The impeachment of Donald Trump is clearly merited. Short of treachery in the service of a foreign power, there can be no greater abuse of office than encouraging insurrection against constitutional government.

It may seem odd, therefore, that the comparatively inconsequential issue of banning Mr Trump from social media should excite comment. Yet it ought to. There’s a better case for allowing him to scream into the online void than there is for sparing him the obloquy of a Senate trial.

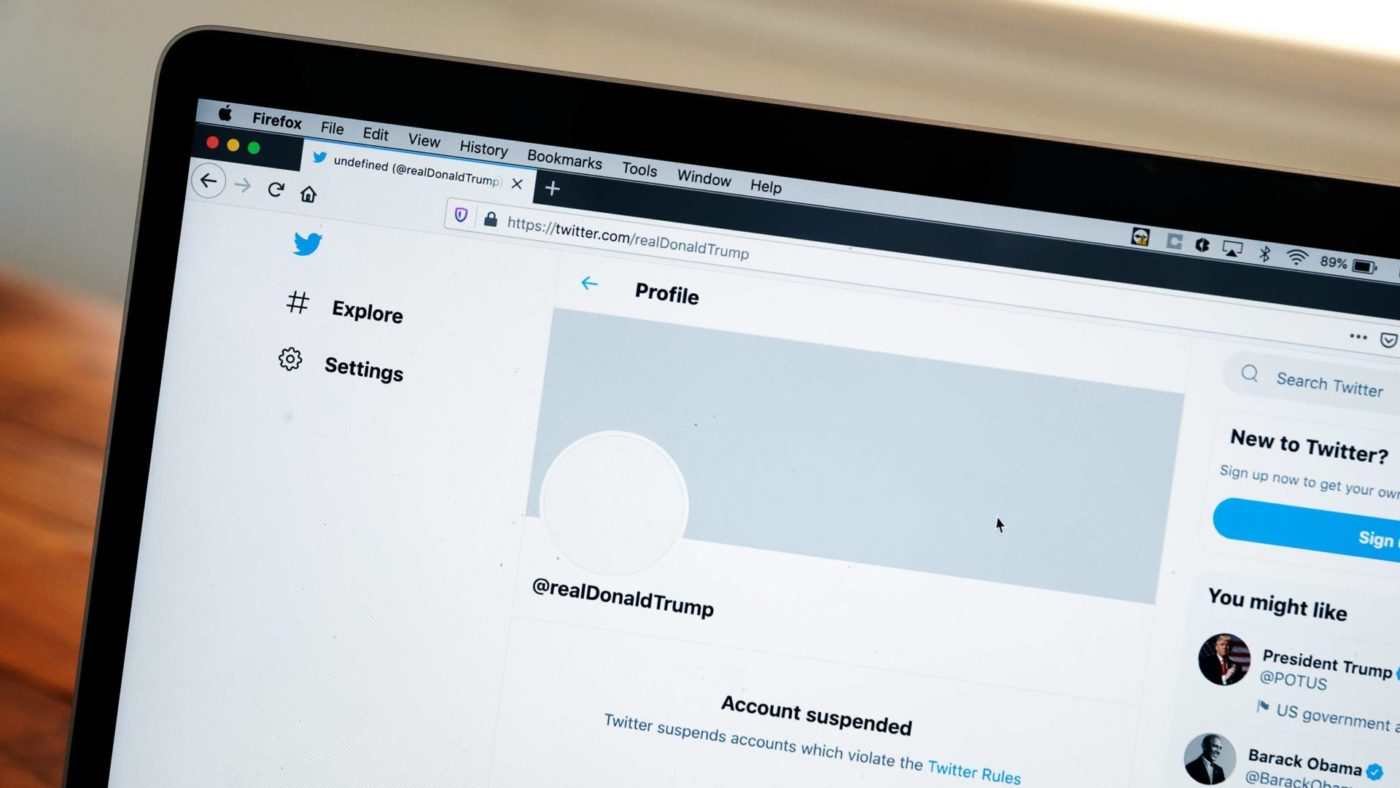

The issue arises because Trump was permanently suspended last week from Twitter and Facebook, while the site Parler – used by many on the political fringe that supports him – was removed from the Apple and Google app stores. And, however much it rankles to say so, these actions do raise a free-speech issue. It’s not a straightforward one and it certainly doesn’t accord with the self-serving victimhood of the US right, but it shouldn’t be brushed away.

