It’s not exactly news that Donald Trump is a fan of Twitter. Indeed, his handlers must often wish that they could tear the keyboard from his hands, as they wake up to find that their insomniac candidate has been firing off messages urging the world to check out a Miss Universe’s candidate’s (non-existent) sex tape:

Did Crooked Hillary help disgusting (check out sex tape and past) Alicia M become a U.S. citizen so she could use her in the debate?

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 30, 2016

Throughout the campaign, Trump has been using his tweets as the equivalent of Molotov cocktails, lobbing them into the debate and then gleefully documenting the ensuing explosions.

But what about the words, the language? What kind of messages, consciously and subsconciously, was he sending out about his political priorities, about his campaign strategy, about the kind of president he would be?

Rather than going through Trump’s messages one by one, I decided to try something different. Twitter allows you to bulk-download a user’s most recent tweets. I took that data for both Trump and Hillary Clinton, stripped out the dates, and analysed the raw text (dating back to January in Trump’s case and April in Clinton’s, because of her higher volume of tweets).

The result, it turned out, was fascinating – perhaps the closest thing you can get to putting both campaigns on the couch.

This election is about one thing above all – Donald J. Trump

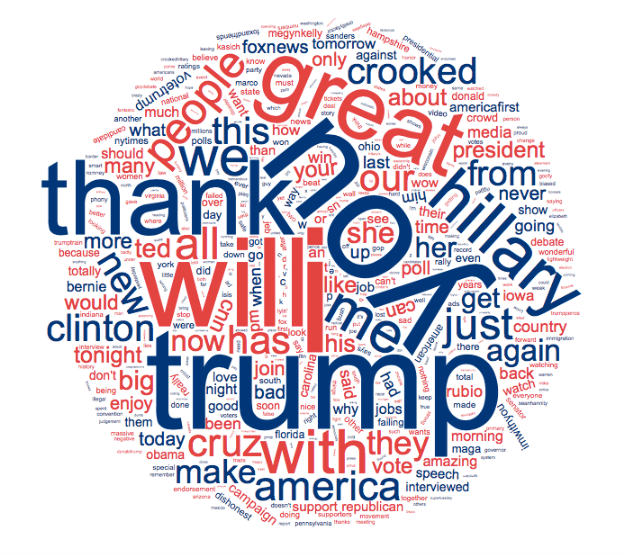

The image below is a word cloud of the language Trump uses (with a few common words such as “the”, “and”, “to” etc stripped out).

It’s no surprise that his own name features heavily – not just in endorsements to “Vote TRUMP!” but in references to Trump Tower, Trump’s golf course at Turnberry and, of course, Trump tacos.

It’s no surprise that his own name features heavily – not just in endorsements to “Vote TRUMP!” but in references to Trump Tower, Trump’s golf course at Turnberry and, of course, Trump tacos.

Happy #CincoDeMayo! The best taco bowls are made in Trump Tower Grill. I love Hispanics! https://t.co/ufoTeQd8yA pic.twitter.com/k01Mc6CuDI

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 5, 2016

Yes, Trump often mentions his opponent. But “Hillary” crops up just 339 times in the 3,092 tweets I trawled through (coupled, on 182 of those occasions, with “Crooked” – plus another 21 appearances for the hashtag #crookedhillary).

“Trump”, on the other hand, appears 697 times – and his Twitter handle, @realdonaldtrump, another 290 (usually when he is retweeting a message of support).

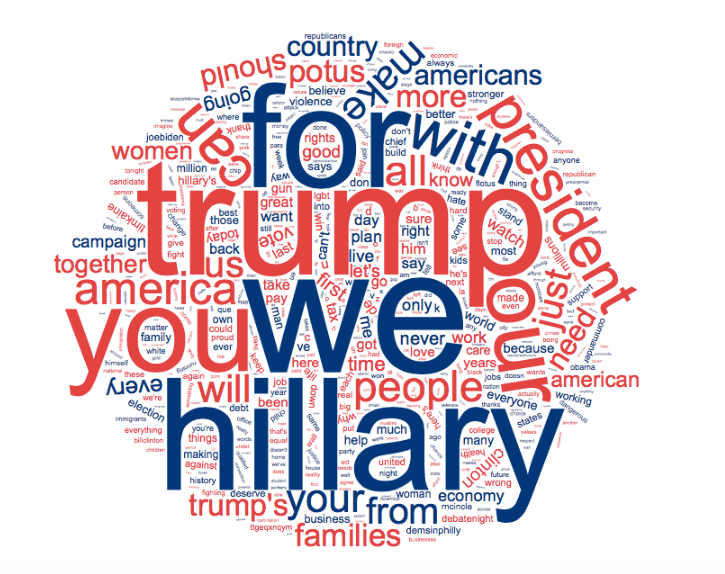

Now take a look at the word cloud for Clinton:

Of the 2,624 tweets I scraped, “Trump” appears 646 times – more than “Hillary” on 623. The disparity becomes even greater when you consider that Clinton doesn’t even make a pretence of running her own account. This means that many of the uses of “Hillary”, perhaps even most, come from her staff putting out a quote from her latest speech or press release and tagging her name on at the end, for example:

"It’s wrong to take tax breaks with one hand and give out pink slips with the other." —Hillary

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) July 29, 2016

The two campaigns, in other words, have one thing in common: they want to make Trump the overwhelming focus of the campaign.

