Today marks 200 years since the birth of Karl Marx.

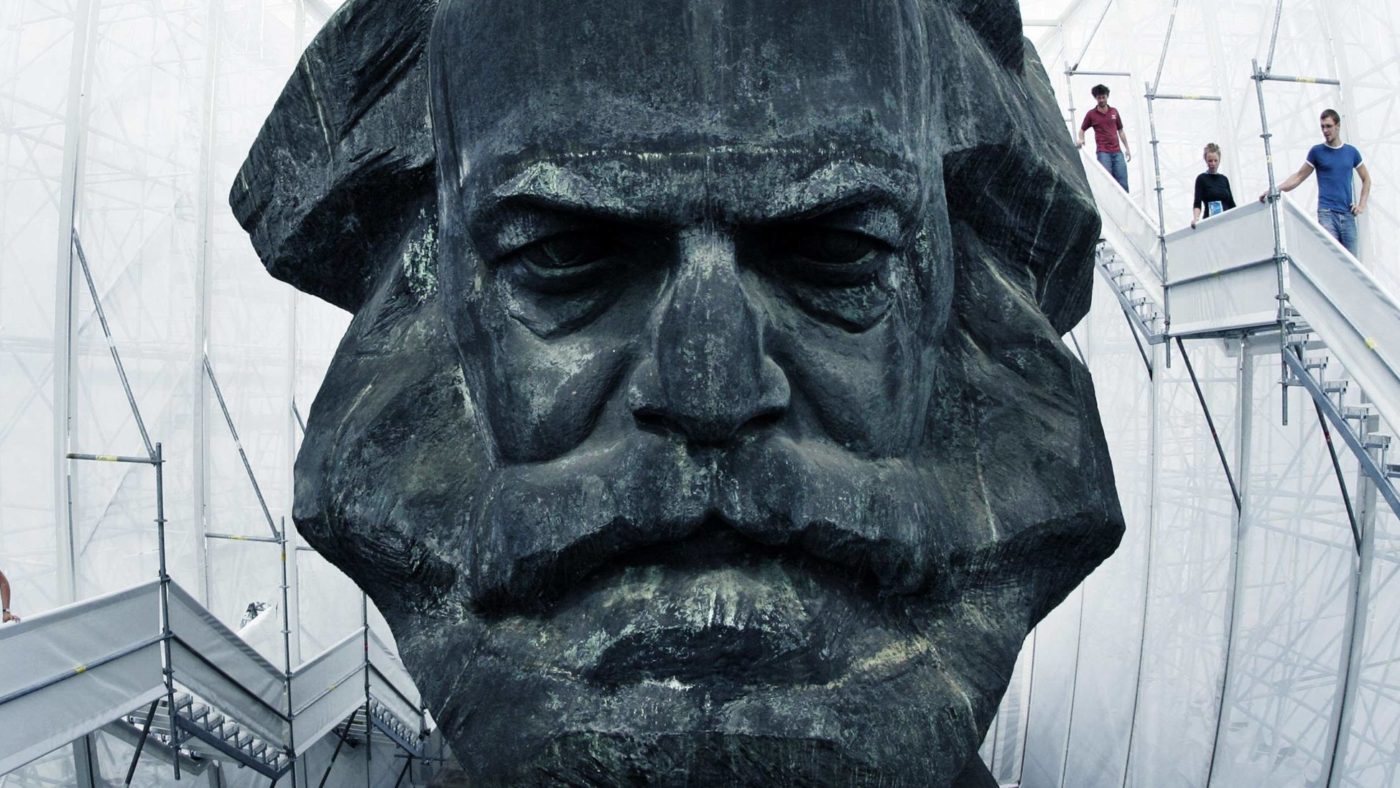

This milestone in the history of bad ideas is being commemorated with a predictable flurry of columns on why the German thinker was right, conferences at which like-minded academics will be nodding along to overwrought critiques of “neoliberalism”, and the eyebrow-raising spectacle of Jean-Claude Juncker speaking at the unveiling of a Chinese-funded statute of Marx in his hometown of Trier.

In Britain, Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell is appearing at a “Marx 200” event. It will also be a notable date for Jeremy Corbyn, as well as hangers-on like Marxist spin doctor Seumas Milne and Communist Party of Britain member turned Labour adviser Andrew Murray.

Today, then, is a reminder – not that one was needed – of the dangerous and disproven ideas that hold sway at the top of the Labour Party.

I don’t have space here to go into all the ways in which Marx was wrong – others have done that on CapX in far more detail. And besides, if you really want to understand contemporary British politics, there is more to be gained from spending Marx’s birthday considering who won’t be dusting off their copies of Das Kapital than who will. While Corbyn and McDonnell are devoted Marxists, the overwhelming majority of their devotees couldn’t care less about a long-dead German writer.

This may seem an obvious point. But it is one that many of Corbyn’s political opponents have missed, falling into the trap of thinking they are fighting a pitched battle against an army of doctrinaire leftists.

What makes Corbyn and McDonnell so dangerous is the way in which they have tapped into far less radical sentiment. In the eyes of millions, Labour is the party of well-funded public services and a fairer Britain. For far too many of those voters, it is also the party with a monopoly on good intentions.

It may be true that the Marxist governments Corbyn and McDonnell have spent their careers defending always end in failure. That should be pointed out at every possible opportunity. That said, history lessons are not a recipe for electoral success.

Politics is often described as a battle of ideas. That isn’t quite right. In truth, it is a battle of ideas put into practice. Which is why the fight against Corbyn has to be more than a fight against historical ignorance.

In the eyes of voters, Corbynism isn’t a theory that can be disproven. It is a hazy vision that will look alluring until a better alternative comes along.

In this contest of different visions for the country, Labour has some big advantages. Foremost among them is austerity fatigue, which puts them several steps ahead of the Conservatives on debates about public services. More money for schools, hospitals and the police is a simple and appealing battle cry. Explaining that money is only part of the problem and restating the case for responsible fiscal policy are a lot harder.

For the Conservatives, their biggest strength is also their biggest weakness: incumbency.

The party in government must shoulder the blame for anything that goes wrong. Yet it also has the chance to fix the problems that have voters so frustrated and strike decisive blows not in the battle of ideas, but the battle of ideas put into practice.

The really frustrating thing is that there are a lot of tried and tested ways to fix the things voters care about. On the cost of living, housing, economic growth and public services, it is Conservative sheepishness, a field full of sacred cows and a hypersensitive Tory base that make things more difficult than they could be.

Tories frustrated by Jeremy Corbyn’s popularity among young voters need a history lesson of their own. It is one that you can learn from more or less any country at any point in history. It is that people just aren’t that ideological. Their priorities – safety, prosperity and happiness for themselves and their families – are universal. In a democracy, the adherents of an ideology that doesn’t deliver on those fronts won’t hold on to power for long.

Marx thought capitalism would collapse under the weight of its own contradictions. In fact, it has done the opposite. The mix of markets and liberal democracy has moderated itself and endured by delivering material results for billions of people.

As Marx turns 200, Britain is at an ideological crossroads. The path it chooses will be determined first and foremost by what works.

This article is taken from CapX’s Weekly Briefing email. Sign up here.