Westminster’s Brexit impasse looks as intractable this week as it did last week, and so MPs are no doubt tempted to consult their employers, the British people, as to what to do next. Some, of course, want to do so formally in a second referendum (more on that later). While the majority of MPs oppose that option, they doubtless have half an eye on public opinion as they decide what their next move should be.

But following the voters’ lead will not get politicians very far. At a UK in a Changing Europe conference yesterday (you can read the associated publication here), Sir John Curtice — arguably Britain’s preeminent political scientist – presented a fascinating survey of public opinion on the crossroads the country finds itself at. His conclusion? That the House of Commons is actually fulfilling its representative function splendidly well in several respects: a clear majority in Parliament and the country oppose the Prime Minister’s deal, and, both on the green benches and out in the country, no one agrees on very much else.

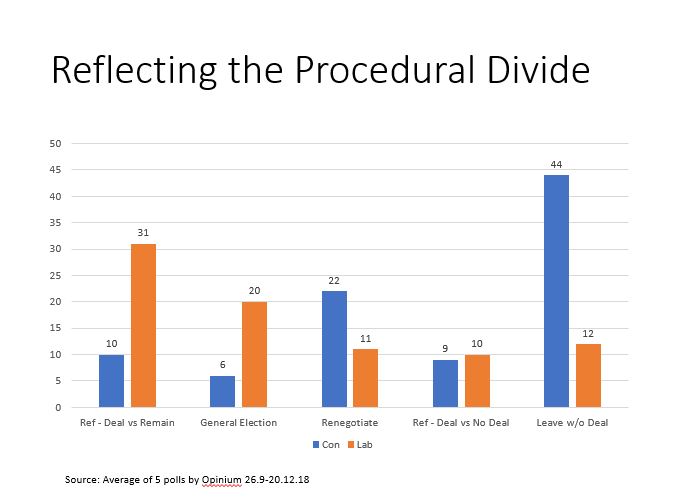

Ask people what should happen next and you get about the least helpful answer imaginable. According to the latest Opinium poll, 22 per cent back a “deal versus remain” referendum, 9 per cent support a “deal versus no deal” referendum, 12 per cent support a general election, 20 per cent support renegotiation and 24 per cent back leaving without a deal.

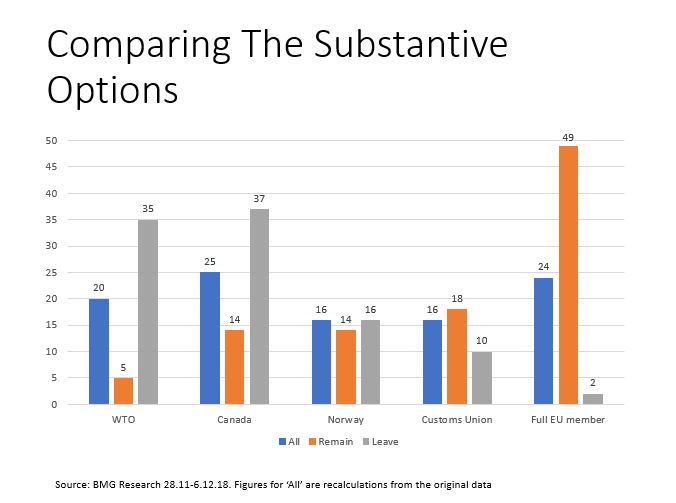

What about the substantive options available to Britain? Here, the answer is no more useful. A fifth of voters back “WTO”, a quarter back Canada, less than a fifth back Norway and customs union membership. A quarter back full EU membership.

