The spending plans in Labour’s manifesto may be grabbing the headlines — but it is perhaps their underlying anti-capitalist ideology that should give us the most discomfort.

Labour proclaim that current corporate Britain has been “corrupted by a culture in which the long-term health of a company is sacrificed for a quick buck for a few” which has led to asset-stripping and redundancies.

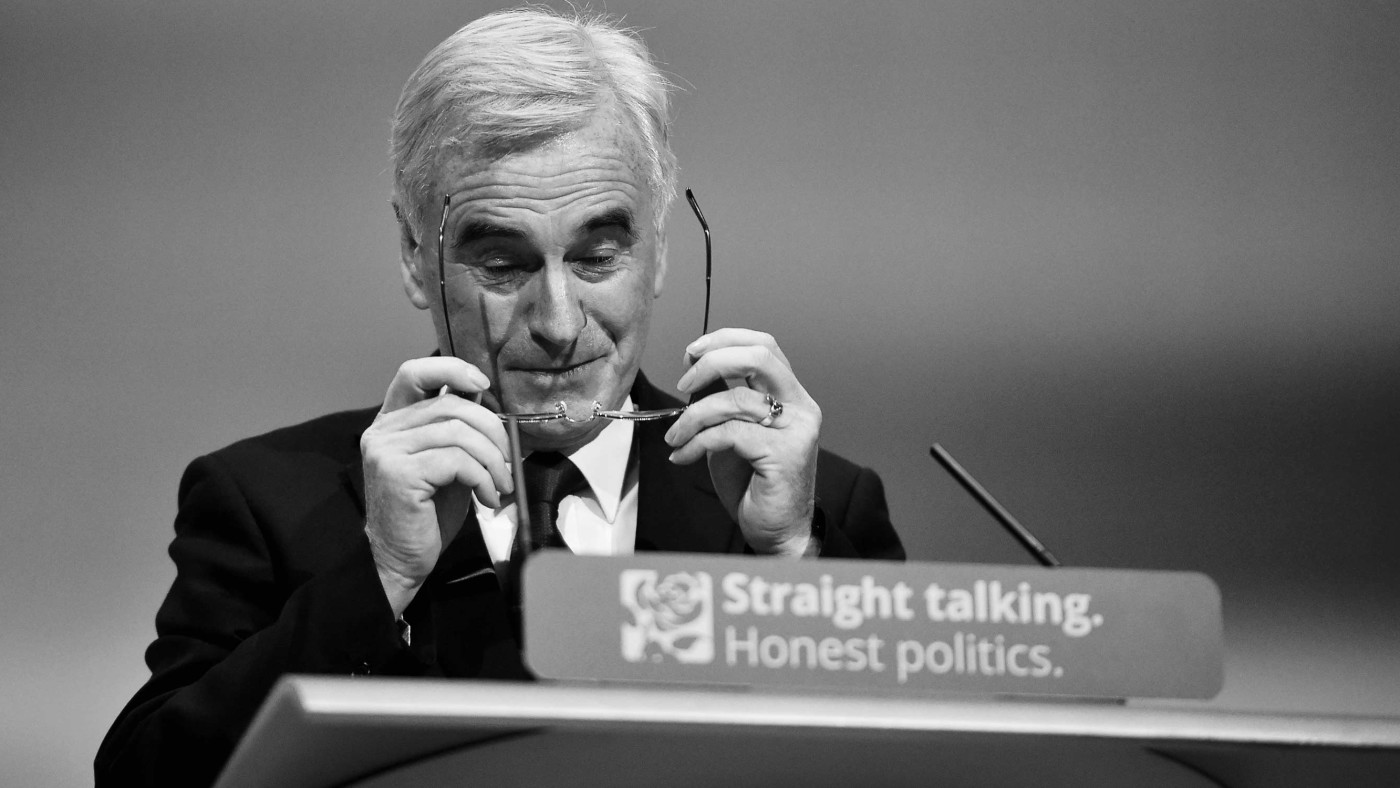

The solution, according to shadow chancellor John McDonnell, is an amendment to the Companies Act, to require “companies to prioritise long-term growth while strengthening protections for stakeholders, including smaller suppliers and pension funds.” It would also “require one third of boards to be reserved for elected worker-directors and give them more control over executive pay”/ They argue that “when those who depend on a company have a say in running it, that company generally does better and lasts longer.”

