In May 2017, champagne corks will be popping in London as the first branch of Crossrail comes into operation, running between Liverpool St and Shenfield. When the new service – renamed the Elizabeth Line – comes into full operation, it will be the culmination of Europe’s largest construction project, a multi-billion-pound symbol of London’s status as a global city and a global leader.

Except that it isn’t Europe’s largest construction project at all.

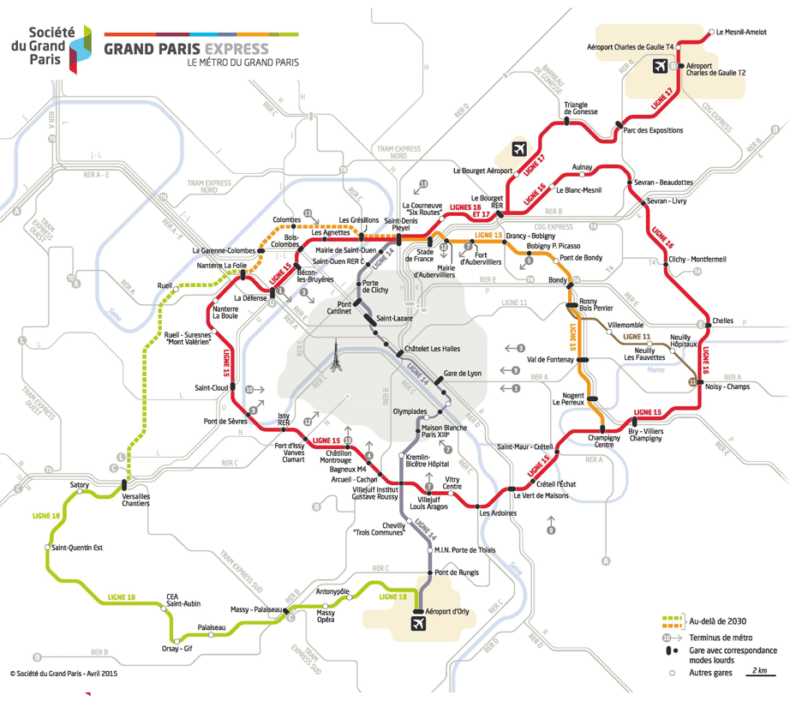

Over on the other side of the Channel, the city of Paris is embarking on a transport project to put Crossrail to shame. You Brits had 100km of track? We will have 200. You invested 17 billion euros, and built 10 new stations? We will spend 32 billion, and build 68. You are linking up with Heathrow? We are linking up with all three of our international airports. You are carrying half a million passengers a day? We will carry two million.

Get more from CapX

Follow us on Twitter

Like us on Facebook

Sign up to our email bulletin

The Grand Paris Express, as this project is known, is in part a solution to a very French problem. The city of Paris has extremely good transport links – if, that is, you want to travel into or out of the centre. If you actually want to move around outside the central arrondissements, you’re screwed.

This is mirrored in the city’s geography. All the best jobs and all the best houses are clustered in the centre. The urban poor are largely parked in the banlieues – most notoriously in the cités, the giant concrete housing projects that have become a breeding ground for deprivation and radicalisation. They are cut off from prosperity not just economically, but physically.

The Grand Paris Express is meant to change this. Consisting of four separate lines, which will be completed between 2019 and 2030, it will encircle the traditional city centre, connecting the two million people inside it with the 10 million outside – indeed, of the 68 new stations, more than 30 will service the most deprived areas.

Yet the broader idea of “Grand Paris” is about something much bigger than just transport connections. It is, say its supporters, the biggest transformation of Paris since Baron Haussmann. And the goal, to put it bluntly, is to knock London off its perch.

Paris is, according to Catherine Barbé, director of strategic partnerships for the Société du Grand Paris, the umbrella body overseeing the project, “the engine of the French economy”. All told it has 30 per cent of French GDP, the largest amount of office space of any city in Europe, more of the world’s biggest companies than anywhere except Beijing and Tokyo, and more people working in R&D than any other region in Europe.

When the Grand Paris plan was launched by Nicolas Sarkozy in 2008 – complete with the creation of a dedicated Cabinet-level post to oversee the project – the explicit goal was for the newly expanded Paris, as the marketing materials say, to “take its rightful place in competition with the major global cities”.

While the railway itself will be publicly funded, via a combination of borrowing and a levy on households and businesses, the idea is to turn the hubs of the new transport network – the points at which the various lines meets – into clusters of innovation and investment. It is the same strategy which London has successfully adopted: hence the skyscrapers sprouting up near King’s Cross, Paddington and Victoria.

“By 2030, Grand Paris will be far and away the largest European city in terms of number of companies,” says Xavier Lépine, President of the French investment giant La Française. “In every economic sector we have a world leader – L’Oréal, Total, BNP, Michelin.”

Over next 15 years, combined investment from the public and private sector is expected to total around 100 billion euros – or 5 per cent of GDP. Paris’s prospect as a risk-free investment opportunity are, Lépine says, especially attractive to Chinese investors.

