It is no secret that Scotland, like many parts of the UK, faces deep-rooted social problems. And yet, despite being fetishised in films such as ‘Trainspotting’, these issues have been strangely absent in the independence debate.

The renewed calls for Scottish independence, like the old ones, are instead fuelled by nationalist sentiment and focus on the economics of severing ties with the rest of the UK – for this will bring great prosperity.

Yet prosperity is about far more than just wealth. Prosperity can be the product of free markets, good governance, and strong society, supported by vital indicators like high levels of wellbeing and good life expectancy.

It is not a purely economic measure, but a social one too. That’s why the case for sovereignty was made so powerfully during the Brexit campaign: it was how the UK would be able to be its best self and become more prosperous. If nationalism is not for this, what is it for?

So is true Scottish prosperity – both economic and social progress – best served by independence? The evidence suggests not for four main reasons.

First is the very simple fact that Scottish prosperity is below the UK average. Proponents of independence often like to compare Scotland to small, homogenous nations such as New Zealand or Norway. With New Zealand ranked 1st in the 2016 Legatum Prosperity Index™ and Norway 2nd, the assumption is that Scotland could too be top of the Index if only it were not constrained by the rest of the UK.

The UK Prosperity Index – measuring the same principles of the journey from poverty to prosperity – places Scotland as 10th of the 12 devolved nations and English regions. Scotland enjoys around 96 per cent of the UK’s average prosperity. Applied globally, this would put it at 18th, with the rest of the UK ranking 7th. Together, the United Kingdom currently ranks 10th.

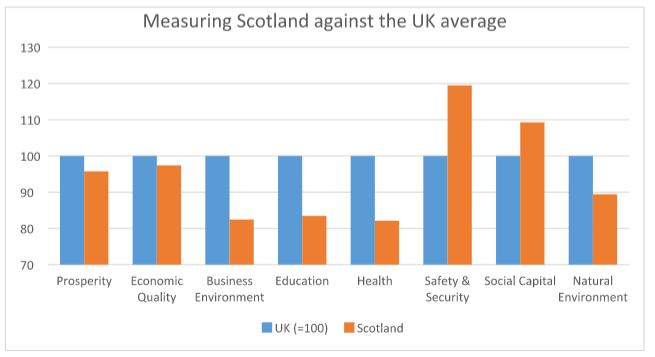

Second, Scotland’s prosperity deficit is concentrated in those areas that, to be a successful independent nation, it needs most to flourish: business, environment, health, and education. In these sectors the gap is more like 20 per cent (see graph). This has a significant impact on not only wealth creation, but the ability of Scotland to deliver the kind of social progress that is seen among the top ranked nations in the Index.

Caption: Comparing the Scottish average to the UK average across the Prosperity Index. Data taken from the UK Prosperity Index.

This isn’t Westminster’s fault. Both education and health are devolved issues – and the UK as a whole has the 5th best business environment in the world. An independent Scotland would rank outside the global top 30 for both business environment and education, and in the bottom half of the world in health.

Of course improvement is possible, but there are some significant hurdles to be cleared. Average life expectancy in Scotland is around 60 per cent of the UK average; cancer mortality is 17 per cent higher, and cardio-vascular mortality is a staggering 31 per cent higher than in the rest of the UK. This won’t change overnight.

Thirdly, these social problems have a massive impact on Scotland’s future economic prosperity. The economic challenges of independence have been well-rehearsed: dwindling North Sea oil revenues, a population that is ageing faster than anywhere else in the UK, the largest budget deficit in the OECD, and a significant debt burden.

Increasing productivity to offset the effects of high debt and ageing demographics is the ultimate answer to these challenges long-term. However, the weaknesses in Scotland’s wider prosperity make this an uphill battle.

With Scotland’s two high productivity sectors – oil and financial services – declining, raising productivity depends on Scotland’s capacity for innovation.

There is talk of tax cuts, but they would have to be significant to compete with the low corporate tax environments found elsewhere. They are also not the main driver of innovation, human capital is. Without a highly skilled workforce, innovative capacity is greatly reduced. Here, Scotland’s comparatively low health and education performance compared to the UK average presents significant challenges for Scottish prosperity.

Finally, comes the question of North Sea oil. The question of whether Scottish independence can be a success usually hinges on the size of the share of North Sea oil revenue received in a divorce with the UK. Let’s ignore the challenges of weak production and low oil prices; Scotland should be wary about relying on its natural resources to bring it prosperity.

The global Prosperity Index finds no relationship between prosperity and resource rents as a percentage of GDP, regardless of how you cut the data. There is not an automatic prosperity dividend to be had, regardless of whether Scotland secured 9 per cent or 90 per cent of North Sea revenue. Prosperity cannot be mined, it has to be consciously fought for.

The UK has made its decision. It chose to leave a union in which average prosperity is lower in every single area compared to the UK. The median EU prosperity rank is 30th. The UK ranks 10th, with the best business environment in the EU and the third best education system.

Scotland, too, could choose to exit its union. However, it would be leaving one in which it is a less prosperous partner and is disadvantaged in some of the most important foundations of prosperity. If a flourishing country is the aim, then it is one best served by the nationalists fighting to protect the Union.

An independent Scotland may succeed. Brexit Britain may flounder. We cannot predict the future. However, we can say with confidence that Scotland’s path to prosperity would be far harder to travel alone. If sovereignty calls, then we should not stand in Scotland’s way. However, Scots must understand that going it alone would make their future even more uncertain.

Prosperity in an independent Scotland: Analysis from the Legatum Prosperity Index