Following on from the liberalisation in the 1980s, Britain’s energy system is operated by private companies. Responsibility for energy networks lies with National Grid and a series of privately-run electricity and gas distribution networks. Private companies also handle the generation of energy and retail services to customers.

Jeremy Corbyn plans to change all of this. Labour’s 2017 manifesto made it very clear that he intends to nationalise the energy transmission and distribution networks, of which the upfront would be at least £55bn. This figure relates the Regulatory Asset Value of energy networks (effectively the net invested capital for regulatory purposes). It is well below the commercial price of the listed companies involved and should therefore be treated as an absolute minimum cost of bringing the energy networks into government ownership.

The upfront cost could also go up, given this may not be the limit of Labour’s plans for nationalisation in the energy sector. Even though it is not currently Labour Party policy, Corbyn has previously talked up the possibility of nationalising the Big Six energy companies, which account for over 80 per cent of the electricity market and 65 per cent of Great Britain’s electricity generation. This would not amount to a wholesale nationalisation of the sector, which could be up to a staggering £185bn, but would still represent an extraordinary, and extraordinarily expensive, shift in the industry.

In reality, Labour’s plans on government ownership in the energy industry will probably lie somewhere between nationalising the networks and bringing the whole sector into government ownership, so the upfront cost will lie between a low of £55bn and a high of £185bn. Whatever the actual figure, we are talking substantial sums of cash.

So, would borrowing this large sum of cash be worth it? Government ownership of energy companies does, indeed, exist in many European countries – in the shape of firms such as Dong, EDF, ESB, Fortum, Engie, RWE and Vatenfall – and some of these companies already own parts of the UK electricity system. Would it therefore be sensible to spend Tens of Billions replicating the energy ownership structures of other European countries?

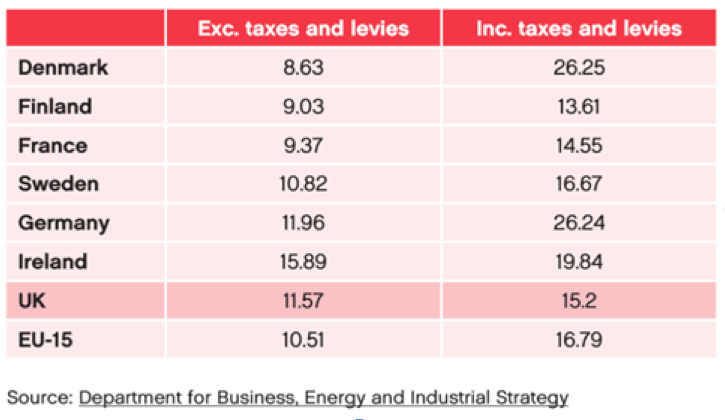

The evidence suggests not. There appears to be no evidence that state ownership in the energy sector would reduce the prices paid by residential customers. In fact, in Germany and Ireland – where there is significant government ownership in the energy sector – residential consumers pay much higher prices than in the UK, both before and after taxes. Moreover, international evidence suggests that privately-run energy assets are more efficient than those under government ownership. For example, on a cost-per-customer basis, privately owned electricity distributors in Australia operate their assets between 15 to 33 per cent cheaper compared to the equivalent publicly owned assets (which, incidentally, is much higher than the current returns for investors in UK energy networks).

International electricity prices for medium domestic consumers (Jan to Jun 2017)

This is not to say that there are no problems in the UK’s energy market. There certainly are.

