The origin

It all started with a Big Bang on 27 October 1986.

The overnight deregulation of the financial sector, including the abolition of fixed commission charges, and the move from open-outcry to electronic screen-based trading, pushed London to become the most important financial centre in the world and drove the global economy relentlessly forward.

A vision of the future

The following year, Tom Wolfe caught the spirit of the age in Bonfire of the Vanities. His phrase “Masters of the Universe” describes the new breed of aggressive and technologically-enhanced bankers whose mega deals forced stock markets from one dizzying height to the next. Wolfe’s book depicts a dystopian world in which bankers’ rampant greed and ambition facilitated by electronic trading and lax regulation blinds them to – and isolates them from – the lives of regular people. Presciently, he outlines a world in which public confidence in the social benefit of the financial system has been replaced by suspicion, scepticism, resentment and distrust.

Two decades of unprecedented growth

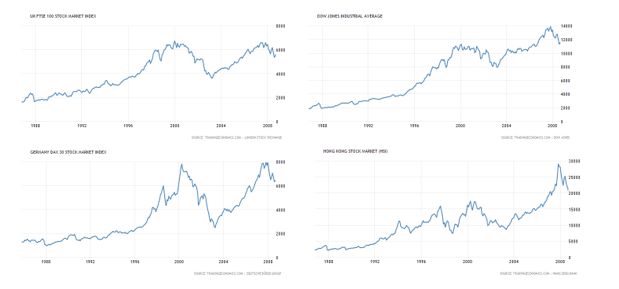

Back in the real world, banks and bankers generated enormous wealth for two decades. There were dips, particularly the pricking of the “dot-com bubble” in the early noughties, but the FTSE and most other international markets trebled – or more – in size between 1986 and 2008.

By the late 1990s the growth was so strong and sustained that the Chancellor, Gordon Brown, regularly claimed that his government had established “a new economic framework [that secured] long-term economic stability and put an end to the damaging cycle of boom and bust”.

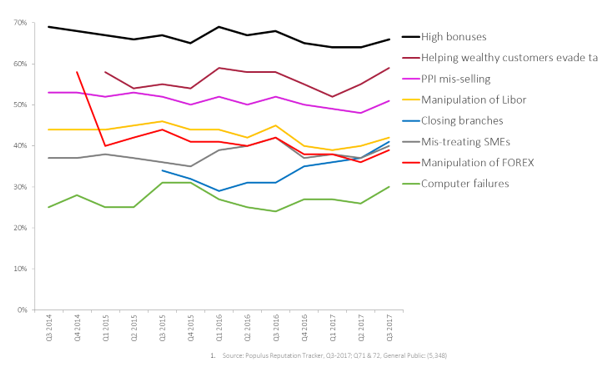

However, this period of economic stability was fuelled by bankers taking advantage of increasingly complex financial instruments which few understood, including banking regulators around the world. Emboldened by a lax regulatory regime, some bankers used illegal and immoral activities to maximise profits including manipulating Libor and FOREX markets, mis-selling protection payment insurance (PPI), helping wealthy customers to avoid tax and the securitisation of sub-prime mortgages.

The party’s over

In September 2008, the party ended with the collapse of Lehman Brothers which brought the world’s financial system to its knees. For two weeks bankers, regulators, politicians, journalists and the wider public were frozen, heads in their hands, waiting for a saviour.

An unlikely saviour

On 8 October 2008 Chancellor, Alistair Darling, unveiled a £500bn rescue package for British banks and bailed out Lloyds and RBS with taxpayers’ money. The rescue, via Quantitative Easing (QE), became the template for governments across the world and was praised by economists including Paul Krugman the Nobel Prize winner for Economics: “Mr Brown and Mr Darling have defined the character of the worldwide rescue effort, with other wealthy nations playing catch-up…. Luckily for the world economy … Gordon Brown and his officials are making sense…. They may have shown us the way through this crisis.”

Quantitative Easing

In short, QE is printing money, not in a physical sense, but digitally, in the form of government-backed IOUs. This flood of debt was designed to lower interest rates artificially, keep markets liquid and spur the economy. It had never been tried before and no one knew whether it would work or not.

It did work – sort of. Cheap money encouraged banks and insurance companies to borrow and re-invest, in turn businesses and consumers had access to cheaper credit and they borrowed more and re-invested more. In theory, government-backed credit should slosh through the economy as it is lent and re-lent, trickling down and lifting all boats. But, in practice, QE doesn’t trickle down equally.

