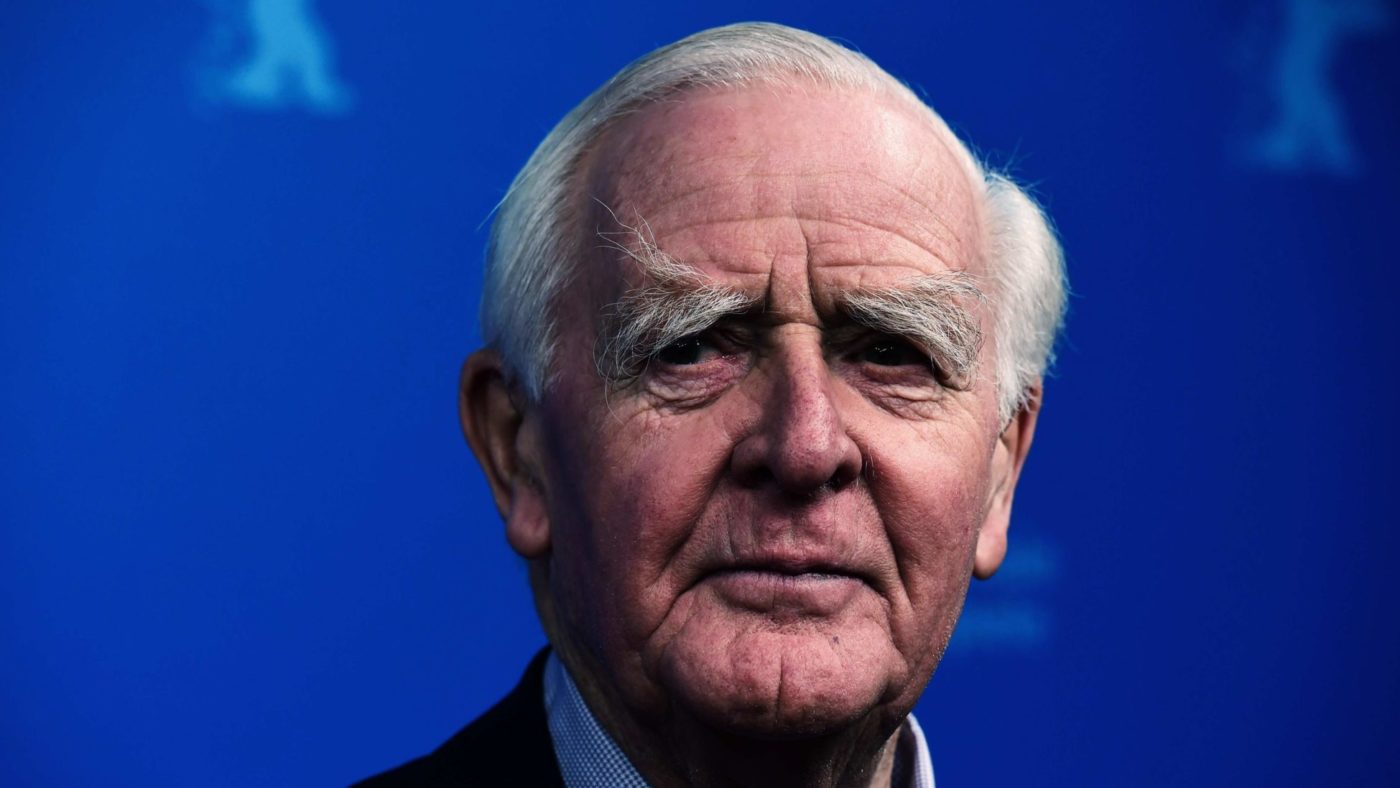

Poor David Cornwell. He is the country’s most famous (real) spy, a veteran of MI5 and MI6, who as the Berlin Wall was being built, was busy tapping up Soviet diplomats in Bonn, and yet among the UK’s commentariat he has developed a latter-day reputation as some kind of apologist for communism.

On Monday, Alex Massie was at it in these pages with his meditation on the British left’s moral relativism towards Soviet Russia: “This is a view inculcated and encouraged, it must be said, by the novels of John Le Carré (Cornwell’s pen name), in which the aims of policy are typically ignored in favour of a concentration on the means.”

