“The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.” So famously observed John Maynard Keynes in 1936, in the conclusion of his opus The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Keynes proved prophetic, at least in his own case. “Keynesianism” as a doctrine came into its own during the 1970s, long after the man himself had disappeared; President Nixon, who declared, “I am now a Keynesian in economics,” probably had read little of the economist’s work.

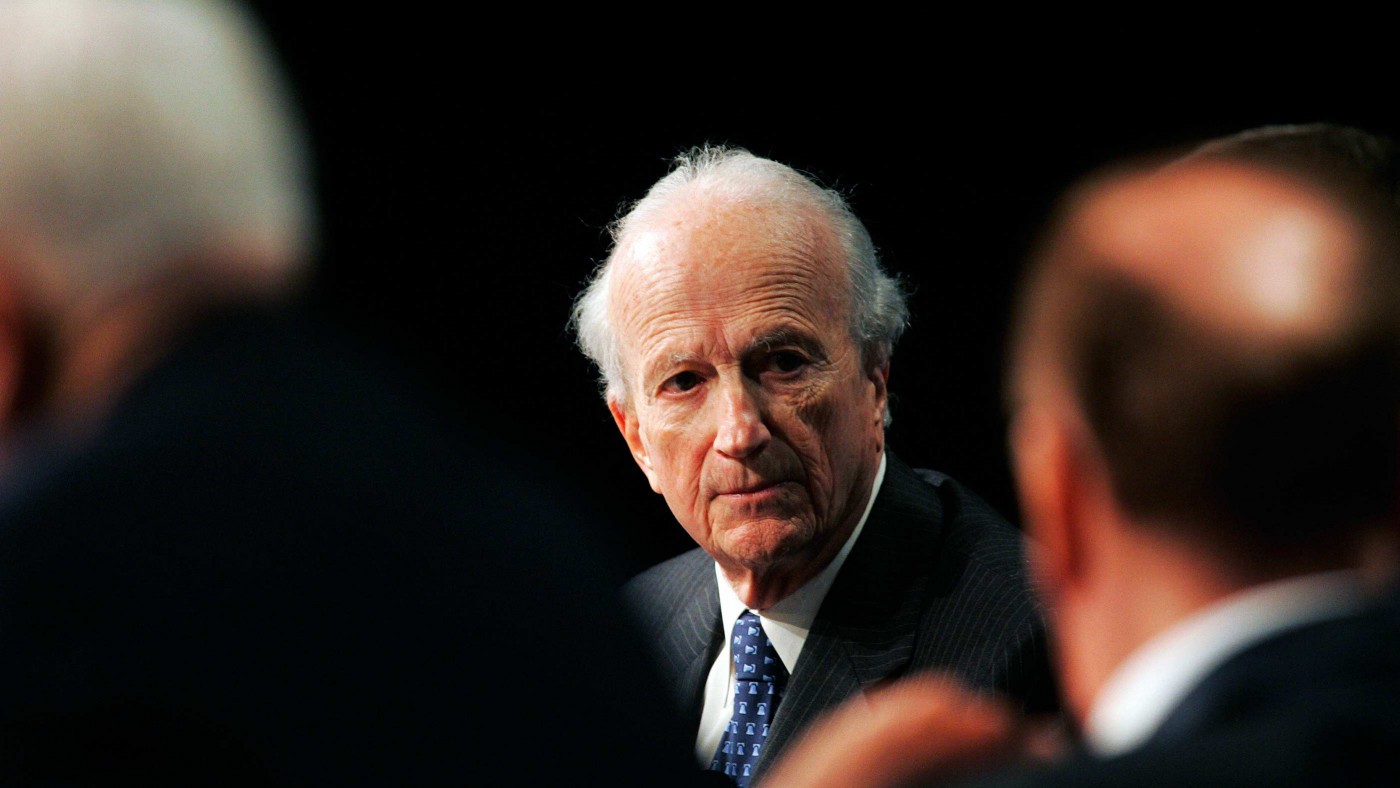

Keynes’s aphorism has been reliable when applied to free-market economists, too—and some of them haven’t had to wait for posthumous vindication. Friedrich Hayek became influential while he was still alive, helping inspire the economic policies of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. “This is because I lived too long,” quipped Hayek. Milton Friedman stuck around long enough to see the end of hyperinflation, thanks to the application of his monetary theories. A third Nobel Prize–winning University of Chicago economist, Gary S. Becker, who died last April, may have been less famous during his lifetime than Hayek and Friedman, but his ideas lie behind some of the most striking policy innovations of the last few decades.

The politicians implementing those policies probably hadn’t worked their way through The Economic Approach to Human Behavior, Human Capital, A Treatise on the Family, or other dense Becker studies. But they could easily have become acquainted with his thinking through his clearly argued Businessweek columns, collected in the 1998 book The Economics of Life: From Baseball to Affirmative Action to Immigration, How Real-World Issues Affect Our Everyday Life, or the popular blog he cowrote for several years with Judge Richard Posner, the highlights of which appeared in book form as Uncommon Sense in 2009.

And some of Becker’s Chicago disciples turned his theories into recent bestsellers. Just about everyone has heard of Freakonomics, the wildly successful book by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner that popularized Becker’s view that criminals are like entrepreneurs, responding to market incentives. In many ways, then, Becker’s star is ascending—and that’s a good thing for economics as a discipline and, more broadly, for our public policy debate.

