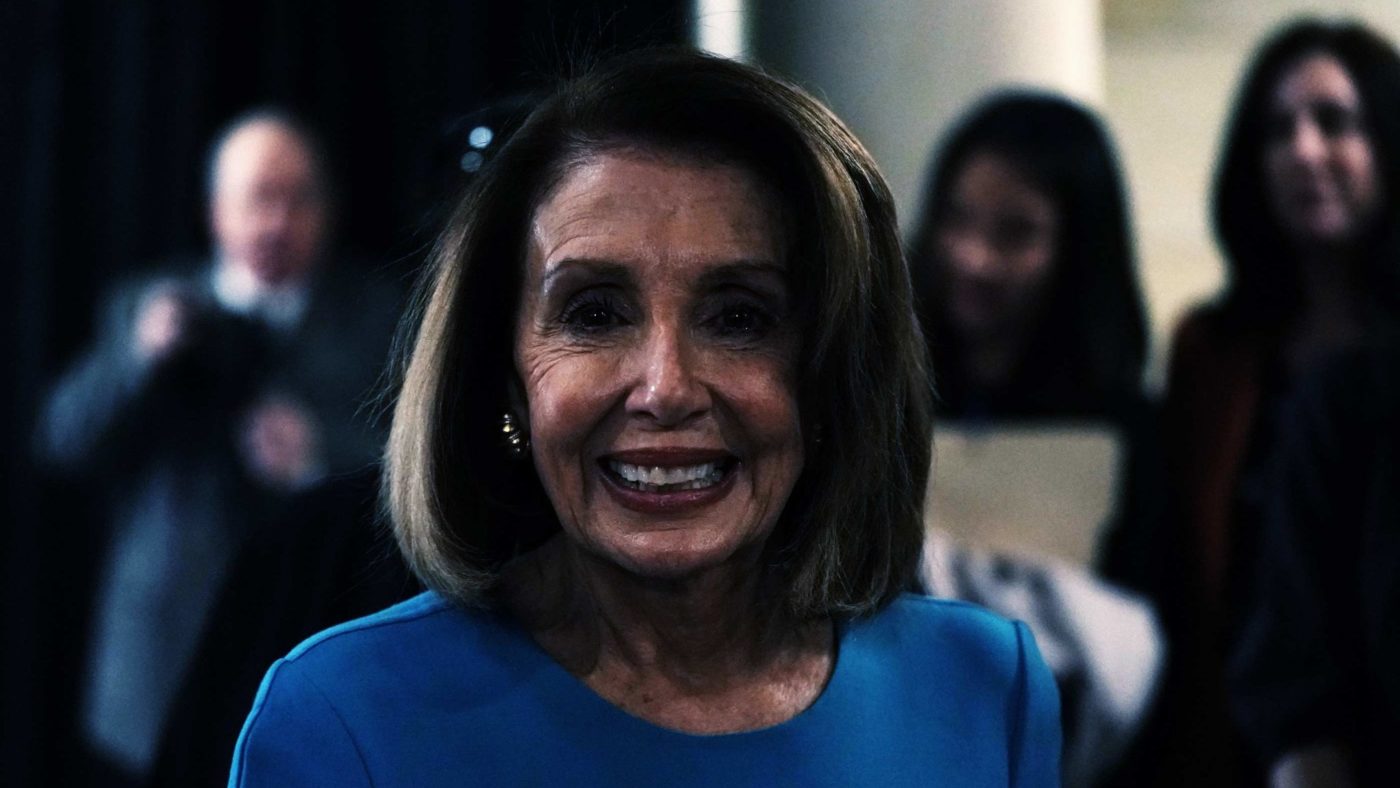

It is the fate of successful party managers to be liked by no one, but to be indispensable to all. Last Wednesday, Nancy Pelosi won the House Democrats’ nomination for the next Speaker of the House. Her majority, 203 votes to 32, shows how she has managed to stay on top in her party, not least by rendering herself indispensable to the other party managers. For the same reason, it suggests that she is becoming dispensable.

Pelosi’s nomination has a certain logic. She has served as Minority Leader in the House of Representatives since 2011. The Democrats flipped the House in November’s midterms. So who better to serve as Speaker?

Social scientists have a name for this logic: path dependency. Institutions, like the people who run them, are creatures of habit. They perpetuate themselves beyond their useful span of service, because part of their service is to reward the people who work for them. Since the 1990s, the institutional habits of the Democrats have been centrist and technocratic. The party’s management has pursued two Clintonian triangulations.

Internally, the Democratic leadership has triangulated the needs of its two biggest bloc votes, the unions and African Americans, with its own need to cultivate the donor class. Electorally, it has mirrored this strategy by promising protection and welfare, but without raising taxes to a level that alienated Wall Street.