This is an attack on the principle of shareholder ownership and the ability to control our own money. If enacted, it would constitute a serious restriction of shareholder control over their own property and would contribute to the capital flight predicted if Mr Corbyn enters Number 10.

The Liberal Democrats’ manifesto released yesterday takes a similar approach, committing to change the fiduciary duty and company purpose to include “considerations such as employee welfare, environmental standards, community benefit and ethical practice, alongside benefit to shareholders, and that they report formally on the wider impact of the business on society and the environment”.

The Companies Act 2006 imposes the requirement to have some regard for social responsibilities, which rightly drew much criticism at the time. But even these responsibilities are largely within the context of promoting shareholder benefit. Labour’s rewriting of the act would impose broader responsibilities at the same level of importance as providing for shareholders. They would also create a “Companies Commission” to enforce broader social responsibilities on business, presumably meaning any business that fails to comply could be punished or shut down.

The economy works much better when these restrictions are not put onto businesses. Not only this but, as Milton Friedman pointed out in his seminal defence of shareholder capitalism from 1970, ‘the discussions of the “social responsibilities of business” are notable for their analytical looseness and lack rigour.’

Firstly, individuals are moral agents, not groups. Thus any moral responsibility is that of the individuals. It is wrong to insist that directors possess some sort of social responsibility in their role in corporations. Directors are the employees of the shareholders. As Friedman explains, “their responsibility is to conduct business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible” while conforming to their basic rules of society embodied in law and ethical custom. Directors are responsible to shareholders who then set the aims of the corporation.

Secondly, for directors to deviate from the plan of making as much money as possible they must divert money away from one or more of the three groups that they deal with. These are their employers (shareholders), those to whom they sell (consumers) and those from whom they buy (both suppliers and employees in the form of goods or labour). In order to contribute to this loosely defined social good, they must divert some money away from these groups either by reducing profit, selling a more expensive or worse good, or buying less/paying less to their suppliers. As a result, these directors are making arbitrary decisions at the expense of these other groups, or as Friedman describes, taxing them.

This is not the job of directors but that of the government which is accountable to the electorate. Such a change to the responsibilities of directors actually makes them less accountable to the shareholders who have taken the risk by investing their capital in the business. .

Thirdly, shareholders can set the objectives for their firms to be something other than simply profit maximising. In fact, many do, whether it is ocean clean-up projects to attempting to reduce deaths caused by woodstoves. However, to force firms to do this is begs arguments of economic freedom versus a planned economy.

Labour criticises the short-termism that is stifling businesses. But if there is shareholder myopia then it is the shareholders themselves who stand to lose out. If there is myopia by directors then enacting legislation that would reduce the accountability of directors to their shareholders will make the situation even worse. You can just imagine businesses going bust due to some woke CEO deciding to do some ‘socially responsible’ vanity stunt. Just see the struggle faced by Irn-Bru following the change in formula to cut sugar.

Corporations are incentivised to engage with stakeholders as it is in their best interest. Nurturing good relationships with suppliers and employees is crucial to the long term health of the business. Indeed it is also important to remember that shareholder activism is the predominant and best method of restricting excessive corporate pay.

Individuals have the freedom to be socially responsible if they choose. Many people across the country subscribe to ethical frameworks, both religious and secular, and use these to guide their own personal choices. The imposition of a poorly defined ethical framework by the state onto individuals capable of their own moral judgments is just as much an abuse of religious freedom as it is an economic one.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.