countervailing effects, the Osborne era DID see a recovery in business investment. As this chart shows, as headline rates of corporation rates start to come down, it picks up more and more quickly, at rates never seen in the Blair years – until being derailed by Brexit, or rather the whole British political class spending three years tearing lumps out of each other, amid the looming threat of a turbo-socialist Labour government.

And then in 2019, just as normality resumes, we get the pandemic.

Because I’m just that interesting, I spent a full afternoon last week looking over OECD data on Gross Fixed Capital Formation, of which business investment is the preponderant component. It turns out that under Cameron and Osborne, the UK had the second highest rate of business investment growth in the G7, only narrowly behind the United States. Even when you take account the wasted years of Brexit squabbling, we still come out second overall among the big Western economies.

Gross Fixed Capital Formation Growth Rankings

| 2010-22* | Position | 2010-15 | Position | 2016-22* | Position | |

| Canada | 2.1% | 4 | 3.3% | 3 | 1.0% | 6 |

| France | 2.0% | 5 | 0.8% | 6 | 3.1% | 2 |

| Germany | 2.2% | 3 | 2.7% | 4 | 1.7% | 4 |

| Italy | 0.5% | 7 | -3.0% | 7 | 3.8% | 1 |

| Japan | 0.8% | 6 | 2.1% | 5 | -0.5% | 7 |

| UK | 2.4% | 2 | 3.7% | 2 | 1.2% | 5 |

| USA | 3.7% | 1 | 4.4% | 1 | 3.0% | 3 |

| OECD Avg. | 2.5% | – | 3.0% | – | 2.0% | – |

*Q1 2022 only

This is all the more impressive since it came at a time when Osborne was slashing government investment, meaning that the private sector had to do even more of the heavy lifting.

Now, there’s an important caveat here. The argument from Rishi Sunak, while Chancellor, was a) that corporation tax going up was a regrettable necessity (to pay for the pandemic/all the billions Boris loved throwing out the door) and b) that the real growth effects would come from better business investment incentives.

That’s a perfectly legitimate argument. Either abandoning the corporation tax rises or bringing in a permanent super-deduction style full expensing regime – of the kind suggested today by Tom Tugendhat in his own campaign launch – would do wonders for our score on the Tax Foundation’s Tax Competitiveness Index. In an ideal world, we’d do both.

In fact, if the leadership election hadn’t happened, we’d have been publishing some modelling this week showing the economic benefits of various full expensing options. (Campaign policy teams: my DMs are open if you want the details.)

Of course, these aren’t the only problems with our business tax regime. Our recent report on the Online Sales Tax highlighted the glaring flaws in the rates regime, and the enormous damage it is doing to the high street. Not least of the problems is that we’re trying to extract more cash from our retailers than any country in the OECD apart from Israel. No wonder Labour has made this a core campaigning issue.

The point is, the leadership candidates absolutely need to focus on, and have an answer on, cost of living pressures. The cost of living crisis will and should be the main focus of their administrations.

But whether it’s improving investment incentives, or helping high streets, or abandoning the corporation tax rise (or even cutting it further), the business agenda and its prominence in the campaign isn’t about a weird Tory preoccupation with tax cuts. It’s about our ability to create jobs, grow the economy, and attract investment.

Yes, we need to make sure the reforms proposed are something we can afford. But making Britain a better place to do business is something we desperately need. And it’s great to see that issue, on which the Centre for Policy Studies has been banging the drum so consistently, come to the fore during this campaign – and get such wide acceptance from the candidates.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.