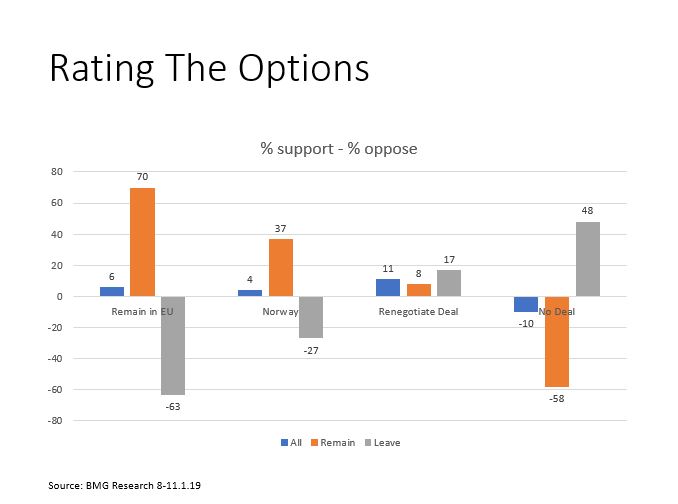

At this point, you might reasonably point out that, given that Brexit will need to involve compromise, looking at voters’ first preferences only gets you so far. Dig into voters’ approval/disapproval of the various options, or factor in second preferences and you soon learn that there are no compromises with much chance of winning widespread support. “Renegotiating the deal” might get a positive score from all sides, but clearly Leavers and Remainers would want very different things from that renegotiation.

When you make the search for middle ground more explicit, asking voters if the various substantive options are a good outcome, a bad outcome or an acceptable compromise is similarly unsatisfactory.

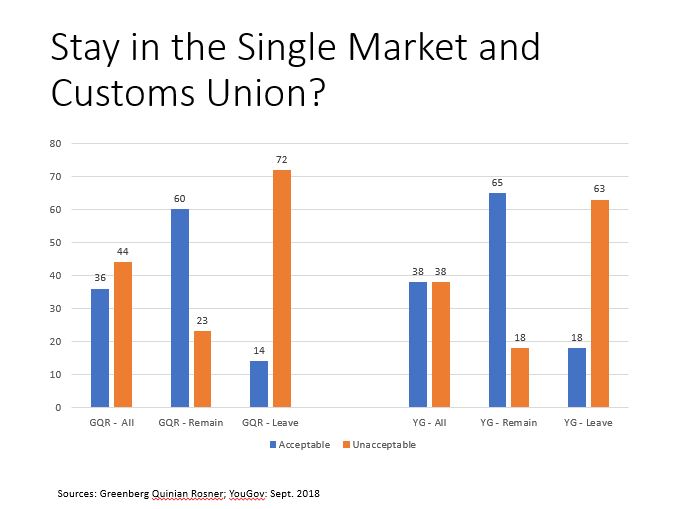

In short, no option passes Professor Curtice’s two-part test for a compromise that satisfies popular opinion: an overall majority and a majority in both Leave and Remain camps. There are Leaver compromises and Remain compromises, but none that bridges the divide. Consider, for example, the breakdown of the (rather tepid) support for remaining in the Single Market and Customs Union, a clear Remainer compromise:

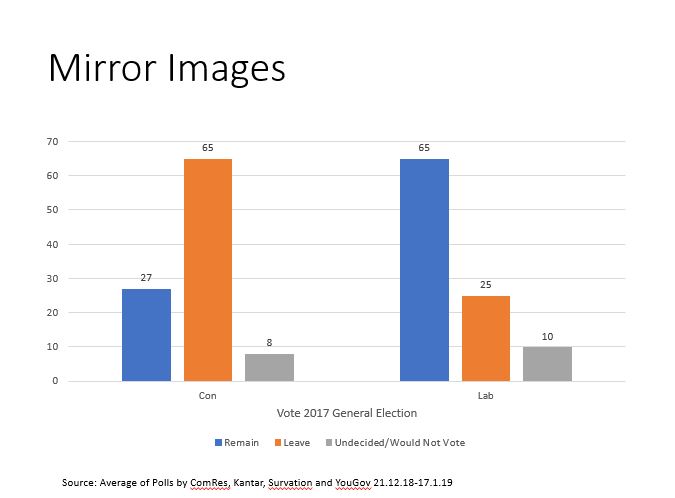

Here there is a striking symmetry between Labour and Conservatives. Jeremy Corbyn and Theresa May lead parties that, in terms of Brexit, are mirror images of one another.

