In Andrey Tarkovsky’s only written work, the visionary Russian director recounts the letters he received from the public in response to his semi-autobiographical film Mirror. The content of the letters is varied and yet one theme recurs over and over again: “Everything that torments me, everything I have and that I long for, that makes me indignant, or sick, or suffocated me, everything that gives me feeling of light and warmth, and by which I live, I see it as if in a mirror”.

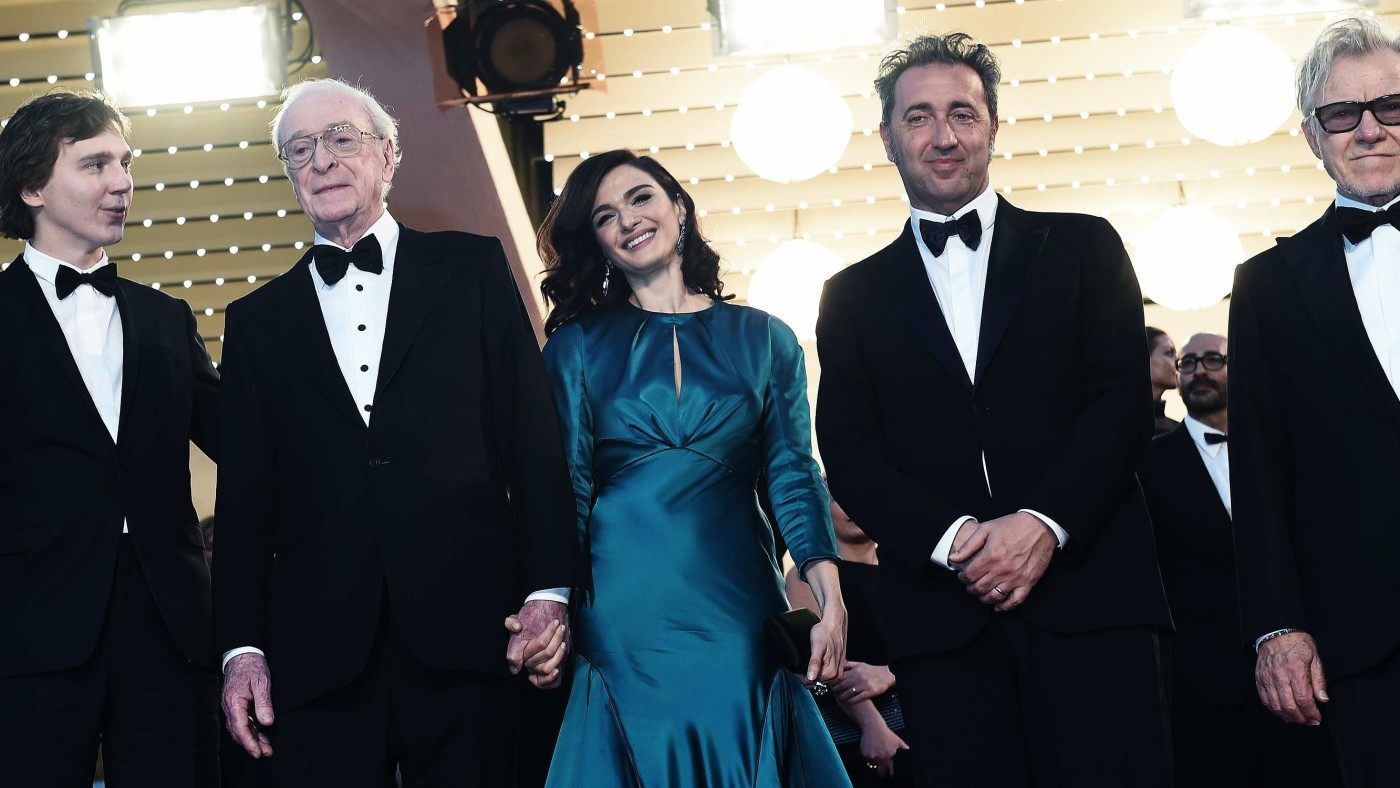

Paolo Sorrentino is the only living director who comes close to replicating the peculiar genius of Tarkovsky. His newest film, Youth, has just been released in the UK. It boasts an all-star cast including Michael Caine, Rachel Weisz, Harvey Keitel and Jane Fonda, not to mention an amusing cameo role for Paloma Faith. This is testament to the achievements of his earlier work. He is most well-known for The Great Beauty (La grande bellezza), released in 2013, in which Toni Servillo was cast as an ageing novelist who rediscovers writing after prolonged introspection.

Michael Caine plays a similar role in Youth: Fred Ballinger, a retired composer who returns at last to music. Caine’s performance is one of such brilliance that it is no surprise that Sorrentino created the film with Caine alone in mind. He combines wry humour and wit with a startling depth of feeling. The relationship between Ballinger and his daughter (Rachel Weisz) makes up one half of the work’s delicate fabric. The other is between Ballinger and his best friend Mick played by Harvey Keitel. The setting is a modern Swiss alpine resort, with its own odd sterility.

The film can be seen as a claim for the primacy of a particular kind of cinematic expression. Sorrentino foregoes traditional plot devices which rely on a realistic sequence of events. Rather, the film gains movement through the power of a singular image or sound. Dream sequences are interposed throughout. Scenes are laced with the sound of running water, the whistle of the wind in the grass, and the rustling of leaves. Dialogue is always framed within magnificent set piece shots. This owes much to the kind of cinematic language pioneered by Tarkovsky where the artificial divisions between audience, narrator, and characters are broken to be replaced by organic and natural imagery.

This concern with imagery over storyline makes for a sophisticated meditation on death, memory and love, and the answers that art can provide, or, more accurately, fails to provide. Sophisticated commentary is created by the film’s remarkable degree of self-reflexivity. Keitel plays a director who is also a retired actor. Jane Fonda appears as an actor playing an actor. Caine is an actor playing a musician. Sorrentino exploits these tensions to create a work of rich contradiction, ripe for diverse interpretation.

The film has its faults. The appearance of Adolf Hitler is a bizarre misstep. At times, it comes across as shallow. Sorrentino’s elaborate creation perhaps strays into self-indulgence at the moments where abstraction and detachment seem to replace intimacy. Even so, such moments are few and far between. Tarkovsky could make his public feel that his films were not just artificial representations of life, but life itself. We are privileged to have a director who will match, if not surpass the Russian’s achievement. Sorrentino’s work is far from finished and I hope that Youth, as significant as it is, will in the future be seen as a footnote to greater works.