The biggest beneficiaries of the more than $8tn of QE released by central banks over the last decade have been the asset-rich including banks, insurers, asset managers, hedge funds and property holders. On the other hand, for those with few assets, particularly lower socio-economic groups and the young, QE has been characterised by job insecurity, rising house prices, sluggish real wages and widening inequality.

The long hangover begins

Despite this tsunami of cash, the world went into the greatest recession since the Great Depression. Aftershocks, such as the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone and a slowing Chinese economy, continue to shake the global economy.

It is true that QE saved us from a far worse fate. Most economists would support the bank of England’s assessment that without QE, “most people would have been worse off. Economic growth would have been lower. Unemployment would have been higher. Many more companies would have gone out of business. This would have had a significant detrimental impact on savers and pensioners, along with every group in our society.”

Cure turns to crutch

However, according to its architect, Alastair Darling, QE was meant as a “short-term shock therapy, not a long-term remedy for a chronic problem”. A decade on from the collapse of Lehman Brothers and only the US has committed to a programme of winding down QE and bringing interest rates up from their historically low base. Economies around the world have become hooked on cheap credit provided by QE.

According to the International Monetary Fund, global debt has increased by nearly 50 per cent to $225tn in the decade since the collapse of Lehman Brothers. As Alberto Gallo says, “Businesses and homeowners became dependent on cheap credit and the asset bubbles created mean you get caught in a kind of ‘QE infinity’ trap: you can’t turn off cheap credit without fundamentally shocking the financial system, so you prolong it instead. An addiction to cheap credit is a fundamental flaw in our economic system.”

While politicians delay, the misallocation of resources continues with the asset-rich benefiting at the expense of the asset-poor and the generational divide widens with Baby Boomers benefiting at the expense of Millennials. As inequality between those with assets and those without grows, so does the potential for populism. The election of Donald Trump, the Brexit vote and the rise of the right across Europe can, at least in part, be attributed to the collateral effects of QE.

Where does this leave banks and bankers?

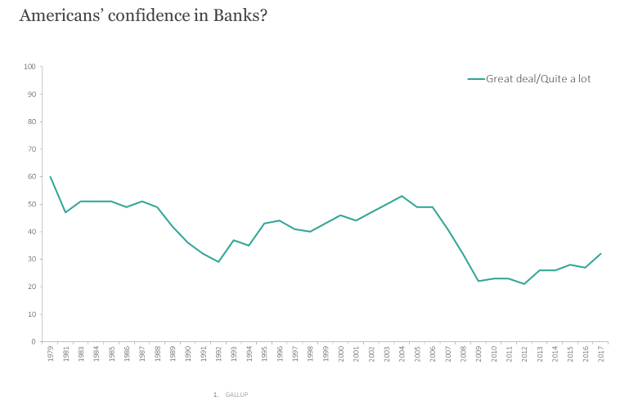

Trust in banks and bankers has crashed. The Masters of the Universe have been shown for what they are – the same as the man behind the curtain in the Wizard of Oz.

We live in the world that Tom Wolfe foresaw in Bonfire of the Vanities. A world in which public confidence in the social benefit of the financial system has been replaced by suspicion, scepticism, resentment and distrust. According to Gallup, Americans’ confidence in banks and bankers plummeted with the financial crisis in 2008 and has hardly recovered at all in the last decade.

In short, most people think that banks behaved recklessly, took their money in the biggest corporate bailout in history and acted in their own interests at the expense of their customers. Many believe that banks got away with it, because nothing appears to have changed: no bankers (or to be more accurate, very few) have gone to prison, they still get bonuses that are hundreds of times bigger than the average annual wage and consumers are still suffering from a global economy that has been holed-below-the-waterline by banking misconduct.

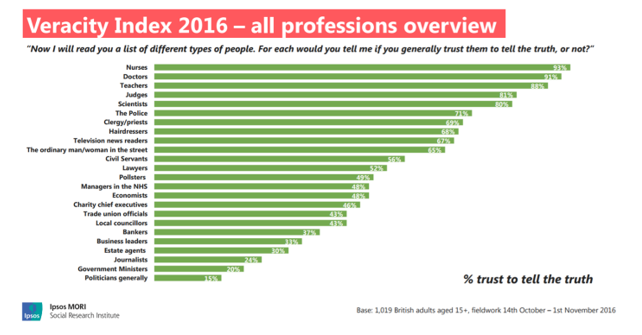

In the eyes of the public, banks have done little or nothing to persuade them that they have changed. Less than half of the UK population trust any bank to do the right thing. Attitudes toward British banks have been damaged by high bonuses, tax evasion, PPI mis-selling, manipulation of Libor and FOREX, mis-treating SMEs and IT failures.