Becker was astonishingly ambitious, bringing market-based thinking and solutions into fields—from crime to job discrimination to medicine to traffic flows—where no economist had gone before. Becker dubbed his approach “rational action theory.” In economics, as in other sciences, theory is necessary. It will offer an imperfect description of the real world, yes, but without one, the world can’t be seen at all. Indeed, all major breakthroughs in economics have been built on new theories, Becker’s included, though he agreed that no theory was final.

Rational action theory holds that all human beings, in all civilizations, act “as if” they are rational. For Becker, this meant that they acted as if they sought to maximize their profit in a market. “Nobody ever claimed that people were perfectly rational all the time,” Becker told me in a 2009 conversation. “People make mistakes. They may get under the sway of emotions. My theory has recognized that from the beginning. What I have argued, however, is that when you put the collection of individuals together in markets, the markets perform better than any alternative that has ever been devised.”

We’re entrepreneurs in all walks of life, Becker believed, responding to incentives and behaving, more often than not, rationally. In his work on the family, to take a controversial example, Becker showed how parents tended to choose the number of children they had in order to maximize the overall welfare of the family, as if it were an economic firm. Parents invest in their children’s education as well, seeking to boost their offspring’s “human capital,” an investment that they hope will bring positive returns. Becker didn’t invent the concept of human capital—the cognitive habits, know-how, creativity, and other mental attributes that generate economic wealth in a modern economy—but he was the first economist to use it systematically, as a basis for his reasoning and policy arguments. He was keenly aware that we live in a time—in the developed world, anyway—when human capital has superseded physical capital, and he invited his fellow economists to adapt to this new reality.

Becker’s ideas—in many cases, unacknowledged—have also transformed the debate over another urban plague: traffic congestion. The planner’s old answer to congestion was to widen streets, add traffic lights, and build new tunnels and overpasses, all in the hope of making traffic more fluid. To no avail: the expensive public works actually worsened congestion by encouraging more drivers to take cars to the city, overwhelming the new infrastructure. Becker instead applied a strict market calculus to urban traffic. Any commuter or visitor who chose to enter a city center with his own car or truck, Becker explained, had an interest in doing so.

The individual driver’s choice looks rational to him; he thinks that he will gain in comfort, access, and time. His choice, though, exacts a cost on other drivers in the form of greater congestion, producing what economists call a negative externality; he, too, becomes a victim of the congestion he helped cause. At the end of the day, all the drivers lose. “Time spent in traffic is an inefficient ‘price’ since it wastes the time of drivers without providing benefits to anyone else,” argued Becker. He estimated congestion’s cost to be $50 billion a year in the U.S.—a massive tax on time.

A market solution to the problem, easier to apply than any massive new road-construction project or bureaucratic regulation, would encourage drivers to make more rational choices by requiring payment for vehicle access to downtown areas and city centers. A version of such “congestion pricing,” as the idea has come to be known, was implemented in London several years ago by then-mayor Ken Livingstone; road congestion in London dropped by 20 percent, as many commuters opted for cheaper public transportation, leaving their cars at home. Former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg tried to impose a similar entry toll in Manhattan during the mid-2000s, but the initiative, opposed by neighborhood officials and downtown shopkeepers, was defeated.

Becker felt that Bloomberg had failed to explain how traffic congestion represented an economic loss for all New Yorkers. He wasn’t fully satisfied with the London system, either. Traffic congestion varies by the hour and day, he noted, so, as with airline tickets, the price of driving into the city should depend on the time—something the London plan, which had a uniform rate, didn’t take into account. But congestion pricing of some kind will be adopted by more cities in the future: mayors of large cities these days, even if they have never heard of Gary Becker, know that spending a ton of money on new arteries or underpasses to ease traffic is likely to be ineffective—a victory for Becker’s market-based thinking.

Becker not only came up with market-based solutions to public problems; he also debunked government efforts to use extensive regulations and spending to address those problems. This was a critical task, since the regulate-and-spend nanny-state approach, which denies the rationality of individuals and their capacity to take care of themselves, is seductive to many politicians and even to the public, in part because its unintended negative consequences, both moral and fiscal, aren’t always evident at first.

Becker viewed the Bloomberg administration’s 2006 ban on trans fats in restaurants as a classic example of overreaching regulation. The administration presumed that New Yorkers were too ignorant to make decisions in their own health interests. But were they? Yes, the evidence suggested that trans fats contributed to heart disease—though the degree of harm remained unclear. But before the ban, half of the city’s restaurants didn’t use trans fats, so health-conscious consumers could already easily avoid them if they wished. Further, the ban likely raised the cost of eating out in the city.

Could such a price increase lead some New Yorkers to eat more at home—and perhaps eat more trans fats, too? Policymakers ignored such a possibility. Some customers, of course, may really love trans fats and want to consume them, even knowing that they could have bad health effects in the future. Defenders of the ban would say that making that choice could increase the incidence of heart disease in the city, which would burden Medicare and hence the taxpayer—a negative externality. If this were true, though, why not just let insurers require individuals who want to eat unhealthily to pay higher premiums? Why should the government impose a new regulation that diminishes freedom?

Public policies that curb personal liberty, Becker argued, too often are based on insufficient data; politicians regularly put them into effect without considering all their potential consequences or exploring alternatives. And such prohibitions are politically hard to remove, he added, meaning that the sphere of freedom continues to shrink.

Gary Becker never ran for political office; he was seeking the truth, which he did tirelessly until his death, at age 85.