Well, that escalated quickly.

On Friday, I was the proud publisher of a policy – long-term, fixed-rate, low-deposit mortgages – that Boris Johnson had decided to put at the heart of his attempts to help “Generation Buy”. By Saturday, the same policy was being condemned in some quarters as putting Britain on a path to a repeat of the financial crisis – or at the very least being a recipe for rampant house price inflation.

So what exactly is being proposed? And why do I still think it’s an utterly brilliant idea?

Let’s start at the beginning. In December 2019, the Conservative manifesto contained a promise to introduce these mortgages to help first-time buyers on to the property ladder. It was inspired by the work of the Centre for Policy Studies, and in particular Graham Edwards, the successful entrepreneur and philanthropist who serves as chair of our Housing Policy Group. Shortly after the election, we published his paper ‘‘Resentful Renters’, which set out the case that Boris only sketched in his Daily Telegraph interview (in places, in slightly garbled fashion).

It all starts with the financial crisis

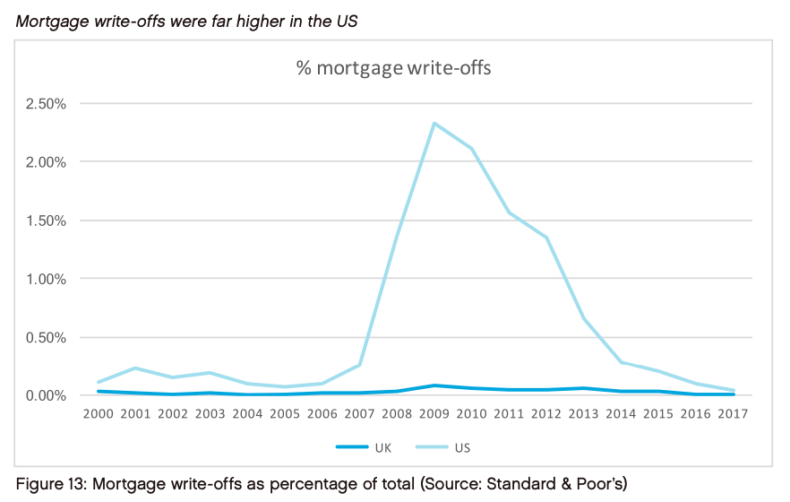

The analysis starts with the financial crisis – driven by wildly extravagant lending to unsuitable borrowers, primarily in the US.

.

In the UK, regulators (and lenders) responded to the financial crisis in two ways.

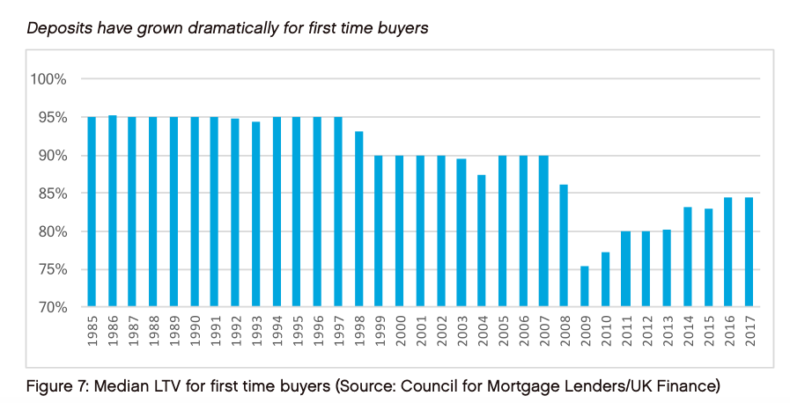

First, they sharply tightened deposit requirements – actually a bit of a red herring, since subprime loans in the US were generally made at much lower LTVs. They didn’t just cut out Northern Rock-style mortgages of 100% or more – the average deposit required soared from its long-term average of 5% to 25%, before slowly rising back to approximately 15% today. (This was partly a commercial decision by banks, and partly forced by Bank of England rules about the blend of lending they are allowed to issue.)

