Viewed from almost any angle, the UK government’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme — to give the furlough policy its official title — is a staggering departure in the state’s relationship with the economy. Not since the foundation of the welfare state in 1948 has a British government intervened so emphatically to ameliorate labour market outcomes. And even then not to subsidise employees’ wages directly, as now.

The policy’s vast scale is a story best told in numbers. According to HMRC data, at least 9.6 million jobs were furloughed at some point – more than a quarter of the UK’s entire labour market. This level of support, rather unsurprisingly, does not come cheap. By the time the policy is wound down in October, the scheme’s cost could exceed £40bn. With the economy in freefall, there is only one way the government can fund this: borrowing. As such, the UK’s public deficit is expected to reach 19% of GDP, a level not seen before in peacetime. Total public debt is bigger than the economy for the first time since 1963.

Whether such largesse will prove well spent depends on what comes next. For while the scheme has undoubtedly saved countless jobs so far, if it fails to nurture the economy through to a softer landing, with manageable levels of unemployment, searching questions will be asked abouts its value. As labour market expert Paul Gregg puts it, the key variable is how threatened firms feel about potential bankruptcy – that is when the axe really begins to swing. Indeed, part of the subtle genius of furlough’s design was to grasp this insight immediately and provide a safety net for workers that also doubled as a business resilience policy. However, this connection to businesses’ ‘animal spirits’ is also a threat if support is removed before confidence fully returns. The million-jobs question therefore, is whether the government’s current timetable to end the scheme in October will salve the future fears of business leaders at the sharp end of the economic crisis. If not, then furlough will prove a job half-done, leaving us with a hefty bill and limited benefit.

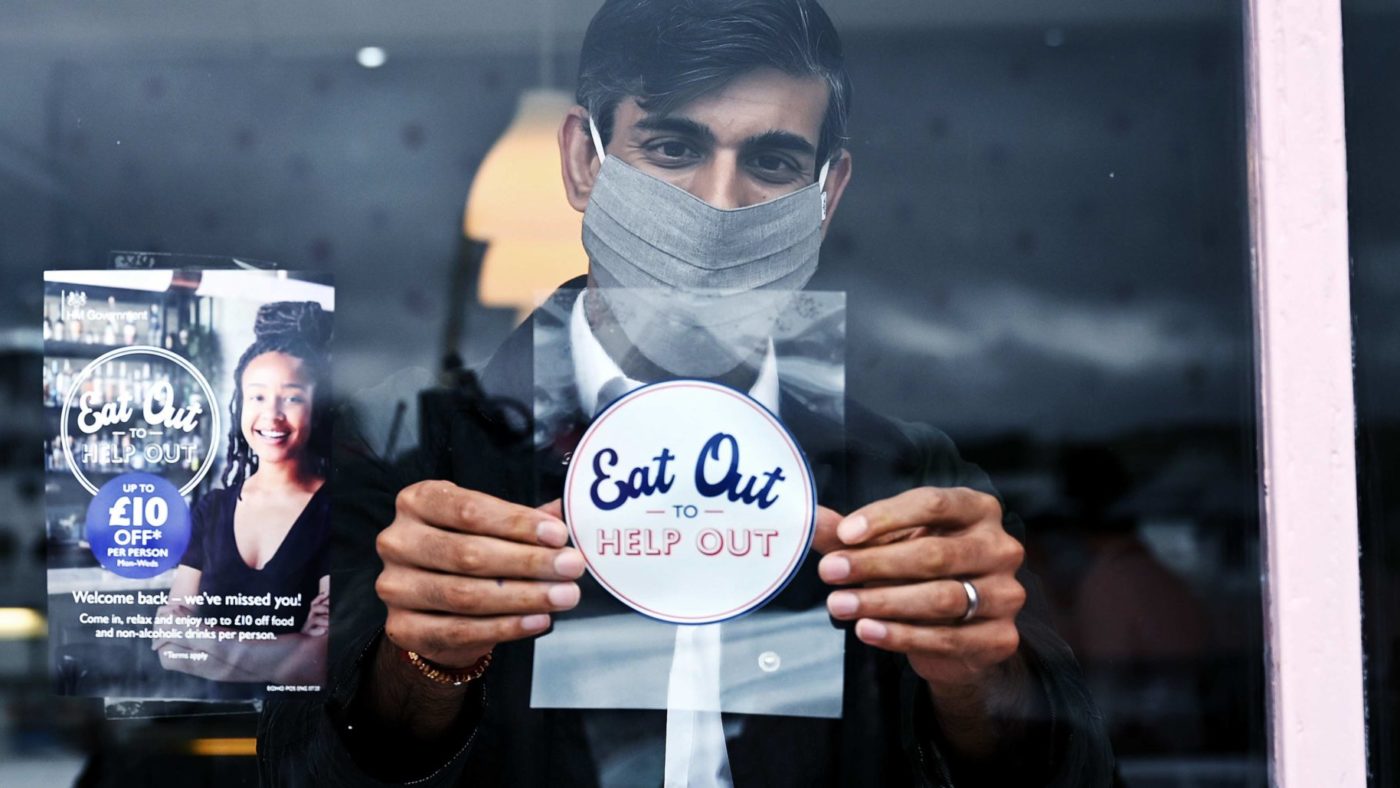

These are the scales Chancellor Rishi Sunak must weigh as he approaches his third budget of this extraordinary year. Perhaps uniquely in Whitehall, he and the Treasury have had a good crisis. Notwithstanding some operational difficulties with the self-employed income support scheme, his rapidly constructed safety net, with furlough at its heart, has held up well. Meanwhile, his “eat out to help out” restaurant subsidy – which, full disclosure, I mocked on announcement – appears to have substantially transformed consumer behaviour in a way that will surely have a recovery-boosting spillover effect.

Yet it is this autumn’s momentous decisions on the future of furlough, with all the consequences for employment, that will likely define medium-term perceptions about both his and the Government’s handling of the entire pandemic. And this is where things start to get tricky. For the further we move away from lockdown, the more the economic effects of the pandemic will be heavily targeted on particular sectors, workers and communities. In fact, the furlough data itself tells a story of an economy where different sectors are adapting to the so-called ‘new normal’ at a varying pace. For example, RSA analysis of ONS survey data shows that 60% of furloughed workers in the “accommodation and food services” sector – hospitality and tourism – have now returned to work, a much higher percentage than in sectors like the arts (29%) or administration (28%). Then there is the small matter of local lockdowns – as it stands, the safety net which supported the country through the spring will not be available to towns and cities shut down beyond October.

There are all sorts of policies that might respond to these challenges creatively. But policy imagination is not the Treasury’s weakest suit – both the furlough and “eat out to help out” schemes are a testament to that. What it finds more difficult is working with other sources of political authority as equal partners in policy delivery and design. This is structural as well as cultural, striking to the heart of Britain’s over-centralised but underpowered state. For example, if the Chancellor wants to distribute a particular policy only to workers in a particular sector – or even a particular sector in a particular area – to whom does he turn to deliver that?

At the start of the crisis, I urged the Chancellor to turn to Britain’s local authorities and trade unions on this – they remain his best bet. But either way, as the nature of the pandemic becomes more localised, his furlough scheme must adapt. This will require him to embody a more open, flexible and decentralised style of leadership than the bunker mentality espoused by his next door neighbours. Which is a contrast, one suspects, he might consider politically intriguing.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.