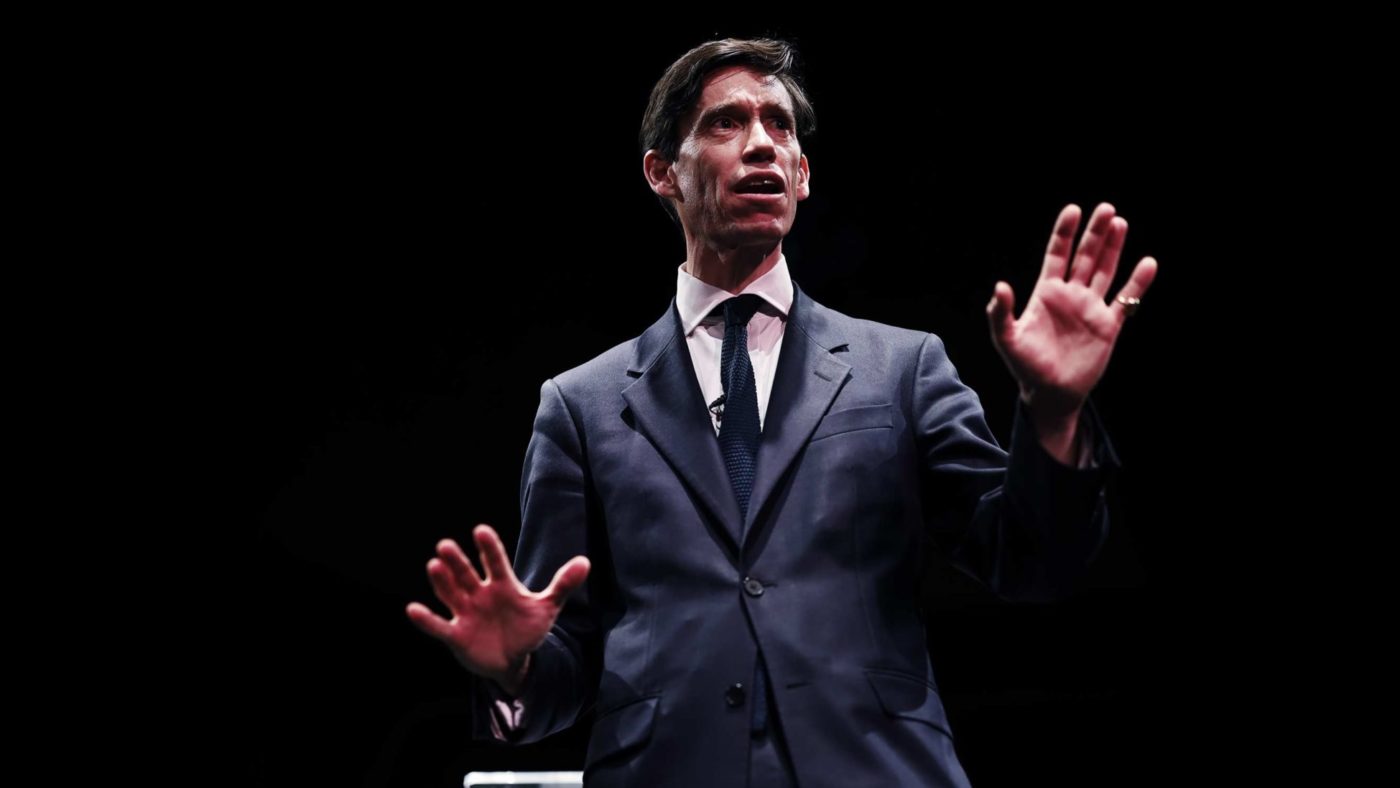

Rory Stewart is the modern day spiritual preacher for the secular class. He talks of “love,” of “issues” that only the enlightened have seen, and calls for people to “come together” in the “centre”. The secular class think they’re seeing something new because they don’t go to church, but they’re getting hoodwinked.

Stewart has called for citizens’ assemblies on Brexit — ignoring that we already had a much larger citizens’ assembly in June 2016 — subsidies for farmers after the government has tied them in red tape, social housing after barring new developments from being built by the private sector, tariffs and trade wars to ‘protect’ the producer at the expense of the consumer, and conscripting young Britons into a compulsory citizenship service.

It’s that last one that has really grated my gears. Claire Foges writing in The Times claims that Stewart is a man ‘who eschews jargon and sophistry’ but who wants national service to create a ‘collective endeavour for all young people, a mixing of tribes, a rite of passage into deeper patriotism.’

