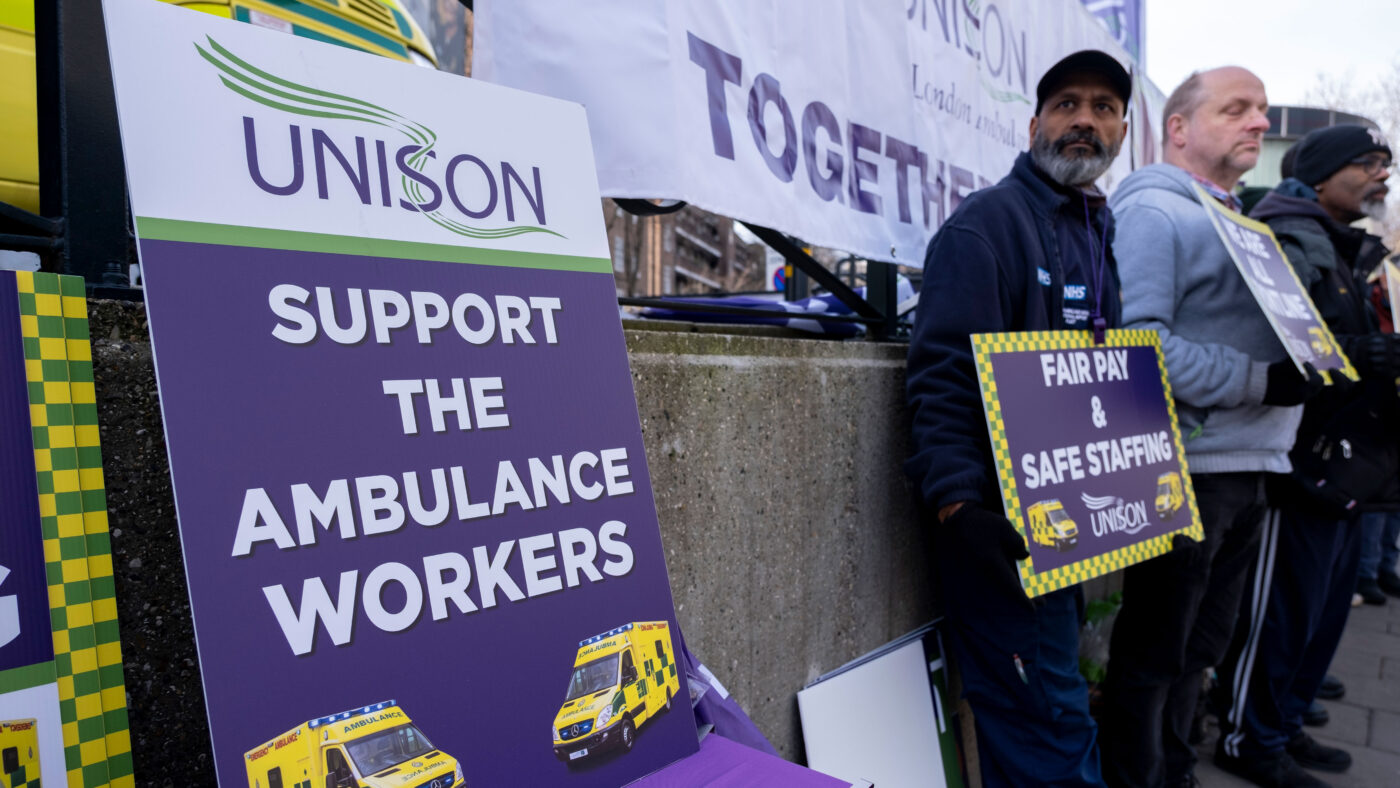

Left-leaning politicians and trade union leaders from around the world have signed a statement denouncing the Strikes (Minimum Service) Bill currently making its way through the House of Lords.

The last Conservative manifesto promised legislation to impose a minimum level of service during railway strikes, which on certain parts of the network were already endemic before the post-lockdown national stoppages which we have seen since the middle of last year. Given the recent rash of strikes across the public sector, the legislation in the Westminster cooking-pot now goes beyond the original proposal. It covers other transport services, health services, fire and rescue services, decommissioning of nuclear installations and management of radioactive waste and spent fuel, and border security.

The bill empowers the relevant Secretary of State, following consultations with interested parties including relevant unions, to issue a ‘work notice’ identifying individuals required to work during a strike to enable minimum levels of provision, and specifies the work that is required.

The statement signed by over 120 politicians and unionists from 18 countries seeks to present this procedure as a fundamental attack on the right to strike. In launching it, TUC General Secretary Paul Nowak argues that the UK ‘already has some of the most restrictive anti-union legislation in Europe’ and that the bill ‘will only drag the UK further away from democratic norms’.

Nowak goes on to say that the Bill is ‘almost certainly illegal’, a curious thing to say about a bill which is going through our still more or less sovereign Parliament. I suppose he has in mind the idea that, as the UK is signed up to the ILO’s declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, the courts might find against the Government in a test case.

Little about our legal chums surprises me these days, but I doubt this one has legs. As a CPS paper by Nicholas Finney pointed out some time back, the TUC used the same argument against the requirement in the Trade Union Act 2016 for strike ballots in important public services – broadly the same services as those listed in the new Bill – to meet a threshold of 40% of eligible members to vote in favour of strike action. But the ILO refused to swallow the argument then, and I doubt they will in this case. They recognise that there are some legitimate restrictions on the right to strike.

To be pedantic, this ‘right’ does not exist in Britain in the way it does in continental legal systems, which often seem to need a ‘right’ to be defined before you can blow your nose. In common law set-ups such as we have historically enjoyed, you are perfectly free to strike. However, as this involves a breach of an employment contract – just as would disruption to any other contract – it is potentially actionable at law. Thus trade unions have been given ‘immunities’ from criminal (since 1871) or civil (since 1906) sanctions for strike action. These immunities have always been subject to certain conditions being met, including (since Mrs Thatcher’s day) properly conducted secret ballots.

In any case, there are clear examples of similar legislation on minimum service provision in a number of European countries – Spain, France and Italy are frequently mentioned – so we are nothing like the anti-union pariah that the TUC disingenuously claims.

In fact, many continental jurisdictions ban strikes outright in key sectors. For example in Germany civil servants (including university staff and many schoolteachers) are prohibited from strike action. So are some categories of Danish civil servants; the same is true in Czechia and Slovakia, where fire and rescue workers, air traffic controllers, health workers and various other miscellaneous categories are also banned from striking.

So it’s perfectly reasonable for our Government to press ahead with minimum service agreements if it thinks they will help. My concern, as I’ve previously argued on CapX is that these agreements will probably have little effect. It will likely take an age to set out detailed requirements, and then we will probably find the outcome in service terms will differ little from previous voluntary arrangements.

Would that matter? After all we have plenty of ineffective laws which are intended mainly to make a political point or impress particularly dozy electors. It all depends on whether the current round of strikes will blow over or is going to herald a prolonged period of 1970s-style industrial action. If the latter, we should probably forget this sticking-plaster approach and instead go for radical surgery: breaking up state monoliths such as the NHS and our education system to recreate a genuinely competitive labour market where possible, and imposing outright bans and/or compulsory arbitration in areas of irreducible state responsibility.

We seem to accept quite happily that the police and the armed forces can’t strike. How are they really any different from workers in, say, the fire service, border controls or A&E? They ought to be paid reasonably and treated fairly, with properly constituted pay reviews, but not allowed to put the public at risk or indefinitely extended inconvenience in order to screw a marginally better pay settlement out of the taxpayer, or resist organisational change which would boost productivity and economic growth.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.