Next, the Bank of England imposed a new ‘stress test’. It wasn’t enough that you were able to afford to pay a mortgage at whatever rate the market was offering. You had to be able to afford the costs once that mortgage reverted to the Standard Variable Rate – plus another 3%.

Graham’s research found that the average rate used in affordability tests was 7.26%. This compares to the average actual mortgage cost of 2.35%. So, in 2018, the average first time buyer was paying a monthly mortgage payment of £633 – but only if the computer said that they could actually afford to pay £1,075 a month.

There was a prudent logic behind the stress test. One of the triggers of the subprime crisis in the US, as Graham’s report showed, was “teaser” mortgages in which borrowers suddenly faced massive spikes in their repayment costs once the initial term ran out – and simply walked away from the properties.

It should obviously be the case that buyers are able to cope with shocks, and that people with mortgages are not taking on more borrowing than they can afford – or perching on the ragged edge of affordability, ready to fall off at the slightest shock.

But the combined effect of these two measures, utterly unsurprisingly, was to yank home ownership out of the reach of an entire generation – and create a cavernous divide between those with the resources to pay the new higher deposits (often thanks to the Bank of Mum and Dad) and those without.

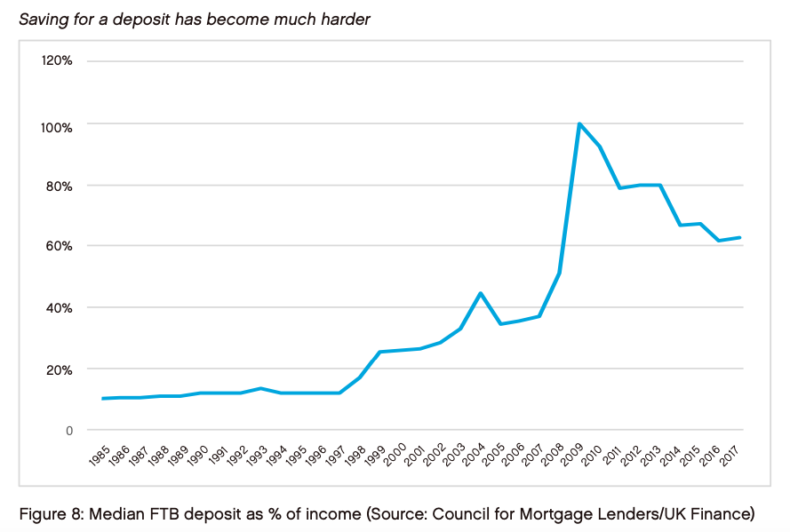

The average deposit went from costing 40% of average income in 2008, to 100% in 2010, falling back to 60% by 2017. And as our research showed, this was driven overwhelmingly by regulation, not by house price increases.

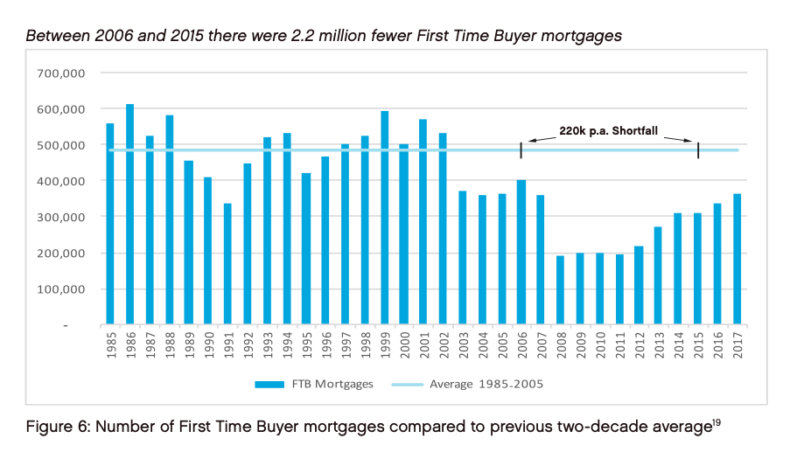

These changes also tilted the housing market drastically towards buy-to-let. Graham’s research showed that there were 2.2 million fewer first-time buyer mortgages issued between 2006 and 2015 than in the previous decade – at the same time as buy-to-let landlords increased their share of the property market from 2.7 million homes to 4.8 million. This more than swallowed up the increase in stock via housebuilding.