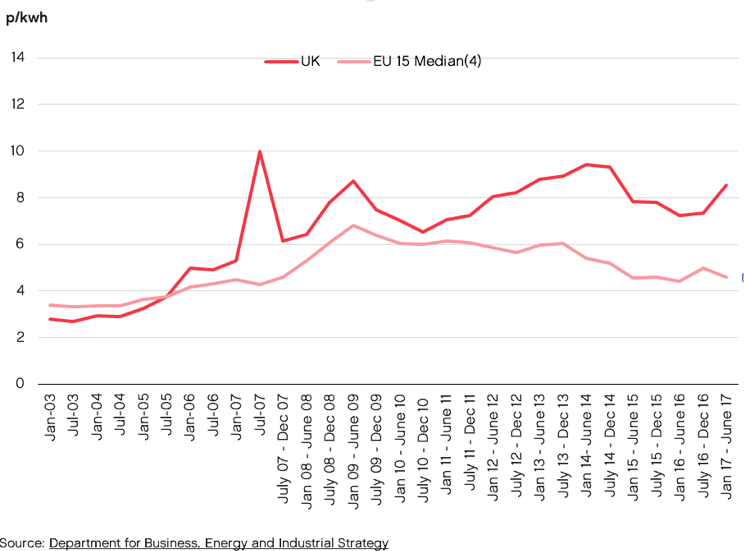

For example, while domestic households receive electricity prices that are around the EU average, the same cannot be said of industrial electricity prices, which are estimated to be some of the highest in Europe. Some of this can be attributed to unilateral green levies such as the Carbon Price Floor (CPF), but there are other reasons, too.

UK Vs EU industrial electricity prices excluding taxes (2003 to 2017) [large users]

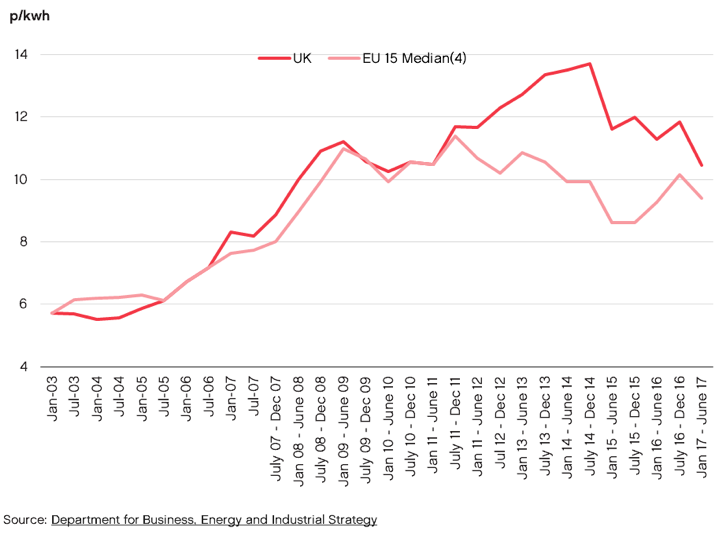

UK vs EU domestic electricity prices excluding taxes (2003 to 2017) [large users]

When you look at electricity prices exclusive of taxes, which strips out the impact of measures such as the CPF, it is clear that UK prices were competitive in the early 2000s. At this stage, the UK energy market was liberalised and faced little government intervention. Since then, however, the UK’s industrial electricity prices and, to some extent domestic electricity prices, have become less competitive. But this has corresponded with increased state intervention in the energy market, not further liberalisation.

This has been confirmed by a recent government-commissioned review into the costs of energy in the UK. It concluded that the cost of energy is significantly higher than it needs to be to meet the government’s objectives of ensuring energy security and hitting climate change targets. According to the report’s author, Professor Dieter Helm, this has arisen from the state moving away from mainly market-determined investments towards a situation in which all new electricity investments are chosen through technology-specific contracts.

Nationalisation of the sector is clearly no solution to this. Not only would the borrowing requirement be huge, it would simply further increase state intervention and squeeze out the remaining market mechanisms in place, leading to even worse outcomes for customers and taxpayers. Labour’s plans must be resisted.

But it’s no good in just resisting their plans. A better alternative has to be pursued. The most sustainable way of fixing the UK’s energy industry would be to promote competition in the energy retail market, bear down on the cost of environmental levies and re-introduce market mechanisms on the generation side of the market. This should be the focus of the government when it comes to the energy sector.