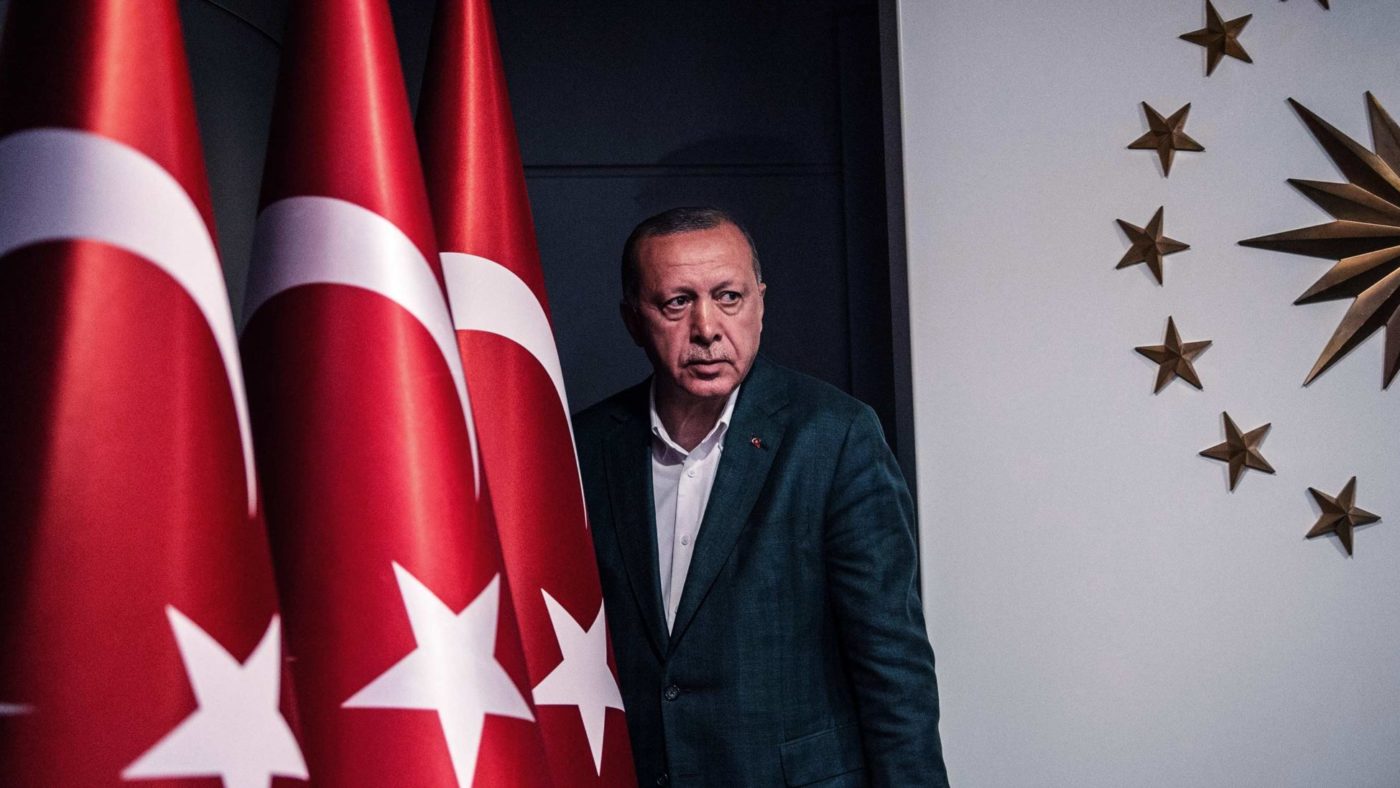

Turkey’s falling out with Australia and New Zealand since the Christchurch terrorist attacks is a reminder of the distance that has opened up between Ankara and Western capitals. And that gap is only increasing. Whilst Turkey remains a member of NATO and is negotiating its accession to the European Union, its illiberal tendencies and its leader’s worldview make it appear increasingly ill-suited to both.

Whilst Western politicians were pressing social media companies to take down footage of the massacre at the Al-Noor mosque, the President of Turkey was to be found playing it on giant screens at election rallies. His message was abrupt – Muslims are under attack, and the West is and always has been responsible.

In linking Christchurch to the battle at Gallipoli, an event of enormous reverence to Australians and New Zealanders, Erdogan united Antipodean politicians in outrage. This year’s ANZAC day events on April 25 will now need careful shepherding. As a result, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern warned a few days ago that the country’s Foreign Minister would travel to Turkey to confront Erdogan’s comments.

Some European conservatives have always opposed Turkey joining the EU. However, it is liberal theories of integration that are now being undermined by Erdogan’s cultivation of distinct Turkish communities in Europe. That raises a question of whether Mr Erdogan truly envisions Turkey inside the multi-ethnic and multi-religious EU.

Germany, Austria and the Netherlands have each attempted to minimise the extent to which Turkish political divisions are re-enacted on their streets by émigré communities. Banned from campaigning in Germany in 2018, Erdogan used his state visit to the UK to meet Mesut Ozil and Ilkay Gundogan, German professional footballers of Turkish origin.

The German authorities, who had worked hard to portray Ozil in particular as a successful example of integration, were aghast. Gundogan’s description of Erdogan as ‘my President’ made particularly uncomfortable reading.

Whilst Turkey’s spooks always kept a close eye on Kurdish and leftist exiles in Europe, Erdogan has used the General Directorate for Religious Affairs (Diyanet) to maintain religious orthodoxy among émigré communities, and to gather intelligence on rival Islamists. Last year, Austria closed seven mosques and announced that 60 Turkish-funded Imam’s were persona non grata.

More sinister examples abound. Following the curious botched coup of 2016, which Erdogan blamed on the West, Ankara has launched a wave of repression. Journalists and academics have been either jailed or barred from their professions, while Erdogan has even floated the idea that he might reinstate the death penalty. Only last year, 25 journalists were jailed for alleged links to US-based cleric Fethullah Gulen and thousands of academics have been dismissed from their jobs.

Turkish membership of NATO survived military coups in 1960 and 1980, and clear military diktat in 1971 and 1997. It is increasingly challenged however by Erdogan’s decisions. Despite past disagreements, Turkey is developing closer ties with Russia. In 2017, Erdogan signed an S-400 air defence deal with Putin worth $2.5 billion, causing national security concerns among US defence officials. As a result, Washington is considering halting the F-35 aircraft delivery to the Eskishekhir depot. According to retired General James Marks, Turkey is “raising red flags of NATO’s relevance in the region” and “there is a potential for Turkey to leave NATO by the end of the year”.

In its turn, Beijing is patiently waiting for Mr Erdogan to fulfil his earlier promise to “begin looking for new friends and allies”. China’s Belt and Road initiative incorporates many transit countries in Eurasia, including Turkey and Russia. China’s ambassador to Turkey, Deng Li, was recently quoted stating both Turkey and China were against protectionist policies, and that “both countries need an open world economy”. China hopes greater interdependence will reduce the possibility of conflict and rivalries, mitigating any risk to its ambitious global plans.

In moving closer to both Russia and China, Erdogan appears to be travelling in the opposite direction to the United States, the European Union, and NATO.

President Erdogan has set Turkey on a course towards religious nationalism, political opportunism, and an increasingly unpredictable foreign policy which undermines NATO’s strategic priorities. His comments on Christchurch, and the diplomatic breach they have caused, were not exceptional, but part of a wider pattern of behaviour emphasising the gap emerging between Turkey and the west.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.