.

How to help ‘Generation Buy’

Traditionally, we think of housing affordability in terms of house prices, but the key obstacle for people is actually deposits.

When we were getting the CPS’s home ownership work started, we carried out some focus groups on public attitudes. Those who’ve done focus groups will know that ordinary people never talk about policy – the Australian-style points system for immigration is one of the very few ideas that will emerge organically from conversation. But it was striking that the idea of returning to 100% mortgages emerged in all of our groups as the only way to help people get on the ladder.

Our view at the CPS – which is shared within government – is that the Bank of England’s mortgage stress tests are there for a reason. No one wants a British edition of subprime.

But the beauty of long-term, fixed-rate mortgages – in which you know what you’re paying not just this year, but 25 years in the future – is that you don’t need the stress test, because there’s never any stress. In other words, there is no need to check whether people can afford a sudden massive spike in their mortgage repayments (to SVR + 3%) because the structure of the mortgage makes it impossible: you will always be on a fixed rate, not a variable one.

In fact, these mortgages are more secure against economic turbulence than the traditional model – and indeed against negative equity, because over the longer term the value of the property is (if history is any guide) near-certain to recover. And of course the LTV will fall over time as people repay more of the mortgage.

But the greatest misunderstanding in some of the criticism this weekend is around deposits – and in particular the idea that by loosening requirements you will open up the mortgage market to all sorts of imprudent lending. Basically, that Boris Johnson will be handing cheap government-backed mortgages to Red Wall voters who can’t afford to repay them, in an exact mirror of the subprime fiasco.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

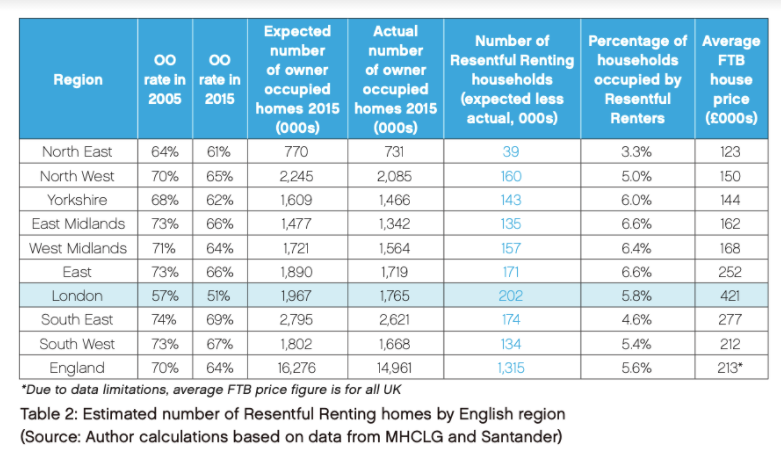

Graham’s key point – and the reason the report is titled ‘Resentful Renters’ – is that the changes after 2008 have artificially distorted the market. We identified 3.6 million people – spread all across the country – who would have been homeowners pre-2008, but now are not. These are normal, hard-working people with good jobs and good prospects. Income-wise, they are identical to the people who actually have mortgages, and their financial prospects are just as solid. The problem is that they do not have the lump sums to pay the new, higher deposit rates – the ladder that takes you up the home ownership cliff.

The calculation in our original paper was that you could offer our long-term, fixed-rate mortgages at 95% LTV rates to an estimated 1.9 million households without any dilution in mortgage standards at all. You would be fixing an existing market failure, not relaxing lending criteria. And in the process you would be locking in – and democratising – today’s ultra-low interest rates so that ordinary people could benefit from them, rather than just those lucky enough to already have assets.