The result is a project that is at once top-down and bottom-up, entrepreneurial and dirigiste.

After all, Paris is attempting to make itself Europe’s best place to do business not via a series of structural economic reforms, but by the grandest of grand projets.

The goal may be to rival – or topple – London, but the inspiration is as much the sweeping urban development of a Beijing or Shanghai as something like Crossrail: indeed, the Chinese capital is incorporating and redeveloping its hinterland in precisely the same fashion as Paris.

And unlike London, which has shaped itself around financial services, Paris will be seeking to lead the continent on all fronts. The 10 hubs proposed include Croissant Ouest for media and start-ups. Villejuif-les-Ardoines for life sciences. Noisy-Champs/Marne-la-Vallée for sustainable development. Le Bourget for aerospace.

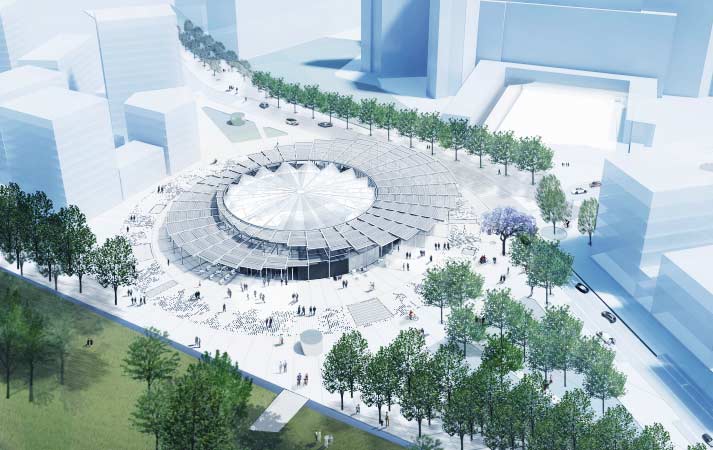

Each of these projects will be on a grand scale. At St Denis-Pleyel, where four of the lines meet, “we expect as many travellers as there are at the new World Trade Center station in Manhattan”, says Barbé. The potential of this “creative/design cluster”, which boasts 7.6 million sq ft of new office space, is enormous – “It’s another Docklands”, she insists.

Villejuif, by contrast, is already home to the Institut Gustave Roussy, arguably Europe’s leading cancer research centre. The problem is that it’s in the middle of nowhere.

Under the Grand Paris Express plan, Villejuif will get its own station on the direct line to Orly airport – with extra space for pharma firms. More fundamental research will be handled by the university at Saclay in the south-west: the aim is to increase its contribution to France’s research output from 10 per cent to 20 per cent, with the energy giant EDF building a giant research centre.

And then, of course, there is financial services.

Europe already has a financial capital. But on La Française’s presentation to investors on the relative merits of Europe’s leading cities, the phrase “Brexit = risk” is picked out in the London section in bright red letters.

And one of the key clusters in the Grand Paris project is the existing financial centre at La Defense – which has plenty of spare real estate in the shape of the former train yards to its west.

“Three major cities are active in managing money – New York, London, Paris,” M Lépine explains. If banks and traders flee Britain after Brexit, he says, Amsterdam and Dublin are too small – and while Frankfurt has the larger stock exchange, it does not have the same number of large banks and insurance companies as its French rivals. Paris, however, “has all the technologies and all the people”.

“The thing to look at is not where people are listed, but where there are the investors and opportunities,” he adds. “If someone has to leave London, they will choose a city with enough space – space for schools, space for families, space for their quality of life. We have the financial diversification, the transport infrastructure, and the social infrastructure as well.”

For Lépine, the chance to steal the City’s lunch is an obvious outgrowth of the project: “The City will not disappear after Brexit. But Paris certainly has some potential to take a part of its business.”

Yet building up Paris’s financial sector is, for him, just part of the wider plan to make it Europe’s leading city.

“In the 19th century, Paris was the capital of the world,” he says. “The capital of finance, theatre, industry.” But in the 20th century, “Paris was just not there”.

“It’s always been sad for people like me to see that Paris – most of it – is not a success,” he adds. Which is why, for him, the chance to contribute to arguably France’s biggest project of the 21st century is like a dream come true.

“People here took 20 years to understand what we don’t do well,” he says. But now they accept that “there is no alternative”.

Yet despite the obvious economic logic, he admits that he “never imagined” that a project on this scale could be attempted: “I’m like a child in front of the largest chocolate cake ever.”

Elsewhere on CapX

Meet the man bringing Thatcher to France

Why London can cope with Brexit

How the world conquered the City

For Barbé, too, the Grand Paris project is proof that “the town of Paris has come back after a century of being overshadowed by New York, and more recently by London”.

In an age when the great cities are the great engines of prosperity – the great accelerators of wealth and innovation – Britain has been blessed by London’s unique position of European pre-eminence.

It is far too soon to tell whether the Grand Paris project will live up to its backers’ hopes. But it is certainly the case that Britain’s capital could soon have a fight on its hands.