Sorry, but that is quite obviously jargon. Of course, Rory actually is someone who deals in rhetoric when it suits. When asked by LGBT+ Conservatives about their policies on the community, Boris Johnson, Sajid Javid and Michael Gove came back with detailed proposals; Rory came back saying his policies for the LGBT+ community ‘will be listening and love.’ His response on Brexit? Love.

For young people Stewart prescribes a universal, compulsory, National Citizen Service for all 16-year-olds for four weeks. He intends to use these weeks to somehow fix societal divisions, develop confidence, address mental health, and bring communities together. There are conceptual as well as practical issues with what Rory wants.

Rory has said he will do this on the day he becomes prime minister, seemingly ignoring the parliamentary process and democratic scrutiny he wants in other areas.

Four weeks on a budget Butlins is not going to be a magic fix. We can’t seem to fix potholes in Lincolnshire or knife crime in London, but somehow a few weeks of forced fun will redress the class divisions and geographic splits endemic in British society.

Fundamentally, there is a cost to forced labour — a monetary cost. Earlier this decade one of the few states still with large-scale conscription, Iran, started to charge people who wanted to avoid the service. People were willing to pay to avoid conscription at a higher value than the government placed on having conscripts. Conscription was a loss to the individual higher than the gain to the government. It was (and is) economically irrational with a broad cost of forcing everyone to serve borne by taxpayers.

There is a cost to the individual too, who cannot pursue what they would want to at the time of their choosing. Whether that’s a summer job, holidaying with mates, starting a side hustle, or running something beyond the wit of Whitehall. There is also the cost of forcing those to volunteer who would not voluntarily serve on present terms.

Usually, volunteering lets people work out where in an economy they are best suited — Koch and Birchenall found that volunteers left more high-income earners in the civilian sectors, and so a large base of taxpayers to pay for the services in the first place. Take these people out and put them in this cuddly version of the draft, and the pool to fund it goes down. More importantly, all of that money doesn’t go on things like nurses and doctors and teaching and roads and yes, Brexit.

Importantly too, you might want people at things that actually want to be there. A famous exchange between General Westmoreland and Milton Friedman during the US’s period of conscription captured this best. When Nixon mooted the idea of bringing it to an end, Westmoreland shot back saying that he did not want to command an army of mercenaries. Friedman asked whether he’d rather an army of slaves.

The argument is eyebrow-raising — but true. We’re all mercenaries when we aren’t coerced. We have mercenary footballers, and mercenary generals, and mercenary professors. Given the level of national fervour for the NHS, and to the likes of Manchester United and Liverpool FC, there’s little logic to say that you need conscription to build loyalty. If anything, forcing young people to “serve” their country through national service could endear even more anger and hatred against a Union already embattled.

This is also infantilising people who need to grow up. Sixteen-year-olds are on the verge of adulthood. They need to be trusted to make decisions over their own lives.

There is no moral case for a man in Whitehall deciding what is good for the character of someone hundreds of miles away. There is no right for Mr Stewart and Ms Foges to decide that society is endangered by the ‘silliness’ of things like Love Island. A great many people find Westminster a silly place filled with egos too. If you ask them which they’d like to keep, the chattering classes might not like the answer.

There’s the liberal case that knows that community is not that wiley thing of yore. We are no more islands in a sea of misery than any generation that has come before. Social media is mostly neutral for kids’ happiness, as Amy Orben’s research at Oxford University found. Online does not mean detached. In many cases it provides a way out of a harsher physical world. Mats Steen is the person I think of most often about this. Born with Duchenne muscular dystrophy he found friendship online with hundreds of people, where in a traditional community he’d have been left behind. When he died his parents discovered a network they didn’t know that cared about — and yes, loved — their son. All voluntary, from all around the world, and all stemming from playing a game that our betters think beneath them.

There’s the Conservative case. This leadership battle has shown the ideological fault lines at the heart of the Tory Party. I’m happy to say that I stand with those who support the free market. I have an intellectual inheritance that goes beyond populism or patricianism. As Margaret Thatcher put it: “a man’s right to work as he will to spend what he earns to own property to have the State as servant and not as master — these are the British inheritance.”

Finally, there’s the argument from love. It cannot be coerced and it cannot be created from on high. It has to be earned. If Rory Stewart is really serious about tackling complex issues, he’ll stop offering simplistic solutions — and the chattering classes will have to stop buying into them, listen, and learn.