This seems a bit harsh, not least because Massie was bought to this conclusion by his reading of Ben MacIntyre’s The Spy and the Traitor, a book which Le Carré plugged as “The best true spy story I have ever read.”

Massie’s criticism joins that of the Spectator’s Toby Young, “his novels gave succour to the enemy,” and Rod Liddle, “(his) characters are ciphers for the author’s fashionably baleful view of the world, in which the cynicism of the Soviet Union is matched by the cynicism of the West.”

For someone who lost his job after being exposed by Kim Philby (an actual Communist double agent), this does seem unfair to Le Carré/Cornwell, who I would argue has claim to be our greatest living writer.

The hostile view of Le Carré is as old as his books. In his autobiography The Pigeon Tunnel, he recounts being berated by an angry former colleague for presenting a warts-and-all view of the Service when they have no recourse to answer back. The colleague’s ire was raised by one of Le Carré’s early novels The Looking Glass War, an undoubtedly bleak telling of a wireless operator’s mission behind enemy lines.

But Le Carré’s critics should credit his audience with more nuance. Far from being a recruiting sergeant for the Soviets, his books have tended to do the opposite. The author notes that a vast proportion of his fan mail is from wannabe spies wondering how to get that tap on the shoulder from MI6.

When Alec Leamas in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold derides the cynicism of his profession: “What do you think spies are: priests, saints, martyrs? They’re a squalid procession of vain fools, traitors, too, yes; pansies, sadists and drunkards, people who play cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten lives,” apparently many of us are thinking – where do I sign up?

Arguably it is this nuance which makes Le Carré’s characters so attractive to the reader. One of Toby Young’s gripes against the author is how a certain type of person regards Le Carré as far more sophisticated than James Bond. Surely it is possible to enjoy both while understanding that for many readers it is at least easier to empathise with the drunk and the hen-pecked rather than the ruthless assassin of Ian Fleming’s novels.

It is also his characters’ fallibility which makes them so much more attractive than their Soviet counterparts in his novels. George Smiley knows that ultimately his spy service will triumph against Karla’s Moscow Centre because of, not in spite of his flawed civil servants. “Karla is a fanatic,” he says in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. “One day that lack of moderation will be Karla’s downfall.”

Given Le Carré’s first-hand experience of this fanaticism with Kim Philby, it also gives the lie to Liddle’s accusation in the Sunday Times a decade ago that the author had once considered defecting to the Soviet Union.

What Le Carré actually pointed out was merely another of the themes in his books which takes the reader closer to the experience of a contemporary spy: the almost Stockholm Syndrome secret agents can develop with their opposition.

This is an idea he explores in particular in his novel Our Game where MI6 admit they expect a bit of wear and tear in their double agents working against the Soviets. In the book a double agent run by the Service develops a strong bond with a Russian general which leads him into the world of Chechen separatism

This aspect of Our Game is also striking in its focus on a part of the world which only a year later was leading the headlines when Russia staged the First Chechen War. Not only had Le Carré proven himself a diligent journalist by hanging out with Chechen mobsters in Moscow (generally feared at the time as the go-to hitmen for many of Moscow’s crime syndicates) to research the book, he also proved remarkably prescient about the direction post-Soviet Russia was taking.

A similar note is struck in his later novel Our Kind of Traitor, where Le Carré attacks the British governing class’s cosying up to Russian oligarchs long before kleptocracy, shell companies and Unexplained Wealth Orders drifted into contemporary debate.

With books focusing on such topics as establishment venality, the immorality of big pharma, how the old school tie isn’t probably the best way to run a clandestine service or how Israeli deterrence against the Palestinians has verged on the side of excessive, the only charge against Le Carré might be that he is a bit of a lefty.

However, a quick peruse of MI6’s website shows a marked emphasis on such cosy topics as “Wellbeing” and “Diversity is our strength” suggesting Le Carré’s views would be in good company if he was sitting in today’s Vauxhall Cross. John Le Carré/David Cornwell is not a left-wing zealot. For many of his readers, at the grand old age of 87, he remains a perfect spy.