Pelosi, a well-heeled limousine liberal from California, is the quintessence of these strategies. Indeed, her rise to indispensability is a product of them. So too was the sudden rise of the inexperienced Barack Obama, who promised an expansion of the state on a scale not seen since FDR, while drawing unprecedented donations from Wall Street. That allowed Obama to run for the Democratic nomination as the opposite of Hillary Clinton, but to run for the presidency as the second coming of Bill Clinton.

That was a smart strategy, but who now reckons that Obama is still the smartest guy in the room? No one. There are three reasons for that, and all three will determine what happens next to Nancy Pelosi.

The first reasons is that the voters lost their appetite for the Clintonite trade-off in late 2007. Overnight, mortgages and pensions, the middle-classes hedge against penury, lost value. The great triangulation was meant to offer economic stability and upward mobility in the age of globalization. It turned out to deliver the opposite for many Americans, especially those without accumulated family assets, and those on the lower rungs of the property ladder.

The second reason is that the fruits of the recovery that followed were not shared. There has not been a better time to be rich in America since the Gilded Age. Nor, with the expansion of the state into the healthcare business, has there been a better time to be poor. But this is not a great time to be middle class. And as more than 80 per cent of Americans consider themselves to be middle class, that creates problems at the ballot box.

The third reason is that dissatisfaction among the party membership is reaching critical mass. This is a generational difference, which is inevitable. But it is also an ideological difference, some of which might have been avoidable. Again, the explanation lies in the crash of late 2007, which discredited the Republicans, and the Obama campaign, which delivered more hope than change.

Ideologically, Obama’s candidacy was a bait-and-switch in the way of almost all presidential campaigns. Obama nodded to the extremes to win the party nomination, then aimed for the centre in the general election. The amount of money required to run an election campaign forces this manoeuvre on all candidates — unless, of course, they can fund themselves, as Donald Trump did in 2016.

The problem for Pelosi and the centrist Democrats who control the party is that the centre no longer holds. In 2016, Trump proved that the the extremes were collapsing into the centre, through a combination of economic despair, cultural resentment, and the translation of politics into the digital continuum. This, though, merely confirmed what Obama had tested in 2008.

It was Obama, not Trump, who first to bypass the party managers by mobilising the grassroots on the internet. It was Obama, not Trump, who was first to promise to disentangle America from Cold War obligations and Clintonian interventionism. And it was Obama, not Trump, who was first to promise to rebuild America with the dividend.

This continuity goes unacknowledged, because partisanship means never having to say the whole truth. But the truth of this continuity is that Trump’s successes have been boosted by Obama’s failures. Obama’s presidency stabilized Wall Street, and Trump’s, by lucky timing and tax cuts, set the record for the longest bull run in American history. Obama’s presidency did not do as much for the middle class. It did, however, talk a good game when it came to rallying and soothing sectors that depended on the Democrats’ institutional path dependency, and had been on short rations since the Clinton presidency.

Which is how identity politics and protectionist economics entered the Democratic mainstream after 2008. A similar process was afoot in the Republican Party, where the Tea Party offered identity politics for white people, and also accused its party managers of exposing workers to globalisation.

In 2016, Trump campaigned towards the extremes, and pulled the older, whiter centre with him. The 2018 generation of Congressional Democrats — Alexandria Ocasio-Cortes, for example — believe that their party can do the same with a youthful demographic and a rainbow coalition. It is not clear how much longer the Democrats’ minorities will consent to be represented in Congress by Pelosi, who is rich, white, and a 78 year-old friend of the Clintons.

Hence those 23 dissenting votes when Pelosi sought the nomination. Only one House race remains to be called from November’s midterms. If the Democrats win it, Pelosi could afford to drop 17 votes and still reach the Speaker’s chair. Some of the dissenters have affirmed that they won’t vote for her. On Friday, Anthony Brindisi of New York’s 22nd District confirmed that he had told Pelosi he wouldn’t break his campaign promise to oppose her nomination.

In 2017, when ex-Nation of Islam Jew-baiter Keith Ellison secured the grassroots’ support as a candidate for chairmanship of the DNC, the older centrists managed to block him. The DNC chair is Tom Perez, who has leftish credentials — he was Obama’s last Secretary of Labor, and he has a Hispanic background, albeit for the non-leftish reason that his grandfather was the Dominican ambassador to Washington.

I suspect that Pelosi and her friends will pull off a similar move before the House vote on January 3. Some Democratic dissenters will be brought or forced around. Others who haven’t yet played their hand will leave their ballots blank. Still, coercion, and the fear that the party will split just as it has recovered its legislative bite, will be more than enough to push Pelosi past the threshold of 218 votes. But don’t expect Pelosi to keep the job after 2020, and not just because she will be 80 in 2020. The times, and the ideological mood, have already changed in the Democratic Party.