There is a story the British political class tells itself about immigration. It goes like this. Labour’s decision to open the door to Eastern Europe was, everyone now accepts, a mistake. True, it provided that same political class with delightfully cheap plumbers, builders and cleaners. But it also put pressure on public services, strained community cohesion, and stoked resentment among the white working class. The problem was made worse by the way anyone who expressed concern was labelled a racist, from Michael Howard down.

Now, however, things have improved. Yes, immigration has bounced back to record highs. But at least politicians are talking about it, and are – at least in theory – pledged to tackle it. Worrying about the number of new arrivals is no longer the province of “bigoted old women” like Gillian Duffy. The political system has got the message.

This narrative is comforting – and utterly, completely wrong. The truth is that there is a yawning chasm between how worried voters still are about immigration, and how seriously politicians take it. And this phenomenon could end up being what tips Britain out of the EU.

Earlier this week, in response to a public petition, MPs spent three hours debating Donald Trump’s views on Muslims – or rather, condemning them. The prevailing spirit was one of back-slapping congratulation on the marvels of multiculturalism: as I wrote in a sketch for Politico, Trump was invited to visit enough mosques and curry houses to fill his schedule for months.

Of all the MPs who spoke, only Philip Davies, of Shipley in West Yorkshire, pointed out the inconvenient truth: that Trump’s views are shared by a large chunk of the British public. A quarter of voters told YouGov that they thought the US should indeed ban Muslims; in the North of England, the total was 34 per cent.

The taste of humbug was even stronger when you looked at the rest of the petitions before MPs. It turned out that the second most popular, with more than 450,000 signatures, called for Britain to close its borders not just to Muslims, but to all immigrants, until ISIS is defeated. Yet while the parliamentary committee that runs these things leaped to schedule the Trump debate – with its opportunities for delivering pious platitudes in the glare of the media spotlight – it has yet to set a date to discuss this other issue. Even if it did, it’s hard to think of a single one of Britain’s 650 MPs who would argue in favour.

Alarm about immigration isn’t a fringe position. It never has been. A new book by Ben Judah, called This Is London, lays out in stark detail how immigrants (many of them unrecorded) have taken over large parts of the capital. Even according to the official figures, net migration, which the government had pledged to bring down to the “tens of thousands”, is running at record levels.

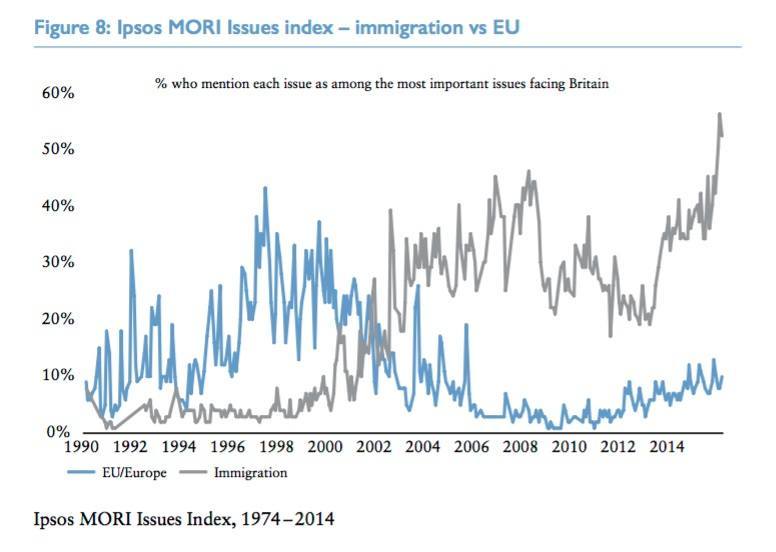

As a result, public concern – and public anger – have been rising remorselessly. A new pamphlet on the European debate from the think-tank British Future shows the trend over time. The final spike, of course, coincides with the migrant crisis in Europe – which could very well be repeated this year once the weather improves.

What might the consequences be? You have only to look at the effects that anxiety over migration has already had. It spurred the rise of UKIP, which in turn pushed David Cameron into conceding an EU vote to shore up his right flank. As the British Future study says, “It is fair to say that the main reason we are having this referendum is, in a word, immigration.”

Worry about immigration will, therefore, have a huge role to play in the battle over Brexit. When I interviewed Arron Banks of the Leave.EU campaign, he told me: “We’ve done a huge polling exercise and analysis, and even for the undecideds – at a rate of 15 to 1 – the concern is immigration and security.” Voters, he said, brought it up “again and again”.

The most obvious consequence of this resentment will be to swell the Out vote in the EU referendum. But even leaving the EU might not be enough to assuage the public’s concerns. Much of the Outers’ case is based on a promise that Britain will still trade freely with Europe – but as the arrangements negotiated by other EU refuseniks show, it is impossible to have free markets without free movement. Plus, part of the Eurosceptic pitch is about liberating ourselves with Europe to trade with the world – does that mean replacing EU immigrants with a similar number of new arrivals from the former Commonwealth?

The Out side may have to choose, in other words, between offering an “open” vision of Britain’s future and a “closed” one. (This, indeed, is broadly the division between the two rival anti-EU campaigns.) And the In side will also have to explain to voters how they will do more to address the consequences of mass immigration – since they will be just as powerless as they are now to tackle its causes. David Cameron’s suggestion to restrict access to benefits for several years may be economically irrelevant – the overwhelming proportion of migrants come to work, not freeload – but it strikes a chord precisely because it appears to make things a bit fairer.

The ultimate issue here goes beyond EU membership. It is that Britain has gone from being a low-immigration country to a high-immigration one – and there is no realistic prospect of that changing any time soon. Even if we left the EU, immigration from the rest of the world is already running into the hundreds of thousands. Even if politicians can change the rules, the strength of our economy and the growing numbers of migrants from Africa and the Middle East are sure to pull many more in, legally or no.

The problem is that the political class – and especially those of us who broadly favour immigration, and have broadly benefited from it – have done a pisspoor job of explaining this to the voters, or reconciling them to it.

The reason is that, for both left and right, this cuts across deeply held beliefs. The Conservatives have spent 30 years preaching the virtues of open markets – a commitment which has consistently trumped their concerns about open borders. For Labour, restricting immigration is a right-wing, Little England policy which goes against their commitment to human rights, international co-operation and helping the oppressed.

The result, as mentioned above, has been a growing divide between Westminster and the rest of the country. We may not be in a position yet to breed our own Donald Trump – even Nigel Farage said he thought he’d gone a bit far. But anyone who considers Britain’s problems with immigration to be solved, or contained, is sorely deluding themselves.