Social media has many benefits in bringing people together, but in the political sphere it is an appalling place. For anyone with even a small public profile, like us newspaper columnists, it is a constant source of abuse and harassment. My approach to the problem is unhesitatingly to get people banned from Twitter for this sort of behaviour. The number of accounts I’ve had taken down is well into three figures. Here’s an example. I wrote for CapX last year about a typical case of such behaviour: a man in the north-east of England called David Lindsay, who sent me an anonymous death threat and now has a suspended sentence and indefinite criminal behaviour order for trying the same thing with public officials. Rather than being dangerous, he’s a morbidly obese fantasist in his 40s who has no job and lives with his mother.

People like this have no inherent right to post on social media. To insist that they do is to confuse the right of free speech with the right to use a particular platform. And what is true of obscure losers in the lottery of life is true of better-known people too. The suspension from social media of David Icke, the conspiracy theorist, is completely justified when he spreads systematic disinformation about the coronavirus crisis. His fantasies may cost lives. Covid denialists in the United States have certainly done this, as reported by the admirable BBC specialist correspondent on disinformation, Marianna Spring.

And then there is outright violence. When it comes to free access to conduits of information, an observation advanced by Conor Cruise O’Brien stays with me. The great historian and polymath served in the Irish government in the 1970s, in which capacity he cracked down on the ability of terrorist groups and their supposedly political front organisations to broadcast their propaganda. Speaking to the Irish Senate in 1975, he said: “I know that, in certain circles, it is regarded as somewhat ‘paranoid’ even to refer to armed conspiracies. It would indeed be paranoid if these conspiracies did not exist. Unfortunately they do exist…”

There is an unassailable case on the second and third grounds I’ve mentioned to suspend Trump from social media for the rest of his presidency, which will mercifully end next week. His output decrying supposed electoral fraud is itself fraudulent. And he deliberately stokes and inflames the anger of his supporters, who have committed violent and lethal insurrectionary acts. Of course this stuff should be clamped down on in these febrile times. The tech giants have a duty to do this, in order to maintain public order during a transition to a new US administration. This is justified on grounds of defusing a clear and present danger of mayhem and murder.

But what, then, happens, when Trump passes into private citizenship (and hopefully indictment)? That longer-term issue is more troubling, as it underlines how far civic life has been shaped by social media. Political discourse is now played out far more in these forums than it is in media that are researched, edited and accountable, such as the newspaper I work for. That, to my mind, is pure loss, and it involves a citizenry that is more insulated from information and debate. But it’s a fact. And I don’t trust those who hold the reins of social media to exercise wisdom in policing the boundaries of legitimate exchange. There has been, throughout the rise of these corporate behemoths in the digital age, a naivety about the repressive power of private organisations.

I have long been a sceptic even of the idealistic project of Wikipedia, for example, which seeks to make knowledge available; my objection is that by design it prizes consensus over accuracy. In a risible, rambling series of tweets yesterday justifying the suspension of Trump, the chief executive of Twitter bafflingly referred to his belief in Bitcoin as an instance of the power of the online ecosystem. If this speculative fad is the best philosophical justification they can come up with, then the case for anti-trust legislation to break up such concentrations of power becomes overwhelming.

I don’t want a political figure of regrettably substantial support to be subject to the caprice of tech companies. It’s worth noting that the heroic dissident Alexei Navalny, who has lately survived an assassination attempt by the Putin regime, is disturbed by the ban on Trump. What can be done by a a private company can easily be replicated and justified by an autocratic state. Trump is a disgrace and, for the moment, a public danger – but when he gracelessly passes into private life, Twitter should let him speak again.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.