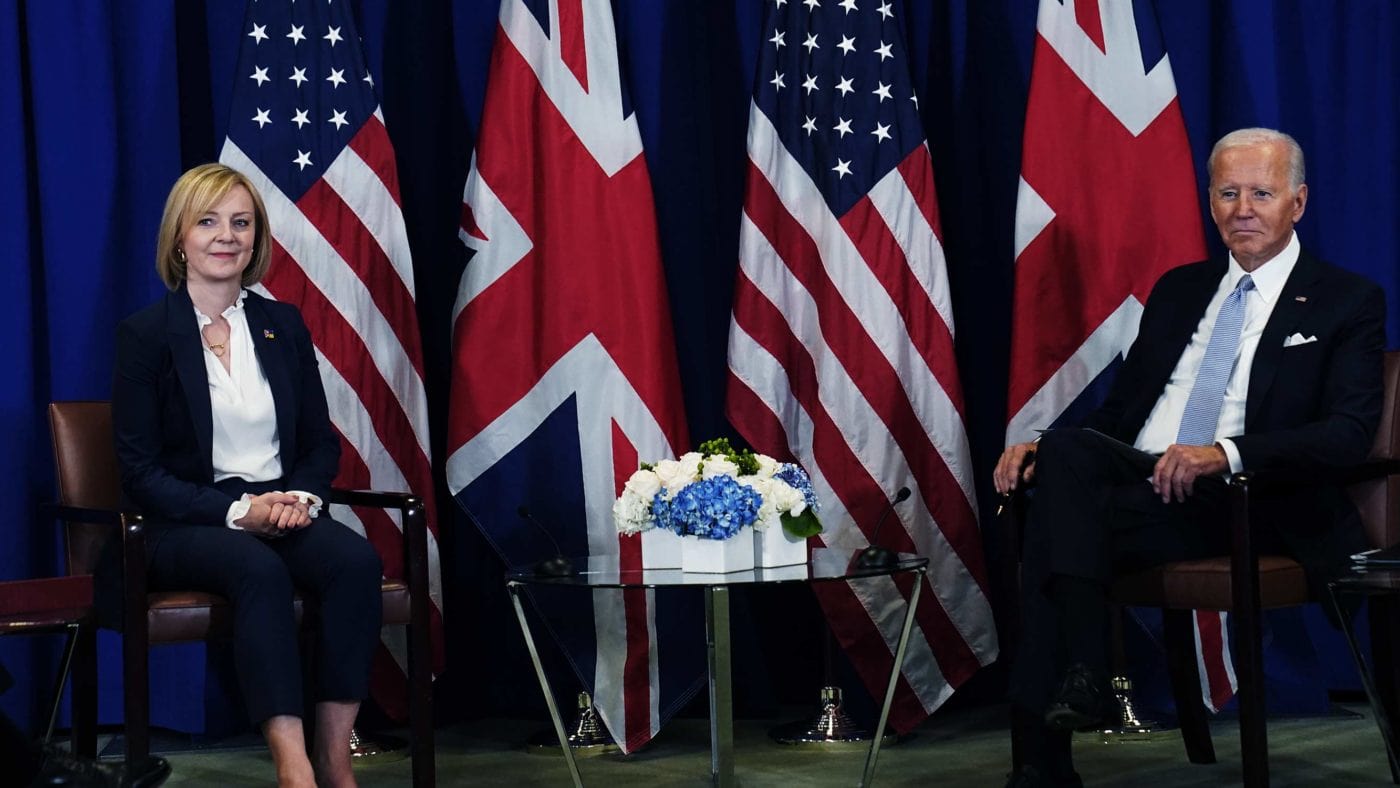

It’s easy to lose track of world events these days, especially if you’re on a tracker mortgage. However, not enough has been made of Liz Truss’ visit to the United States last week and the question of our much vaunted ‘special relationship’.

I’m not well qualified to speak about a post-Brexit trading partnership with the States, except to say that any attempt to reset it seems overly contingent on how sentimental ‘Irish Joe’ is feeling on any given day about the auld country. That’s probably one of the reasons the Government has all but given up on a trade deal, at least for the foreseeable future.

Of more immediate concern is Biden’s seemingly limited understanding of the harm a fully implemented Northern Ireland Protocol would do to the Belfast Agreement that he supposedly reveres. ‘Protecting’ an interpretation of that peace deal that reads like a contingency plan for a united Ireland might play well in Boston bars, but it doesn’t hold much sway in Loyalist estates where a collapse in community morale – aggravated by recent demographic news – presages a return to a dark past.

