Last week, the United States Senate committed to spending more than $50bn on US semiconductor production. It was a long time coming, as the bill had been stuck in Congress for almost a year. Some claim that the chip shortage has started to ease as high inflation, China’s zero-Covid policy and the Ukraine conflict have combined to slash global demand. But the problem has not gone away. Now, as the US looks to get into the semiconductor business, we could see ramifications that reach far beyond manufacturing supply chains.

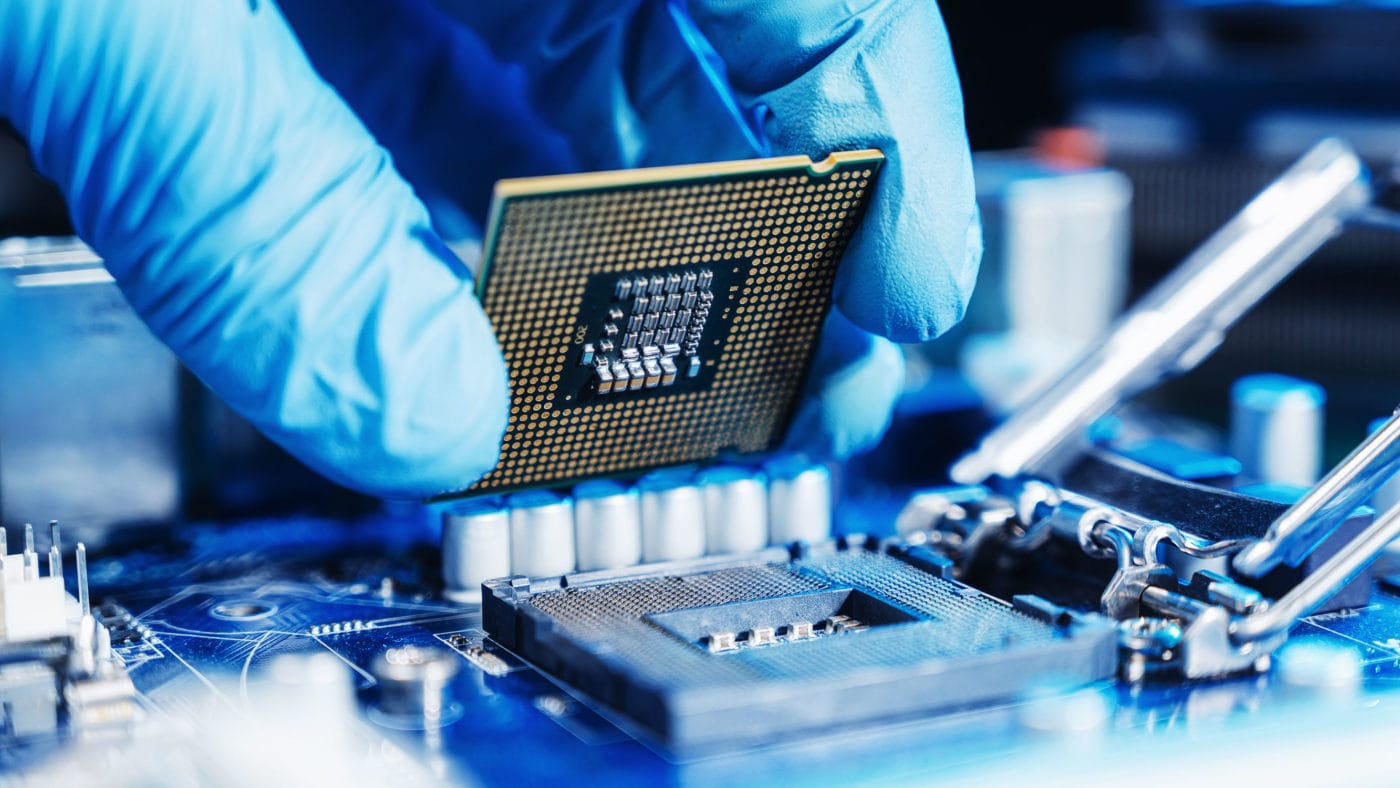

Kick-started by the pandemic, the shortfall of semiconductors, primarily produced in China, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, India and Germany, has played havoc with the global economy, slowing down the production of everything from smart fridges to smart missiles. Today, almost every complex piece of technology relies on a semiconductor: they are in our computers, our phones, and even our cars. The modern household is built on semiconductors, and so is a great deal of complex military machinery.

Supplies of semiconductors have historically been relatively reliable, but the ongoing disruption is pushing governments on both sides of the Atlantic to produce chips closer to home. If nations are unable to access semiconductor chips, whole commercial sectors could breakdown, and military and other critical infrastructure is left vulnerable.

A dearth of new chips will mean no new cars. It will also make it more difficult to update critical military systems and assets, leaving countries open to cyber-attacks. Leaders are now waking up to the fact that relying on global supply chains to supply the foundations of their economy is not a fool-proof plan. This is not just happening with chips. Concerns around global energy supplies are seeing governments invest in local supply sources, to ensure they can keep the lights on during the winter crunch. The geopolitical crisis in Europe is also threatening global food supplies, with many countries now looking for domestic alternatives.

These trends have led some commentators to predict the end of globalisation, but these pronouncements seem overblown. The global economy is not going to shrink overnight, and while a superpower like the US can afford to invest billions to create domestic industries, few other nations have that option. Instead, what the semiconductor crisis highlights is how easy it is for the world to be lulled into a false sense of security when facing a new frontier risk, such as a global pandemic. These dangers, often deemed to be highly improbable, are warned about while governments and businesses ignore the alarm bells, choosing instead to dedicate resources to more tangible short-term priorities. But then a frontier risk, such as the semi-conductor shortage, hits home and governments overreact, investing billions to shield themselves from a problem they had long disregarded. It is a familiar pattern, seen throughout history.

Policymakers should learn better lessons from the semiconductor crisis than just the need for more secure supply chains. There are many other frontier risks that governments should be looking to prevent, from cyber attacks, the risks associated with AI development, human enhancement, as well as critical food and water shortages and extreme weather events. Governments and businesses are reactive entities, but horizon scanning is a vital measure if we want to ensure that we are not caught off guard by crises. To prevent a future pandemic or a superconductor crisis, we will need to pinpoint potential weak spots and boost resilience – before a crisis hits. Public entities need to do more to create and empower departments to think about these issues, and give them the funding they need.

As our world becomes increasingly interdependent and interconnected, we need to create all-weather strategies and frameworks that minimise conflict while encouraging healthy competition and a more sustainable, secure, peaceful and prosperous global order. The framework need to be sustainable, robust and rooted in Multi-Sum Security – security in a globalised world can no longer be thought of as a zero-sum game involving states alone. This, in addition to building national resilience, is the most certain way to mitigate future unforeseen frontier risks of disruptions, which will be inevitable. No one truly believes in the dangers of frontier risks, until they are at our doorstep. The pandemic was one wake up call, but this chip crisis is another, how many do we need?

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.