Most macroeconomic forecasts contain a few gremlins – questionable assumptions or inconvenient details – that help nudge the underlying model towards the results its authors or patrons want to see. The ‘Economic and Fiscal Outlook’ (EFO), published on Budget days by the OBR, is no exception.

Since the OBR was created in 2010, it’s become something of a Budget day tradition for economists and policy wonks to hunt through EFO spreadsheets in search of the latest aberration. In the October 2021 Budget for example, the gremlin was implausibly high productivity growth (twice the average in 2010-19) which in turn underpinned some pretty favourable GDP forecasts. This was noted by the CPS in our ‘The Age of the Trillion-Pound State’ briefing.

Pointing this out mattered because tax and spend is substantially predicated on economic growth, and productivity was a key pillar of forecast economic growth in that Budget – knock it away and the whole superstructure of fiscal and macroeconomic policy would come tumbling down (supply side reforms were therefore vital, we argued). Given the centrality of the Budget to our political economy, a small gremlin hidden in column D of sheet C2.28 of Excel file 2/10 can thus have massive policy implications and political consequences.

So what of Jeremy Hunt’s Budget on Wednesday? Well, in this case, the insidious figure lurking within the accompanying data was not exactly difficult to find, for it was the same as in the November 2022 Budget, only bigger – 19.5% bigger, to be precise.

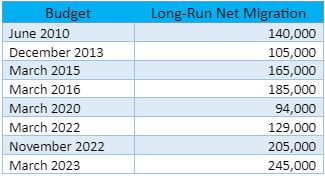

Lots of factors go into GDP growth. One is the size of the labour force. Hunt’s welcome push on economic inactivity was partly a reflection of this. But most of the workforce growth comes from additional net migration, with the long-run annual rate revised up by 40,000 to 245,000. This is the highest level ever in OBR forecasts, as per the table below, which is based on analysis of all 27 EFOs to date.

.

The OBR figures are generally taken from ONS population projections, so it’s not solely the OBR pulling the levers here, though it decides which of the low, principal or high ONS projections to use. When George Osborne was Chancellor, it switched between the principal and low cases, cohering with the rhetoric of immigration control across government (though the forecasts did not reflect reality). Had Kwasi Kwarteng waited for an OBR analysis of his mini-Budget, it would undoubtedly have gone with a high case, giving him better economic numbers to work with.

Hunt will be happy with an ONS principal projection that has been revised upwards, for this gremlin steps in to save the day at the end of the forecasting window. GDP growth in 2027/28 is hit by the end of full expensing and a drop in business investment. But the cumulative effect of higher net migration cancels this out, sustaining GDP growth of 1.9% instead of 1.4%. And so, through accounting alchemy, helps the Chancellor to stay within his self-imposed fiscal constraints and reassure the bond markets.

Compared to the November EFO, cumulative migration in the forecast period is up from 1.3 to 1.6 million. We can infer that the OBR thinks every 60,000 migrants yields a 0.1% GDP annual boost. But even if this relationship holds, GDP growth is not the same as GDP per capita growth.

Clearly some sorts of immigration – high-skilled workers who move to cities and feed agglomeration effects – can boost GDP per capita. But the additive migration of low-skilled workers of the past two decades has not. Our current immigration regime is really just more of the same. In theory, under the points-based system, we’re supposed to be prioritising skilled workers. But the salary threshold for a ‘skilled’ worker is set at just £26,200 – 20% lower than the median wage.

As per the Migration Advisory Committee, there is a solid body of evidence to show sustained low-skilled immigration has held back business investment. Indeed, as robotics expert Rian Whitton ceaselessly points out, the UK has the lowest level of automation of any major developed economy. Perhaps the full expensing announced by Hunt will lead to more productivity-boosting tech in British workplaces. But as the latest EFO shows, we’re still a long way from adopting the high-skill, high-wage economic model politicians wax lyrical about.

Meanwhile, we’re not building enough houses to keep pace with even endogenous population growth under a net zero migration regime, let alone what is anticipated in the budget. And with newcomers tending settle in clusters, there are also broader effects on public services like GPs, dentists and schools – more geographically concentrated demand, but not more supply.

So while mass migration of the sort built into the Budget may or may not grow GDP in line with the OBR projection, thanks to investment disincentives and congestion effects, it certainly won’t drive an increase in real living standards. After all, the longest sustained period of mass migration in modern British history coincides with an unprecedented period of stagnant productivity and feeble per capita growth.

And what about the electoral consequences of continued mass migration? The OBR now assumes long-term net migration running at 260% of the rate anticipated when we finally left the EU (94,000). In all probability, as the public cottons on to ongoing mass immigration, this will deepen public distrust in politics in general, and further alienate swathes of the 2019 Tory electoral coalition in particular.

This is borne out by polling carried out for the CPS report ‘Stopping the Crossings’, in which fully 59% of people thought immigration was too high over the last 10 years; only 9% thought it was too low, while 26% thought it about right. Unsurprisingly, 74% of people who voted Conservative in 2019 thought immigration was too high.

They did so to stop Jeremy Corbyn, and to get Brexit done – to ‘take back control’. Thus the 2019 Conservative manifesto promised not just an ‘Australian-style points-based immigration system’ post-Brexit, but also, crucially, that ‘overall numbers will come down’.

Not only has that promise been broken already – net migration is running at over half a million a year, the highest level on record (even if Hong Kongers, Ukrainians and Afghans are taken out of the figures) – but, crucially, the OBR forecasts show that the Government is implicitly doubling down on a political economy that is incompatible with Conservative manifesto promises.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.