Among both sets of voters, there is a plurality of support for an option at one end of the spectrum: no deal among Conservative voters and a rerun of the referendum among Labour voters.

Both leaders are, in their own ways, searching for a Brexit compromise. But all the signs suggest that such compromises will not go down well with their respective groups of voters. Seeking the centre-ground is often good political advice, but, according to Professor Curtice, it is far from clear that is true when it comes to Brexit, on which the centre-ground is “thinly populated”.

To paraphrase noted public intellectual Danny Dyer, Brexit is as mad a riddle now as it ever has been. And so, in spite of all the principled objections and practical complications, the argument that now is the time for a second referendum seduces more and more by the day. This morning, the Financial Times came out for another vote, arguing that “if the people’s representatives cannot resolve the most momentous political issue in a generation, the people must once again have their say”.

The problem for “People’s Vote” advocates is that people don’t want to vote again. Or at least, not if you’re straight with them about the sort of referendum you want to hold.

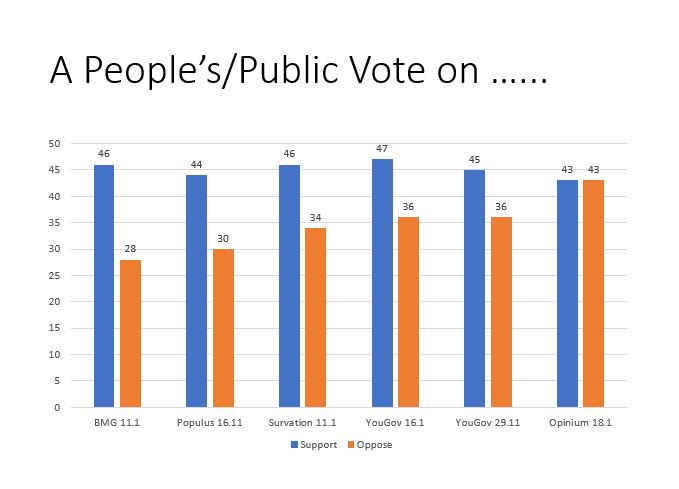

Polling companies have asked voters all sorts of different questions about a second vote, but they fall into two categories that produce very different results. Here’s what voters tell you if you ask them whether the public should have a say on the final deal (or some variation of that):

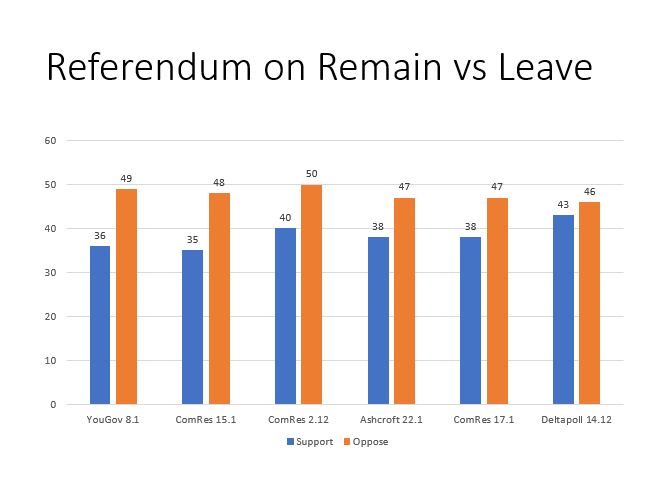

These are the polls that People’s Vote activists are fond of quoting. Indeed, many of them were paid for by the People’s Vote campaign. This, however, is not the sort of vote they’re actually arguing for. They want to stop Brexit, and to do so in a second referendum with ‘Remain’ on the ballot paper. Phrase the question more honestly and the results look rather different:

According to Professor Curtice, the clear pattern is that “if remain is an option, we cannot argue that there is clear support for a second referendum”.

And the one clear conclusion that can be drawn from the avalanche of polls conducted in recent weeks is that were such a vote to take place, far from offering any kind of clarity, the voters’ verdict would only muddy the Brexit waters in Westminster yet further.

All charts courtesy of John Curtice and UK in a Changing Europe.