I had plenty to be getting on with today, but Simon Jenkins’ latest Guardian column is so utterly, nonsensically wrong on housing and planning that I couldn’t resist fisking it.

Housing is such an important area of policy and it’s crucial we base our arguments on facts, rather than spurious assertions.

In the first two paragraphs alone there’s plenty to get stuck into.

Boris Johnson’s Queen’s speech was largely empty of substance. So thank goodness for the housing and planning secretary, Michael Gove. In his contribution he never spoke truer words, at least if anyone understood them. He has dismissed housing targets as “Procrustean … arbitrary … perfect arithmetic”.

In plain terms, what Gove meant was that Johnson’s mantra of “build, build, build” (a parroting of his chief party donors, the construction lobby) was senseless. The build-or-be-damned policies of David Cameron and George Osborne had funnelled jobs, people and money into the south-east of England, spawning characterless housing estates from Hampshire to East Anglia. This had enraged Tory voters in villages and small towns, because it sucked the life out of existing communities, crushing high streets and closing local pubs. The response at last week’s local elections was clear: stop the policy.

‘In his contribution’ is a weird way to describe a minister doing a broadcast round, but I’ll allow it.

‘What Gove meant was…’ – um, that’s not what he actually meant, or even what he said. His point was that there is no point building a set number of homes if they are shoddy, ugly and resented by local people – not that there’s no point in building homes. As for Boris Johnson’s ‘mantra’ of ‘build, build, build’, Jenkins presumably means the mantra the PM retreated from at his party conference speech in October, where he said that we should not be building on ‘green fields’.

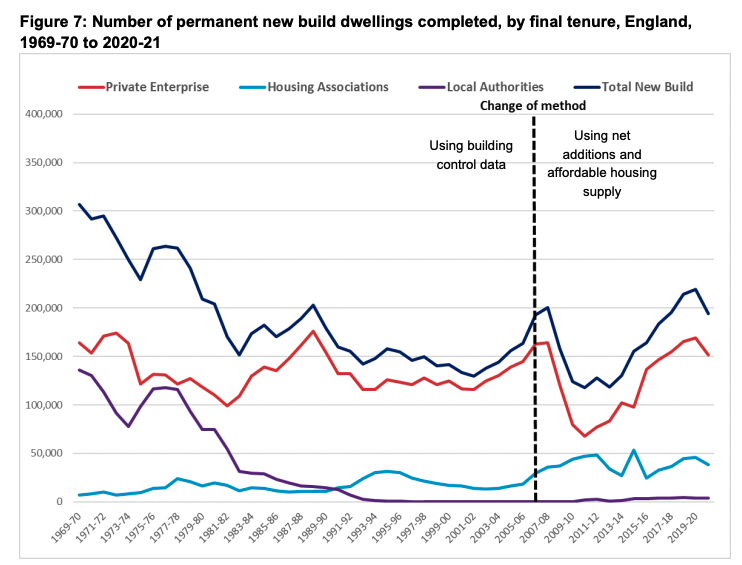

What about the ‘build or be damned policies of David Cameron and George Osborne’? Well, you can see the historic Coalition era surge in housebuilding in the graph below…oh wait.

.

As for ‘his chief party donors, the construction lobby’ – are they? This is the only thing I could find quickly on that, and it counts lots of people as ‘construction lobby’ who are basically just hedge fund guys, or make fitted kitchens.

The best bit is where he says Cameron allowed lots of building in the countryside, which people hated it because it ‘sucks the life out’ of villages and small towns. Rather than, say, providing people to use their shops and pubs and post offices?

I grew up in the countryside and can say with confidence that people who hate development do so not because they fear ‘sucking the life out’ of the area, but because they think it crowds the GP surgeries and roads (and ruins the views).

Not that we’re still only in the first two paragraphs here, which suggests housing activist Anya Martin was right to suggest this piece has more factual errors than sentences.

On we go, as Jenkins declares that the housing crisis is not, in fact ‘in crisis’ at all.

Sectors such as social housing are in trouble and need far more help. But property prices have been rising fast, up 11% from last year. They have risen in all rich countries, driven largely by decades of low interest rates.

First, the idea that an 11% rise in prices does not constitute a ‘crisis’ is very strange. Perhaps it’s not a crisis for well-heeled, home-owning newspaper columnists, but for the younger generation, it’s kind of an issue. Also, waiting lists for social housing historically rise and fall with market prices – and the wider market is where the crisis really is.

‘There is no Leninist requirement of a roof, bedroom and sitting room for each Briton, allocated by the state from birth to death,’ he continues, bizarrely. That might be true, but it doesn’t change the fact that people really want houses to live in and own. The ‘Leninist’ line is particularly odd because he then argues that we actually should allocate people one bedroom each. (On a side note, it is really impressive to write an article on the state of the housing market that doesn’t use the words ‘landlord’ or ‘buy-to-let’.)

The spare room fallacy

Now we come to a section about the number of spare bedrooms in the UK.

British housing – overwhelmingly in houses rather than the European preference for flats – is desperately inefficient. As the geographer Danny Dorling has noted, a third of British bedrooms are empty on any given night and even London has a bedroom surplus. Britons have 2.5 rooms each. As for new building, it has virtually no impact on price, since some 90% of house sales are of existing properties. Countries that build extravagantly, such as the US and Australia, have house prices soaring faster than Britain.

Do you know what might be causing this kind of misallocation, Simon? The fact that people can’t afford to buy those houses!

What’s more, the reason the UK seems to have a surplus of rooms is that homes in the UK are not only small, but tend to be divided into a large number of very small rooms. The number of rooms is therefore a very poor proxy for housing supply. As Kristian Niemietz points out, if more rooms actually meant more housing, we could double supply simply by putting a wall through every room. It is also a really well known fact among anyone who knows anything about the UK property market that we do not have an empty homes problem, compared to other countries – something Tom Forth has written about brilliantly here.