Trump is an egotist. Hillary is a collectivist

There has always been a view in American politics that the Republicans are the party of the individual and the Democrats are the party of the group. But the nature of the two candidates this time has led to each making a sharply different appeal to the electorate – and to offering a sharply different vision of what the presidency is for, and what kind of president they will be.

With Trump, for example, the word he reaches for the most often (apart from “the”, “to”, “a”, “and” etc) is also the most obvious: “I”. For Clinton, the list is topped by a very different word: “We”. The definitive Trump sentence, coupling his favourite pronoun and his favourite verb, is “I will”. The Clinton equivalent is “We can”.

These are not subtle differences, but yawning linguistic chasms. Trump uses “I” 870 times, and “we” just 276. For Clinton, the figures are 363 vs 711. Trump uses “We can” just 13 times, but “I will” 190 times (although admittedly, many are to say “I will be on Fox and Friends” or the equivalent). Hillary says “I will not declare war on an entire religion”, but is far more likely (by 115 to 28) to be found saying “We can never let Republicans cut or privatize Social Security”.

There is an interesting thesis to be written on what this says about male and female gender roles, and leadership styles. But whatever the explanation, it permeates the campaigns and their strategies.

Take a look, for example, at the banners for each candidate’s Twitter page. Trump gazes inscrutably towards his 12 million followers, projecting an image of messianic implacability:

Hillary’s account, by contrast, has the candidate captured in rictus grin, with a short biography that gestures in the direction of comedy but appears equally concerned with identifying her with specific electoral interest groups. The banner image is not a picture of Clinton herself, but a (non-white) hand holding a placard marked “Together”:

When it is not attacking Trump, Clinton’s Twitter account is, by and large, a laser-guided attempt to appeal to these particular interest groups, and to draw them together in support of each other.

There are tweets in Spanish, messages to little girls, or to nurses, or immigrants, promises to defend civil rights, workers’ rights, voters’ rights, women’s rights, LGBT rights and the rights of the disabled. Often, these promises are made simultaneously:

Civil rights & voting rights.

Worker’s rights & women’s rights.

LGBT rights and rights for people with disabilities.Let's defend them all.

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) April 27, 2016

Then there are messages about women’s health care, paid leave, child care, the minimum wage. In short, if you belong to any particular non-white, non-male, non-wealthy section of the electorate, Hillary has you covered. There are 129 uses of “families”, 121 of “women”, 42 of “kids” and 26 of “children”. “Troops” and “soldiers”, by contrast, crop up three times between them. (Hillary does use “security” 20 times, but it’s as likely to be the social kind.)

And what of Trump? The contrast between her focus-grouped coalition and his personalised movement is clear. “Women” appears 43 times – normally in rebuttal to Hillary’s attacks on him. “Families” crops up only 12 times, usually coupled with condolences to those affected by a particular disaster. There are eight uses of “children” and seven of “kids”.

Trump, in other words, doesn’t use Hillary’s signifiers. But nor does he replace them with his own. His Twitter stream is relentlessly solipsistic. Remarkably for a Republican candidate, Trump does not pay any kind of tribute to America’s “soldiers” or “troops”, and never refers to himself as a potential commander-in-chief – almost all the uses of the word refer to an NBC forum that uses the phrase. Hillary, by contrast, uses the phrase 35 times – invariably to stress her own readiness for the role and cast doubt on Trump’s. And even though he’s running on promises to save the economy, he uses the actual word far less than Clinton does. Indeed, going down the list, jobs (70) is the first word to be linked to a particular policy priority, and that comes well behind “poll” on 96.

Trump, in other words, is about making America great again (459 uses for “great”, 245 for “#makeamericagreatagain, 56 for “#MAGA”) – not the details about how it will be done.

The Twitter accounts are the campaigns in miniature

The more you look at these accounts, the more it becomes glaringly apparent that they confirm every cliche about the candidates and their campaigns. Clinton’s Twitter account is far more organised, disciplined and strategic – and far less personal, not least because she has delegated it to her team. Key words and key messages crop up again and again and again.

Yet it’s also, like its candidate, rather worthy and dull. Apart from the entertaining jabs at Trump, there’s a sense of focus-grouped piety to many of the pronouncements: “Very concerned about the outage in Puerto Rico and the millions of families who don’t have power”, “Going to bat for kids who are too often counted out has always been a priority for Hillary”, “Tim Kaine is more than just a great running mate – he’s a great guy to have as a friend, too.”