Important though the Protocol is, though, it should not obscure an issue that goes far beyond Northern Ireland – the urgent need for a global security reset, with the US and the UK in the vanguard.

As it happens, former Sunday Times security correspondent Richard Kerbaj has just written a fascinating and very readable history of the ‘Five Eyes’ intelligence agency relationship between anglosphere countries, balanced on a US/UK axis. The book illustrates the development of a special and enduring bond, one which has certainly saved lives by combatting violent extremism. Kerbaj managed to secure interviews with two former prime ministers, David Cameron and Theresa May on the nature and importance of that link.

Cameron was clear about co-operation and the necessity of pragmatism over dewy-eyed idealism (‘I do not hold a sort of romantic view about the capabilities of the UK’), but also firm on what our UK agencies – MI5, 6 and GCHQ – bring to the table.

‘So I don’t think it’s Britain just pretending that we bring something to the Special Relationship, I think it is genuinely appreciated. And I can think of specific incidents, really quite important ones…where there was a very important input from British intelligence.’

May also spoke of the strong intelligence ties that bind the US and UK, whatever the other vicissitudes that drown out or undermine those bonds – or, indeed, the personalities. You get an understated but telling sense of this when she refers to the capriciousness and chaos of the Trump administration:

‘It would be helpful not to have to adjust to something like that, but in a sense we had to start to think about the relationships. The relationships had been going on for so long and there had always been an assumption of smooth running relationships.’

Trump chewed up four national security advisors during his tenure at the White House. Some were duds, others, like General HR McMaster, were precisely the sort of erudite Anglophiles to keep the intelligence relationship healthy. As May went on to tell Kerbaj, the honesty of that brotherhood of secrets is a foundation for the politics that sits on top of it.

‘There is a key, important relationship between the US and UK. You’re talking about the Five Eyes in this book, but obviously at the centre of the Five Eyes is that very strong security and defence relationship…so ensuring that there was nothing that was being said erroneously that could lead to jeopardising that relationship is important.’

The vitality and durability of that security relationship is remarkable. Kerbaj reveals that the first instance of it working at an institutional level was in the late 1930s when MI5 risked compromising a counter-espionage operation by informing the FBI that its target, a Nazi spy, was also planning to attack assets in the US. We go back a ways.

Contemporary global terrorism brutally reinvigorated the special relationship. On September 12, 2001, our three top intelligence officials, flew across the Atlantic ready to assist an ally on its knees in shock – despite US airspace having closed following the previous day’s infamy – and in doing so heralded a golden age of co-operation, exemplified by the Blair/Bush partnership and the ‘War on Terror.’ History had not ended with the fall of communism. The new threat of weaponised theocratic fascism and state-sponsored terror jump-started our joint security and defence effort to go after and defeat despotic regimes, with all the deeply consequential fallout, for good and ill.

Now that special relationship risks foundering on the rocks of mutual suspicion and no little bewilderment at economic moves that have put us close to parity on currency but precious little else . No wonder Liz Truss wants a reset. The jokes flying around between officials that they had retired the phrase until they ‘know what’s going on’ were mostly on us. ‘He’s not that into you’ is not where we want to be with the world’s biggest economy. That ‘special relationship’ isn’t merely a rhetorical comfort blanket either. Keir Starmer’s newly discovered prime ministerial mojo and the fiscal gamble of her new Chancellor must be giving State Department officials who actually control the temperature of our trans-Atlantic love-in some pause for thought.

The Northern Ireland Protocol can’t be ‘fixed’ – the square peg of national sovereignty can’t fit the round hole of a free trade bloc – but it can be almost fully anaesthetised. With some pragmatism from both protagonists that’s probably what will happen. Once that hurdle is finally cleared, perhaps we can have a look at that trade deal again.

More importantly, rules-based liberal democracies have enemies galore, including those with nuclear arms. The West’s enduring strength is much bigger than one bilateral relationship, but it’s still mightily influenced by its vitality. We need to make sure that Biden understands just how much moral authority and intellectual heft the UK can still bring to bear, including in countries where our long-standing presence and relationships are greater than our American cousins.

The world seems a pretty dark, scary place at the moment. Reinforcing the US-UK relationship – ‘special’ or otherwise – would be an easy way to let in a little light.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.