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, the need for this policy is even more urgent. Mortgage lenders have responded to the crisis by hiking deposit requirements yet again, to 20%. We are in danger of repeating exactly the mistakes that crushed home ownership in the wake of the financial crisis.

Any objections?

The irony of the reaction in some quarters to Johnson’s comments is that our original report finished by listing – and demolishing – pretty much every one of the objections that are currently being made. But it’s worth running through them again, given that so many people are apparently coming fresh to the idea.

Won’t this just stoke house prices, as more demand chases the same amount of supply?

In isolation, yes. That’s why we need to build more houses – hence the Government’s planning liberalisation – and incentivise buy-to-let landlords to sell to owner occupiers, for example via the CGT break proposed in this CPS paper.

More generally, this is much less of a short-term concern. These mortgages are not going to flood the market any time soon – it will take time for these products to be developed and distributed and they will sit alongside traditional mortgage lending.

Won’t there be lending to unsuitable people?

No – that’s the entire point! This policy is designed to make mortgages accessible to those who can afford mortgages but not deposits – or at least not the current sky-high deposits.

Will the stress tests be ripped up?

Boris seemed to allude to this in his Telegraph interview – but it’s not in our version of the policy, and I’d be very surprised if the relevant departments or the Bank of England are going down that road. The entire point of the policy is that you don’t need to change the stress tests, because it cuts out the stress.

What about the idea of Government guarantees? Isn’t that just Freddie Mac 2.0?

Again, that’s not in our original version of the policy. Given the Government has spent roughly £12 billion on Help to Buy loans – in which it directly takes on the risk between 75% and 95% LTV – there is a precedent for such intervention. But we’re really not talking here about a Boris Bank forcing through loans to the uncreditworthy.

What about inflation/negative equity/house prices falling?

As mentioned above, these mortgages are actually more secure against financial shocks than those on the market. Also, there’s a crucial difference between the UK and US – in the latter mortgages are tied to the property, whereas here they are tied to the individual. The evidence is pretty strong that even when people here go into negative equity they don’t abandon the house or mortgage – in 2008 the number of defaults and repossessions was a tiny fraction of the US total.

.

What’s more, the fixed-rate nature of the scheme, and the fact it would be limited to those with solid fiscal credentials, means that people will have certainty over their long-term costs and the lenders will have certainty over their long-term prospects. (In fact, if there’s a spike in inflation, the holders of these mortgages should do very well indeed.)

If this is such a good idea, why isn’t the market doing it already?

Partly because interest rates have never been this low. But in fact, as our report shows, this has been popular when it’s been tried – and is the basis for mortgage funding in several other countries.

The problem here is twofold. First, the big banks borrow largely on short-term variable rates, repayable over a relatively short time period (five years, say). They therefore prefer to lend money on a similar basis, to ensure they don’t face a funding squeeze. But there are plenty of institutions (pension funds, for example) which are funded and which lend over much longer time horizons. As part of our research we spoke to several such institutions and found strong interest – if the Government signalled that it welcomed the creation of such a market.

The second problem is more obvious: 71% of mortgages in the UK are sold via intermediaries rather than direct from the banks. It is obviously more profitable for all concerned to sell you a new mortgage every five years rather than one mortgage every quarter-century.

In other words, this isn’t a case of the Government knowing better than the free market. It’s a case of improving a market shaped, and distorted, by Government regulations, and by incentives that work against the best interest of the consumer.

And if you have any other questions, just read the original report. They’ll almost certainly be addressed.

In conclusion…

Long-term, fixed-rate, low-deposit mortgages are a great idea, and it’s hugely welcome that Boris Johnson is so keen on them. They correct a significant market imbalance, and should help to bring home ownership within the reach of thousands of families who have worked hard and done the right thing, but been priced out through no fault of their own.

As the deposit hikes in the wake of the pandemic threaten to make home ownership even harder to achieve, it’s good news that the Government has this problem on its radar – and is thinking along exactly the right lines.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.