Trump’s account, by contrast, is a great big barrel of crazy. The punctuation and capitalisation are all over the place. He can’t seem to decide whether he wants to Make America Great Again or #makeamericagreatagain or simply #MAGA. He can’t even use apostrophes – witness this tweet in the wake of the Brexit vote:

Self-determination is the sacred right of all free people's, and the people of the UK have exercised that right for all the world to see.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 24, 2016

But there’s also a delirious energy to the account, as it pinwheels between announcing rallies and interviews, boasting about the latest polls, blasting away at Trump’s opponents, and thanking those who have come out to see him. In the sample of tweets I studied, Trump used 2,387 exclamation marks. Hillary could muster just 89. And Trump makes far greater use of the word “join” – 108 to 31. She feels like she’s sending out press releases; he feels like he’s rallying a movement.

Trump truly is obsessed with the media (and with himself)

I mentioned above that Trump fails to pick out particular groups in his tweets in the way that Hillary does. That’s not entirely true. The man is astonishingly, unbelievably obsessed with his own media coverage – his appearances, his reviews, how dumb and stupid people are who say nasty things about him.

If he’d tweeted once more about how much he hates CNN’s coverage of him, Trump’s use of the station’s name would have actually tied the number of times he’s used the word “vote”, at 109 – and a few more tweets would have seen him eclipse “President” at 112.

As mentioned above, he’s also obsessed with polls (98), Fox News (124), the media generally (81), Megyn Kelly (53), the New York Times (47), Fox and Friends (35) and, of course, ratings (35).

Given how much time he seems to spend consuming this stuff – or bad-mouthing shows which he insists he hasn’t watched – it’s remarkable that he still finds time to campaign to be President. It’s also a hint about what his priorities might be if elected, especially since “Isis” gets 37 mentions and “the wall” just 15.

…But he prefers compliments to insults

Trump is a master of the political insult. There are the single-tweet howitzers or the deployment of a jabbing, repeated insinuation, for example that Hillary lacks stamina, perhaps because of her unspecified health problems:

Hillary Clinton only knows how to make a speech when it is a hit on me. No policy, and always very short (stamina). Media gives her a pass!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 26, 2016

But actually, for all that Trump throws around words like “dishonest” (51 uses), “sad” (40) and “rigged” (27), he doesn’t tend to stick with one particular line of attack: the word “Benghazi” only crops up five times, “emails” only 11 and “deleted” only four. (Perhaps this is because he knows the media will take and amplify his original charges: he only has to set the hare running.)

Trump’s favourite insults

“Crooked” – 182 uses in 3,046 tweets

“Bad” – 94 uses

“Failing”/”Failed” – 83 uses

“Dishonest” – 51 uses

“Sad” – 40 uses

In fact, Trump overwhelmingly uses his Twitter account not to attack, but to thank – to thank the crowds at his rallies, the supporters who have voted for him, the interviewers who asked him fair questions. All told there are 508 uses of “Thank you” in his Twitter output for the months in question.

Thank you Council Bluffs, Iowa! Will be back soon. Remember- everything you need to know about Hillary — just #FollowTheMoney. pic.twitter.com/Z6FQ3aXdEA

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 28, 2016

It fits in with what is, for both campaigns, the overwhelming purpose of their social media activism: to drive engagement. These messages do not exist in isolation. The idea is to use the pictures and links to amplify the chosen themes, or to draw readers into increased support, converting them from interested into committed.

Both parties are moving away from the centre – and from the free market

A candidate’s Twitter account is, primarily, a device for addressing the converted – the millions of people who have signed up to be their supporters, rather than undecided voters in the centre. Yet it is also a megaphone that can be heard more widely, one amplified by news coverage and retweets by those from other parts of the political spectrum.

And what is particularly striking is the way that, in both camps, that megaphone is being used to deliver populist, statist messages of a kind that, even four years ago, would have been anathema to both parties.

Back in 2012, Barack Obama boasted about how he had cut taxes for middle-class families and small businesses (a claim which PolitiFact ruled “mostly true”). His Democratic successor has used the word “tax” or “taxes” 74 times on her Twitter account.

But the overwhelming majority of these are complaints that Trump wants to “give trillions in tax breaks to people like himself”, or Bernie-Sanders-inflected demands that Trump, or Wall Street, or “the wealthy” pay their “fair share”.

Trump's calling for trillion dollar tax cuts for Wall Street.

It's time for them to pay their fair share. https://t.co/y8vyESIOES

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) September 12, 2016

Of course, governing is not campaigning – and every president must make accommodations once they get to power.

But even the most cursory analysis of the Trump and Clinton campaigns’ use of words, the slogans they pick and the symbols they choose, shows that they appear (Trump rather more than Clinton) to view the economy, and society, as a zero-sum game.

The messages that they choose to focus on, that they put out again and again, promise their favoured voters not so much that this will change, but that they will become the winners.

That hardly seems like the best of recipes for making America great again.