Also, yes, house prices are rising in Australia and the US. But they tend to rise, as in the UK, in the areas where people most want to live. Which tend to be the areas where it’s hardest to build. Supply and demand is, in fact, a thing. His claim that new building ‘has virtually no impact on price, since some 90% of house sales are of existing properties’ misses a really basic point about markets – that supply at the margins moves prices, often hugely. See, for example, the rise in grain prices since the invasion of Ukraine.

One of the few things Jenkins does get right is this passage on stamp duty:

If Gove really wants to bring down house prices, he should increase market flexibility. The most absurd tax in Britain is stamp duty, a tax on house transfer. Sales soared when the duty was suspended early in the pandemic, and have now slumped. Britons are reckless users of property. Stamp duty penalises downsizing and rewards housing waste. It is mad. The abolition of the tax would free up existing property, allowing retired people to swap places with young families. Higher council tax or a mansion tax would make more sense.

At last, something I agree with! The reason for the bedrooms problem is that it’s really expensive to downsize. Abolishing stamp duty would definitely help, and make the market more fluid. (Read this Centre for Policy Studies report for more on what an awful tax it is,)

But even in the midst of that, there’s that weird sentence ‘Britons are reckless users of property’. What? Do we treat our flats like dresses from Topshop or something? Just move in, wreck the joint and traipse off? I genuinely can’t work out what that sentence means.

Levelling down

Anyway, onward, to this passage on levelling up.

The biggest challenge for Gove is the other half of his brief. It lies in what he sees as the true nature of “levelling up”. Every prime minister since Margaret Thatcher has wanted to bless the north – or its voters – rather as the Victorians wanted to help the poor. Yet they all pumped infrastructure and housing subsidy into London, ever widening the gulf. Johnson often says levelling up does not mean “levelling down”. But he continues to tip vanity public spending into London, its railways, airports, bridges, sewers and even, it seems, the buildings of parliament. The reality is that if the north really is to be more attractive as a place to live and work than the south-east, then the south-east must be made less so.

He’s right that London and the south-east have had the biggest slice of the investment case. But ‘the south-east must be made less attractive as a place to live and work’ is…punchy.

Firstly, there are these things called productivity and cluster effects and tax revenues and public services. One of the country’s big productivity problems is that the best workers cannot get the best jobs, because they’re all surrounded by a cordon of unaffordable housing. Secondly, if ‘get on your bikes and look for work’ went down badly in the 1980s, ‘get in your car and look for houses’ is going to be equally unpopular. Thirdly, Jenkins appears to be arguing that it should be a literal aim of government policy to make a large area of the country a less pleasant place. As I said, punchy.

We’re into the closing stretches now.

This means putting a stop to first-time house-buyer subsidies for Londoners, which anyway just increase prices. For those on lower incomes, house prices would drop over time. It means, as previously mentioned, giving rich councils powers to set higher council tax bands to sting their wealthier residents, motivating them to downsize. It means making London less attractive to foreign property ownership and enforcing the subletting of vacant properties. The stark residential emptiness of the West End is so brazen it must explain the Tories’ loss of Westminster council this month.

There’s some acceptable stuff here: Help to Buy has indeed been a shambles. We’re way overdue a council tax revaluation. But ‘enforcing the subletting of vacant properties’? What happened to Leninist allocation being bad? It was only a few lines ago…

Also, ‘the stark residential emptiness of the West End must explain the loss of Westminster council’. Must it? Really?

Even on its own terms, this is wrong. If those properties are in fact empty, and were in fact rented out, would it really be to Tories? Or just to the type of people who tend to live in London, and vote Labour? So either we’re saying that the ordinary Tory-voting residents of Westminster were so affronted by empty housing that they voted Labour in (Partygate and the cost of living crisis they can take or leave – it’s the empty homes that gets them). Or that, er, something?

On to the penultimate paragraph:

Levelling up should mean not building over ever wider expanses of the south-east’s countryside to welcome northern migrants. It should mean increasing – and publicising – the competing attractions of the north’s countryside. What has appealed to London’s creativity has been the vitality of its Victorian market hubs and restored commercial architecture. The north has these in plenty and should exploit them. It should fight to keep its young skills, perhaps waiving student debts if graduates stay working five years in the north.

This all sounds very stirring, but these concepts don’t actually go together. Jenkins is saying we shouldn’t concrete over the south-east’s countryside, but we should in the north? How else would you ‘increase and publicise its competing attractions’? Send everyone a copy of All Creatures Great and Small?

Also, is the ‘vitality of its Victorian market hubs and restored commercial architecture’ really why people are in London? It’s an attraction – and by all means we should regenerate Northern cities too – but how do you fight to keep skilled people unless you, say, make sure they have homes they can afford? Something which he’s said throughout this column, incredibly weirdly, isn’t actually a problem (something something bedrooms something).

This does feel like part of the genre in which affluent southern writers conjure a vision of the North as a vast wilderness in which you can do all the grubby things like build houses for young people while leaving the view from your rectory pristine. Which of course ignores the fact that the North has green belts and Nimbys and housing pressures too.

Here’s the conclusion:

House prices are not a random variable. They reflect where people prefer to live. Britain’s poorer regions need policies to help them retain their talent, creativity and prosperity. This will be hard, but success will come when their house prices too can be “in crisis”.

Yes, house prices do indeed ‘reflect where people prefer to live’. So perhaps, just perhaps, we should build more homes for them in those places. Yes, there is definitely a case that monetary policy has played a huge role in driving rising house prices, but you can make that case without surrounding it with a filigree of contradictory nonsense.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.