What has damaged my view of British banks?

In the “post-truth” age, in which disgruntled populations reject expert evidence in favour of gut-instinct driven by mistrust of political, business and even scientific elites, banks face an even more challenging environment. Mistrust is ossifying and it is becoming harder to convince an increasingly sceptical public that banks play a positive role in their customers’ lives and communities.

Banks, which have spent much of the last decade painfully rebuilding balance sheets, conforming to stringent regulation, paying eye-watering fines for the failures of previous management teams and working hard to return to profit, find it difficult to accept that they have not changed. They protest that the banking system is much safer and more secure now than it has ever been and want some credit for helping to turnaround the economy.

There are lessons for the banks though.

Just because it hurts internally, doesn’t mean that it’s working externally.

Over the past 10 years, banks have experienced big painful changes. They have cleared out Boardrooms, slashed workforces, endured punitive fines, taxes and regulation, rebuilt balance sheets, returned to profit and helped the global economy to grow again – but no one cares. To the wider population, these activities are the least that the banking community should be doing and many don’t believe that banks would have been brought to heel without legislative intervention forcing them to behave better.

Trust in technology isn’t the problem; it’s trust in your intentions that needs to be addressed

For banks, the trust problem has focused on getting customers to trust new technology like online banking apps to make banking faster, more efficient and less prone to fraud. This drive to online is aligned with customer demand and social trends. It underpins the rationale for dismantling expensive branch networks which are becoming less and less relevant to modern banking.

But, this is missing the point. It is not that consumers don’t trust technology (though this is somewhat true). Their mistrust is deeper and more fundamental. They don’t trust banks to tell the truth. They don’t trust banks to put their customers’ interests ahead of the interests of the bank.

To improve trust, banks needs to manage the move from “bricks and mortar” to online better. Most people get that the direction of travel is towards online, and banks should be monitoring the attitudes of young people carefully to understand the needs of modern customers, but too many people feel that they are being left behind. Banks needs to demonstrate how they are catering for the “left behind” consumer – particularly the older generation who can’t or won’t move online.

Banks are currently seen as a functional necessity, but don’t have an emotional connection with consumers. They are functional utilities, trusted to hold money safely and transfer it accurately – and that’s about it. They are not trusted to act in the best interest of their customers. No one changes banks, because none is seen as substantially better than the other – they all do the same thing in much the same way. What’s the point of changing bank when you don’t trust any bank to put your interests as a customer above its own interests?

Regain the lost emotional link with consumers

The successful banks of the future will be the ones that regain the lost emotional link with consumers. It’s at the heart of complaints from older customers who want to go back to the days when the bank manager knew their name. And young people who want an injection of humanity too, in a different way (they are often networked electronically at a superficial level, but are crying out for personal contact). What both really want is personalised and targeted products that recognise them as individuals and help them to achieve their goals. They want a bank that sees them as a person rather than an account.

Counterintuitively, AI technology is possibly the best route to achieving this personal and expert connection. There is a long way to go. According to global research by HSBC only 19 per cent of the population would trust a robo-advisor to help them make choices around investments, with trust falling to less than 10 per cent in many developed countries. However, AI advisors could address a fundamental issue for banks: how can they treat each customer (rather than just the wealthiest) with relevant, personal and expert advice at scale and at a viable cost? An army of AI consultants which can access more up-to-date lending and investment information than their human counterparts and which can be programmed (with independent verification) to place the interests of the customer ahead of the interests of the bank, might be a feasible way of re-connecting with everyday customers.

To regain trust banks need to demonstrate how AI advisors will benefit and personalise the experience of customers. They need to explain how digital advisors will be able to harness the wisdom of multiple experts at a low cost and whenever it is convenient to customers. They need to show how robo-consultants can be updated with real time information, examine a range of market options, work together with humans and adapt and personalise advice in real time.

Obviously, social change is required for this to work, but it is already starting, just look at how quickly Amazon’s Alexa is being taken up by consumers. Ironically, the pathway for banks to re-establish trust by rebuilding a personal and emotional connection with customers may come via robo-advisors, rather than real people.

If banks don’t rise to the personalisation challenge, there are others who will. The Amazons and Googles of this world already hold vast reserves of personal data and use AI to leverage trusted relationships with users. They are well-positioned to replace banks as volume providers of financial services. Right now, it’s not the fin-tech start-ups that are poised to eat the banks’ lunch, it’s the tech giants.